From the red-clay hills of Georgia to the rolling bluegrass of Kentucky, a new American “Battery Belt” is rising faster than anyone predicted. Billions of dollars are pouring into gigantic factories—SK On in Commerce, Georgia; BlueOval SK in Glendale, Kentucky; Toyota’s massive plant in North Carolina—creating what may become the largest concentration of battery manufacturing on Earth. Yet even as these gigafactories come online in 2025, the core technology inside most of them is already approaching its physical ceiling. Solid-state battery technology is no longer a distant dream; it is the chemical breakthrough that will decide whether the United States becomes a true energy superpower or remains dependent on foreign supply chains.

The central conflict is simple: today’s lithium-ion batteries, brilliant as they are, rely on flammable liquid electrolytes. Range anxiety, long charging times, and the occasional terrifying fire remind us that we have pushed intercalation chemistry—the gentle shuttling of lithium ions into graphite layers—almost as far as physics allows. The next leap will not come from bigger motors or smarter software. It will come from industrial chemistry: replacing those volatile liquids with stable, high-performance solids.

This is the story of that switch—and why it matters to every driver, investor, and policymaker in America right now.

Introduction: The “White Gold” Rush

Drive along I-75 through Georgia and Kentucky today, and you’ll see construction cranes towering over fields that once grew tobacco. More than $60 billion in new battery-related investment has flooded the American South since 2022, fueled by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and a strategic realization: whoever controls advanced batteries controls the 21st-century economy.

But the clock is ticking. Even with 400+ mile EVs now common, consumers still worry about charging speed, winter range loss, and—most viscerally—fires. Thermal runaway events, though statistically rare, dominate headlines when they happen. The National Transportation Safety Board continues to document cases where liquid electrolytes turn a minor crash into an inferno.

The core thesis is straightforward: mechanical engineering has taken us far, but the final barrier is chemical. To break through 500-mile range, 10-minute charging, and near-zero fire risk, we must abandon flammable organic solvents and embrace solid electrolytes. The revolution will be won or lost in laboratories working with ionic conductivity, dendrite formation, and the mysterious Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI). And the winners will redefine transportation, grid storage, and American industrial might for decades.

Solid-State Battery Technology: The Chemistry Behind the Switch from Liquid to Solid Electrolytes

