In today’s world, visuals drive almost everything, from how a self-driving car spots a cyclist instead of a traffic cone, to how your phone unlocks the moment it recognizes your face. Behind these everyday wonders is a quiet revolution. A powerful movement is led by a special kind of deep learning model called Convolutional Neural Networks.

Convolutional Neural Networks are not just a smart software, it’s one of the biggest steps toward teaching machines to see the world as humans do. These networks are inspired by how our brains process images. They give computers the ability to “see,” analyze, and respond to visual information with impressive accuracy.

In this guide, we’ll break down the science and structure behind Convolutional Neural Networks and show how they power practical applications. By the end, you’ll see how this once complex concept has become the foundation of modern artificial intelligence — clear, practical, and deeply transformative.

The Science Behind Neural Vision

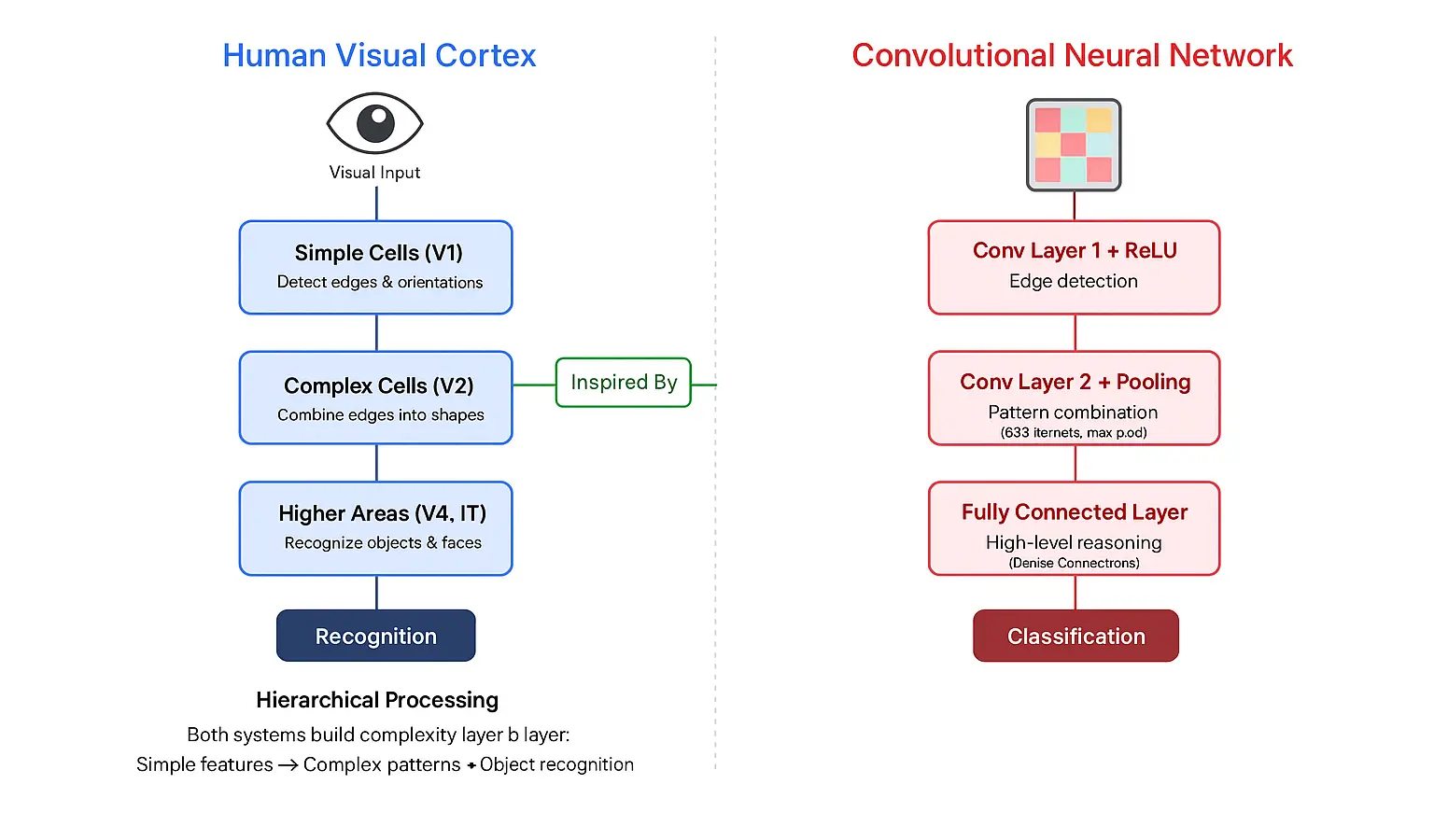

Our brain pulls off something incredible every second. When we look at a dog, our visual cortex doesn’t see the whole picture at once. It breaks the image into smaller steps—first spotting edges, then shapes, then textures—until it finally puts everything together and recognizes, “That’s a dog.”

Convolutional Neural Networks work in the same way. They copy this layered process using artificial neurons. This isn’t a coincidence—it’s deliberate biomimicry. Back in the 1960s, neuroscientists David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel made a significant discovery. They found that cells in the visual cortex respond to certain patterns. Some neurons fired when they saw vertical lines, others reacted to horizontal edges, and deeper layers responded to more complex shapes.

Computer scientists used this biological insight as inspiration and turned it into math. In a CNN, each layer acts like a stage of our brain’s visual system. The first layers detect simple features such as edges and corners. The middle layers combine those into shapes and textures. The deeper layers finally recognize complete objects and scenes—just like our brain does when we look at the world.

Hierarchical Feature Extraction

The real magic lies in a process called hierarchical feature extraction. A CNN doesn’t need to be told what a “wheel” looks like to recognize a car — it figures that out on its own. When you feed it thousands of car images, it automatically learns patterns, noticing that certain shapes, curves, and textures often appear together.

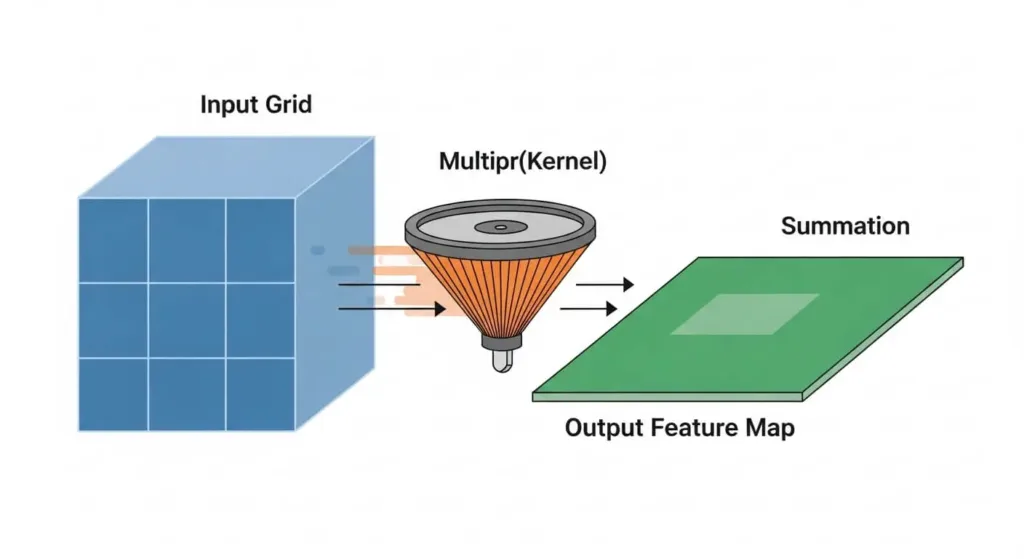

This learning happens through convolutions, which are simple mathematical operations — and that’s where the “convolutional” in CNN comes from. In this step, a small window called a filter or kernel slides across the image, scanning it for specific patterns. Think of it like having hundreds of mini-detectors, each one trained to spot a unique feature.