1. The Flammable Weakness

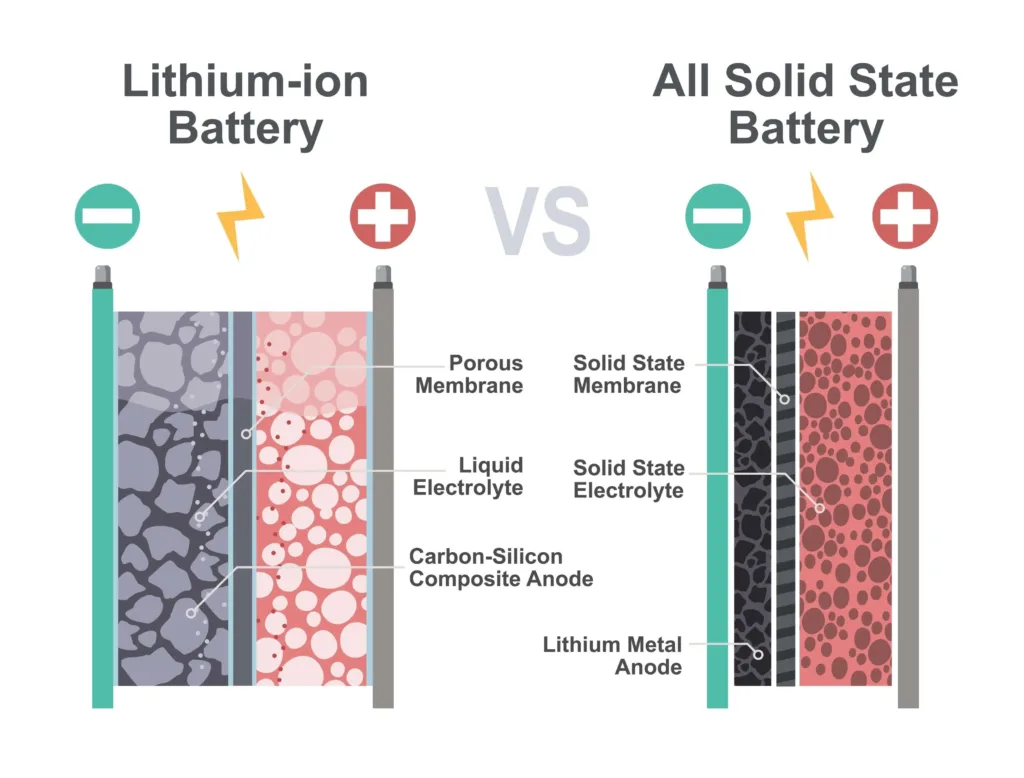

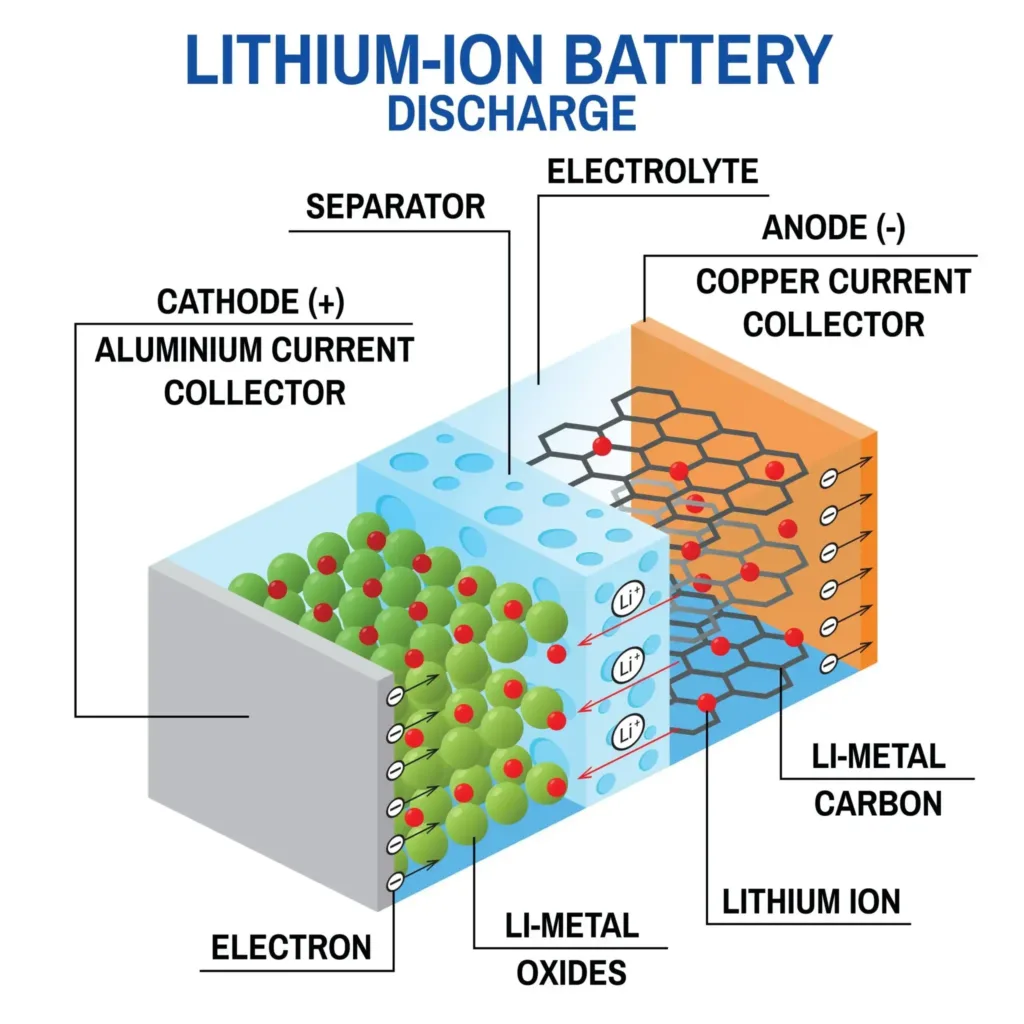

To understand why solid-state battery technology signifies such a breakthrough, we first need to examine what makes current EV batteries vulnerable. Every lithium-ion battery in today’s electric vehicles relies on liquid organic solvents—typically carbonate-based compounds—to shuttle lithium ions between the anode and cathode during charging and discharging cycles.

This liquid electrolyte enables ionic conductivity, allowing charged particles to move freely through the battery. During the intercalation process, lithium ions insert themselves into the layered structure of the cathode material, storing energy. When we press the accelerator, these ions flow back through the liquid, generating the current that powers our motor.

Where is the problem? These organic solvents are inherently flammable. If the thin polymer separator between the positive and negative electrodes fails—whether from manufacturing defects, physical damage, or dendrite puncture—the liquid electrolyte becomes fuel for a chemical fire. This cascading failure, known as thermal runaway, can reach temperatures exceeding 1,000 °F in seconds. The solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) layer, which normally protects the anode, breaks down under these extreme conditions, accelerating the disaster.

2. The Solid Solution

Solid-state batteries remove this fundamental vulnerability by replacing the flammable liquid with a solid electrolyte—a material that conducts ions while remaining chemically and thermally stable. Think of it as replacing gasoline with concrete as your medium for energy transfer: far less efficient initially, but infinitely safer once optimized.

Here’s the head-to-head comparison readers scan for:

| Feature | Lithium-Ion (Liquid Electrolyte) | Solid-State Battery |

|---|---|---|

| Electrolyte type | Liquid organic carbonates | Solid (oxide, sulfide, or polymer) |