As the network goes deeper, it starts recognizing more complex patterns. The first layers pick up on basic edges and lines. Middle layers focus on textures like fur, glass, or metal. The deepest layers understand full concepts — like a “cat face” or a “steering wheel.”

This layered learning makes CNNs incredibly powerful for computer vision. They don’t just memorize pictures — they actually learn how to understand them. Just like your brain doesn’t store every single dog photo you’ve seen, a CNN learns what “dogness” means by finding the common features across many examples.

Convolutional Neural Networks Architecture Explained: Layers, Working, and Key Components

What makes Convolutional Neural Networks unique is its structure. It works like a step-by-step pipeline, where each stage processes the image and turns it into a simpler, more meaningful form. A standard CNN consists of three main layers. These are the Convolutional Layer, the Pooling Layer, and the Fully Connected Layer. Each layer plays a key role in understanding the image.

1. Convolution Layer

The Convolutional Layer is the heart of the CNN. Its job is to perform feature extraction by detecting local patterns in the input image.

Kernels and Filters: The Feature Detectors

The detection is done using a small matrix of numbers called a kernel (or filter). This kernel slides over the input image (or the output of a previous layer), performing a mathematical operation called convolution. This process generates an activation map or feature map.

For a grayscale image input I and a filter K (kernel), the output feature map S(i, j) is calculated as:

- Filters are essential because they contain the learned weights of the network. A single filter might learn to detect vertical edges, while another learns horizontal edges, and others learn complex textures.

- Stride determines how many pixels the filter shifts over the input matrix. A larger stride means a smaller output size.

- The resulting feature maps represent where these specific features were found in the input image.

2. Activation Functions

After the convolutional operation, the resulting feature map is passed through a non-linear activation function. This step is critical because it introduces non-linearity into the model, allowing the network to learn complex patterns and relationships beyond simple straight lines.

- ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit): This is the most common function in modern CNNs. It simply outputs the input directly if it is positive, and zero otherwise. Mathematically, f(x) = max(0, x). Its simplicity and effectiveness in mitigating the vanishing gradient problem have made it the industry standard.

- Sigmoid & Tanh: These older functions compress the input into a range (0 to 1 for Sigmoid, -1 to 1 for Tanh). They are useful in certain contexts. However, they are generally avoided in deep layers. This is due to the “vanishing gradient” problem, which slows down learning.

3. Pooling Layers

The Pooling Layer (or subsampling layer) serves two main purposes. The first is to reduce the spatial size of the representation. The second is to reduce the number of parameters and computation in the network. This reduction helps in controlling overfitting.

- Max Pooling: The most popular method. It takes a small region (e.g., 2×2) in the input feature map and simply outputs the maximum value from that region. This maintains the presence of the detected feature while discarding redundant spatial information.

- Average Pooling: Computes the average value of the small region. It is less common but sometimes used.

This reduction process makes the model more robust to variations in the position of the features. If a feature, such as a sharp edge, shifts slightly, Max Pooling will likely still capture it. This is because Max Pooling only cares about the highest activation value in that small window.

4. Fully Connected Layer & Softmax Output

After several cycles of convolution and pooling, the highly processed, two-dimensional feature maps must be converted into a one-dimensional vector. This vector is then fed into the Fully Connected Layer.

The Fully Connected Layer is essentially a standard, dense neural network. Every neuron in this layer is connected to every neuron in the previous layer. Its role is to use the high-level features learned by the earlier layers to perform the final classification based on the entire input.

The final layer uses the Softmax activation function. Softmax converts the output scores of the last layer into a probability distribution. For example, if the model is classifying images of cats and dogs:

- Input image: A picture of a Cat.

- Softmax Output: [Cat: 0.95, Dog: 0.04, Bird: 0.01]. The output clearly identifies the image as a cat with a 95% probability, completing the image recognition neural network task.

Training Convolutional Neural Networks: From Data Preparation to Model Accuracy

Building a CNN is just the start — the real challenge is teaching it to recognize images correctly. Training is where the magic happens. It turns a network with random weights into a smart image classifier through clean data preparation and precise mathematical optimization.

1. Dataset Preprocessing

Raw images are often messy — they vary in size, lighting, and format. Before we can train a model, we need to clean and standardize them.

Normalization helps by scaling pixel values to a fixed range, usually between 0 and 1, or -1 and 1. This makes it easier for the gradient descent algorithm to learn quickly and efficiently. Instead of working with large RGB values (0–255), we use smaller, normalized numbers that make training smoother and faster.

Data augmentation is another key step. It boosts the dataset by creating new variations of existing images. If we flip, rotate, or slightly change the brightness of a cat photo—it’s still a cat. These small tweaks help the model recognize objects under different conditions and reduce overfitting.

Famous datasets like MNIST (handwritten digits), CIFAR-10 (10 object categories), and ImageNet (millions of labeled images) are widely used to train and test convolutional neural networks. They serve as the gold standard for comparing CNN performance across research and applications.

2. Forward Propagation

During forward propagation, the image passes through the network one layer at a time. Each convolution layer applies filters to detect features, activation functions introduce non-linearity, and pooling layers condense the information. In the final stages, the fully connected layers generate predictions.

At first, since the network starts with random weights, these predictions are just guesses — it might even confidently mistake a dog for a banana. That’s the moment when real learning begins.

3. Backward Propagation

After the network makes a prediction, it checks how close that prediction is to the real answer using a loss function. In classification problems, the cross-entropy loss is the go-to choice. It punishes confident but wrong predictions more harshly, while being softer on uncertain ones.

Next comes backpropagation, which figures out how much each weight in the network contributed to the overall error. It uses calculus, mainly the chain rule, to calculate the gradients. These gradients show the direction of the change each weight needs. They also indicate the size of the change required to reduce the loss.

Think of it like tweaking a recipe. If your cake turns out too sweet, you cut down on sugar. Similarly, backpropagation guides the network by saying something like, “Hey, this filter in layer 3 reacts too strongly to dog images—tone it down a bit.”

4. Optimization Algorithms

Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) updates the model’s weights by moving them in the opposite direction of the gradient. It is just like walking downhill toward the lowest point. This point represents the minimum loss.

Adam (Adaptive Moment Estimation) takes SGD a step further by adjusting the learning rate for each weight on its own. It blends the idea of momentum — which smooths out updates — with adaptive learning rates, helping the model train faster and stay more stable. Because of this balance, Adam has become the most popular optimizer in deep learning today.

During training, the process repeats thousands of times: the model runs a forward pass, calculates the loss, backpropagates the error, and then updates its weights. With every cycle, the network’s random weights start to organize into meaningful feature detectors. The error keeps shrinking, accuracy improves, and step by step — the CNN learns how to see.

If you’d like to explore the math behind how neural networks learn, the book Deep Learning by Ian Goodfellow explains these ideas in depth — combining intuition with solid mathematical proofs.