| Energy density | 250–300 Wh/kg | 350–500+ Wh/kg (theoretical) |

| Safety (thermal runaway risk) | High – flammable liquid | Very low – no flammable liquid |

| Ionic conductivity at RT | ~10⁻² S/cm | 10⁻⁴ to 10⁻² S/cm (sulfides approach liquid) |

| Cycle life | 500–2,000 cycles | Potentially 5,000+ cycles |

| Fast-charge capability | Limited by heat & dendrites | Significantly improved |

| Operating temperature range | Narrow (degrades outside 0–45 °C) | Wider, especially cold-tolerant |

| Manufacturing maturity | Decades of mass production | Pilot → early commercial (2025–2028) |

| Dendrite Resistance | Poor (separator can be pierced) | Better (but cracks remain a challenge) |

3. Deep Dive: The Three Main Contenders

The race toward commercialized solid-state battery technology isn’t a single horse race—it’s three different chemical approaches competing at the same time. Each has champions in the research community and backing from major automotive manufacturers.

A. Oxides (Ceramics): The Stable Giant

Oxide-based solid electrolytes, particularly lithium lanthanum zirconium oxide (LLZO) garnets, offer exceptional chemical stability and high ionic conductivity at room temperature. These ceramic materials don’t react with lithium metal anodes, making them ideal for next-generation battery designs.

The drawback? They’re brittle. Ceramic electrolytes can crack under the mechanical stress of battery cycling or vehicle vibrations. Manufacturing requires high-temperature processing (often above 1,000°C), making production expensive and energy-intensive. Companies like QuantumScape are betting big on solving the brittleness problem through innovative thin-film manufacturing techniques.

B. Sulfides: The Soft Contender

Sulfide-based electrolytes represent a compelling choice. Materials like Li₁₀GeP₂S₁₂ (LGPS) are softer and more moldable than ceramics, allowing for better contact with electrode materials. They can be processed at lower temperatures, potentially reducing manufacturing costs.