Key Architectures that Changed AI: The Rise of Convolutional Neural Networks

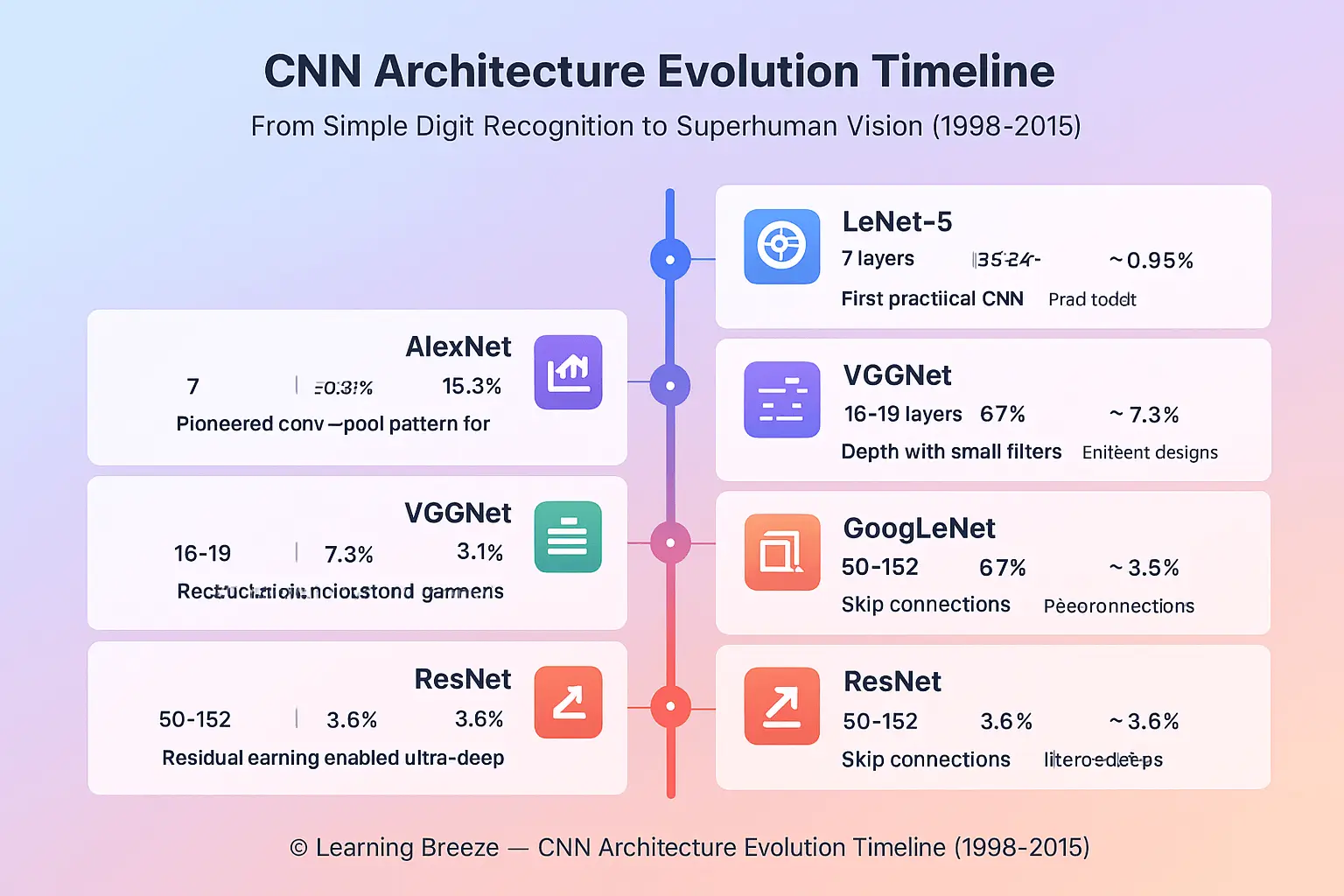

CNN evolution reads like a history of breakthroughs. Each landmark architecture pushed the boundaries of what machines could see and understand.

LeNet-5 (1998): The Pioneer

Yann LeCun’s LeNet-5 was the first practical CNN, designed to read handwritten zip codes for the U.S. Postal Service. With just seven layers, it proved that convolutional layers could automatically learn features better than hand-crafted algorithms.

LeNet-5 established the core pattern: convolution → pooling → convolution → pooling → fully connected. This blueprint still influences CNN architecture design today.

AlexNet (2012): The Revolution

AlexNet changed everything. In 2012, Alex Krizhevsky’s team entered the ImageNet competition with a deep CNN that crushed the competition, achieving 15.3% error compared to the second-place 26.2%.

What made AlexNet revolutionary? It went deeper (8 layers), used ReLU activation (faster training), employed dropout (preventing overfitting), and leveraged GPUs for parallel computation. This single architecture sparked the deep learning revolution and proved that bigger, deeper networks could achieve superhuman performance on complex visual tasks.

VGGNet (2014): The Power of Depth

VGGNet from Oxford’s Visual Geometry Group took a simple approach: go deeper with smaller filters. Instead of using large 7×7 or 11×11 kernels, VGG used stacks of 3×3 convolutions. The 16 and 19-layer versions (VGG-16, VGG-19) showed that depth matters tremendously for learning complex features.

VGG’s uniform architecture made it easy to understand and implement, making it popular for transfer learning applications.

GoogLeNet (2014): The Inception Module

Also called Inception v1, GoogLeNet introduced a radical idea: what if we apply multiple filter sizes in parallel? The Inception module uses 1×1, 3×3, and 5×5 convolutions simultaneously, then concatenates the results.

This architecture achieved better accuracy than VGG while using 12 times fewer parameters—a crucial advance for deploying CNNs on devices with limited computational resources.

ResNet (2015): Breaking the Depth Barrier

Microsoft Research’s ResNet solved a critical problem: very deep networks were actually performing worse than shallower ones due to vanishing gradients.

ResNet introduced skip connections (residual connections) that let information bypass layers. Instead of learning a function H(x), layers learn a residual F(x), and the output becomes F(x) + x. This simple trick enabled networks with 50, 101, even 152 layers to train effectively.

ResNet won ImageNet 2015 with a 3.6% error rate—better than human-level performance (around 5%). It remains one of the most influential architectures, with variants used across computer vision applications.

For those interested in implementing these architectures hands-on, Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and TensorFlow by Aurélien Géron provides practical code examples and detailed explanations.

Real-World Applications of Convolutional Neural Networks in Everyday Technology

CNNs have moved from research labs into everyday life, transforming industries and saving lives. Here’s where these deep learning models make the biggest impact.

Medical Imaging and Diagnostics

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can read X-rays, MRIs, and CT scans with incredible accuracy. They can spot breast cancer in mammograms, find tiny lung nodules, and detect diabetic retinopathy in eye scans—often matching or even surpassing human radiologists.

Their true value lies not in replacing doctors but in supporting them. A CNN can highlight a shadow a doctor might miss or confirm that a suspicious spot is actually harmless. This teamwork helps doctors diagnose faster and catch diseases earlier—when treatment works best.

At Stanford, a model called CheXNet reached radiologist-level accuracy in detecting pneumonia from chest X-rays. Meanwhile, Google’s DeepMind built AI systems that can identify more than 50 eye diseases from retinal scans. These technologies aren’t just experiments—they’re already being used in hospitals around the world.

Space Exploration and Astronomy

NASA uses CNNs to analyze satellite imagery and classify terrain on other planets. When rovers on Mars capture thousands of photos, CNNs quickly identify interesting geological features worth closer study.

Astronomers employ these networks to classify galaxies, detect exoplanets, and identify gravitational lensing events in telescope data. With surveys generating terabytes of images nightly, human analysis alone is impossible. CNNs make large-scale cosmic surveys practical.

Autonomous Driving

Self-driving cars rely heavily on CNN architecture for perception. Cameras capture the road scene, and CNNs process these frames 30+ times per second, detecting vehicles, pedestrians, lane markings, traffic signs, and obstacles.

Tesla’s Autopilot, Waymo’s self-driving system, and other autonomous platforms use multi-task CNNs. These networks simultaneously perform object detection. They also handle semantic segmentation, which involves labeling every pixel, and depth estimation. The network doesn’t just see a pedestrian—it knows where they are, which direction they’re moving, and predicts their next step.

Environmental Science and Conservation

CNNs help scientists to observe endangered species through camera trap images. Instead of manually reviewing millions of photos, neural networks automatically identify animals, count populations, and track migration patterns.

Marine biologists use underwater CNNs to identify fish species and monitor coral reef health. Climate researchers analyze satellite imagery to track deforestation, glacier retreat, and urban sprawl. These applications provide data crucial for conservation decisions.

Robotics and Manufacturing

Industrial robots rely on computer vision powered by CNNs to maintain quality control. They scan products on assembly lines, spotting tiny defects that humans might miss — and they do it at full production speed.

In warehouses, robots use CNN-based vision systems to move and navigate safely. On farms, agricultural robots use the same technology to recognize ripe fruits ready for picking. In every case, their ability to see and interpret visuals in real time makes automation efficient and practical.

The key idea behind all these examples is simple: CNNs turn raw pixels into real understanding. They help machines make smart, visual-based decisions — just like humans, but faster and with consistent accuracy.

Limitations and Challenges of Convolutional Neural Networks

Despite their power, CNNs aren’t perfect. Understanding their limitations is crucial for responsible deployment and future improvement.

Data Dependency and Overfitting

CNNs crave massive amounts of data. Training one from scratch usually needs thousands—or even millions—of labeled images. In specialized fields like rare diseases or unfamiliar animals, collecting enough data can be extremely costly or sometimes impossible.

Overfitting happens when the network memorizes the training examples instead of truly understanding the patterns behind them. It may perform amazingly well on the training set but fail miserably when facing new data. It’s like a student who memorizes every line from a textbook but can’t solve a fresh problem during the exam.

Techniques like data augmentation, dropout, and transfer learning can ease the problem, but they don’t fully remove the core need—having plenty of quality training data.

Computational Cost and Energy Consumption

Training deep CNNs demands serious hardware. A single training run on a large dataset can take days or weeks on powerful GPUs, consuming kilowatts of electricity. This creates both practical and environmental concerns.

Inference (using a trained network) is faster but still computationally intensive, especially for real-time applications like video analysis. Edge devices like smartphones struggle to run large networks without significant optimization.

The Black Box Problem

Why did the CNN classify this image as a dog? Which features influenced the decision? These questions are surprisingly hard to answer. Deep neural networks are notoriously opaque—we can see inputs and outputs, but the internal decision-making process remains mysterious.

This lack of explainability creates problems in high-stakes domains. A doctor needs to understand why a CNN flagged a scan as suspicious. A judge can’t accept “the algorithm said so” as justification for a decision affecting someone’s life.

Researchers are developing techniques like gradient-based class activation mapping to visualize what CNNs “see,” but full interpretability remains an open challenge.

Dataset Bias and Fairness

Convolutional Neural Networks learn directly from the data they’re trained on — including any hidden biases in that data. For example, if most training images show doctors as men and nurses as women, the model starts to associate those roles with gender. Similarly, if facial recognition systems are trained mostly on light-skinned faces, they often struggle to recognize darker-skinned individuals accurately.

These biases aren’t just theory — they’ve already caused real-world harm. Facial recognition tools have shown higher error rates for women and people of color. Image search engines have sometimes displayed stereotypical or even offensive results.

To reduce such bias, researchers focus on using diverse and balanced training data. They test models across different demographic groups. Researchers recognize that technical fixes alone can’t solve social inequalities. The AI community is actively developing fairness-aware systems, but creating truly unbiased technology is still a major challenge.

For a thoughtful exploration of AI ethics and bias, Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O’Neil examines how algorithms can reinforce inequality, providing crucial context for responsible AI development.

The Future of Convolutional Neural Networks: Expanding Beyond Image Recognition

CNN technology continues evolving rapidly. The next decade promises architectures and applications we’re only beginning to imagine.

Hybrid Models: CNN + Transformer

The latest breakthrough combines CNNs with Transformer models (originally developed for natural language processing). Vision Transformers (ViTs) and hybrid CNN-Transformer architectures leverage both local feature extraction (CNNs’ strength) and long-range dependencies (Transformers’ advantage).

These models achieve advanced performance on image classification, object detection, and image generation tasks. They represent the convergence of computer vision and natural language processing techniques.

Cross-Domain Learning and Multimodal AI

Future CNNs won’t just process images—they’ll integrate vision with text, audio, and sensor data. Imagine systems that understand a scene by combining what they see, hear, and read at the same time.

This enables richer AI assistants, robots that better understand context, and medical systems that analyze images alongside patient records and genomic data. The trend is toward holistic, multimodal understanding rather than isolated vision systems.

Edge AI and Sustainable Vision

As concern grows about AI’s energy footprint, researchers are developing efficient CNN architectures for edge devices. MobileNets, EfficientNets, and neural architecture search techniques automatically design networks optimized for mobile processors.

This enables powerful computer vision on smartphones, drones, IoT devices, and embedded systems without constant cloud connectivity. Privacy improves (data stays local) and energy consumption drops dramatically.

Toward Artificial General Intelligence

Current CNNs are great at handling specific visual tasks, but they still can’t generalize like humans do. For example, a network trained to recognize cats won’t recognize dogs unless it’s trained again.

The next generation of CNNs is changing that. These new models aim for few-shot learning. They learn from just a few examples. They also aim for zero-shot learning, which lets them recognize things they’ve never seen before. These advances bring us closer to creating AI systems that can truly adapt and learn flexibly.

At the hardware level, neuromorphic chips are stepping in to make CNNs faster and more efficient. These chips are designed to work like the human brain, allowing massive parallel processing while using less power. Companies like Intel (Loihi) and IBM (TrueNorth) are already building such processors, which could completely change how computer vision systems run.

The direction is clear: CNNs are moving beyond simple image recognition. They’re becoming key building blocks for general-purpose AI—systems that can see, interpret, and understand the world across many different forms of data.

Conclusion

Convolutional Neural Networks are one of humanity’s most powerful steps toward mimicking biological intelligence. Scientists were inspired by how the human visual cortex works. They turned its structure into mathematical models. These models create systems that can see and interpret images faster and more accurately than people.

We’ve explored how CNNs learn—layer by layer—starting from simple shapes and edges to recognizing complex patterns and objects. We’ve broken down their architecture. Convolution layers capture key features. Pooling layers condense information. Activation functions bring flexibility. Fully connected layers make final decisions. From early models like LeNet to groundbreaking ones like ResNet, each innovation has expanded what’s possible in computer vision.

CNNs have moved far beyond the research lab. They now diagnose medical conditions, navigate self-driving cars, explore outer space, protect endangered animals, and power the vision tools we use every day without even noticing.

But with great power comes real responsibility. CNNs still depend heavily on data, require massive computing power, and often act like “black boxes,” making their decisions hard to interpret. They can also carry human biases, reflecting the flaws in the data we feed them. As these systems grow smarter and more widespread, how we use them becomes just as important as how well they work.

The next era of CNNs will reach far beyond simple image recognition. The future includes hybrid architectures, multimodal learning, and brain-inspired hardware. These advancements point toward smarter and faster vision systems. They will be more adaptable and unlock possibilities we can barely imagine today.

Recommended Resources for Curious Minds

Ready to deepen your understanding of CNNs and deep learning? These carefully selected resources provide hands-on experience and comprehensive knowledge to support your learning journey:

- Programming Computer Vision with Python by Jan Erik Solem

- Neural Networks and Deep Learning: A Textbook by Charu C. Aggarwal

- The Hundred-Page Machine Learning Book by Andriy Burkov