The catch? Sulfide electrolytes are moisture-sensitive. Expose them to air, and they release toxic hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) gas—the same compound that smells like rotten eggs and can be lethal at high concentrations. This necessitates hermetically sealed manufacturing environments and raises serious questions about end-of-life recycling safety. Toyota, holding the most patents in solid-state battery technology, has invested heavily in sulfide chemistry despite these challenges.

C. Polymers: The Flexible Future

Polymer electrolytes offer unprecedented flexibility and ease of manufacturing. These materials can be processed using conventional coating techniques comparable to current battery production, potentially accelerating commercialization timelines.

However, polymer solid electrolytes suffer from lower ionic conductivity at room temperature compared to ceramics or sulfides. Most require elevated operating temperatures (60-80°C) to achieve acceptable performance, which somewhat defeats the purpose of solid-state advantages. Researchers are exploring composite approaches—mixing polymer matrices with ceramic nanoparticles—to get the best of both worlds.

The “Dendrite” Problem: Chemistry’s Biggest Villain

If thermal runaway is the dramatic villain of battery safety, dendrites are the silent assassin, undermining performance and longevity. Understanding dendrite formation is crucial to appreciating why the solid-state vs lithium-ion debate matters so much.

Dendrites are microscopic, needle-like lithium crystals that grow during the charging process. When lithium ions are deposited unevenly on the anode surface—often due to localized current density variations—they form these spiky protrusions instead of a smooth coating. The name comes from the Greek word for “tree,” and under an electron microscope, they genuinely resemble a crystalline forest growing from the electrode surface.

In liquid lithium-ion batteries, dendrites spell disaster. As they grow longer with each charge cycle, they eventually puncture the polymer separator, creating a short circuit between the anode and cathode. This triggers thermal runaway, potentially causing fires or explosions. Even before catastrophic failure, dendrite formation consumes active lithium, degrading battery capacity over time.

Solid-state batteries were initially hoped to solve this problem entirely. After all, a rigid ceramic electrolyte should physically block dendrite growth, right? Reality proved more complicated. While solid electrolytes resist puncture better than polymer separators, they face a different challenge: dendrites can propagate through grain boundaries or even crack brittle ceramic materials under the mechanical stress of their growth.

The Industrial Angle: “Black Mass” & The Circular Economy

Here’s an inconvenient truth about America’s battery ambitions: we can’t mine lithium, cobalt, and nickel fast enough to meet projected EV demand. Even with new domestic mining projects approved under the Inflation Reduction Act, geological constraints and environmental regulations mean supply will lag behind demand for at least a decade.

We must recycle. And that brings us to one of industrial chemistry’s most fascinating challenges: recovering valuable metals from “black mass.”

1. What is Black Mass?

When lithium-ion batteries reach end-of-life, they’re mechanically shredded in specialized facilities. The resulting powder—a chaotic mixture of lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese, copper, aluminum, and carbon—is called black mass. It looks like dark, fine sand, but it’s actually a treasure trove of materials that took immense energy and environmental cost to originally extract and refine.

A single EV battery pack holds roughly 8-10 kg of lithium, 14-16 kg of nickel, and 4-5 kg of cobalt. At current market prices, that means $1,500-2,000 in raw materials alone. Multiply that across millions of vehicles reaching end-of-life by 2030, and battery recycling becomes a multi-billion dollar industry with profound implications for supply chain security.

2. The Process: Hydrometallurgy (The Chemistry of Recovery)

Recovering pure metals from black mass requires sophisticated chemical processing, primarily through hydrometallurgy—using aqueous solutions to selectively dissolve and separate metals.

The process begins with leaching. Black mass is mixed with acids (typically sulfuric acid or hydrochloric acid) that dissolve the metal oxides into ionic form. For example, lithium cobalt oxide—the cathode material in many current batteries—reacts with sulfuric acid:

LiCoO₂ + H₂SO₄ → Li⁺ + Co²⁺ + SO₄²⁻ + H₂O

This simplified equation shows a complex multi-step process, but the principle is straightforward: acids break down the solid compounds, releasing metal ions into solution.

The real chemistry magic happens in precipitation and separation. Because different metals precipitate (solidify) out of solution at different pH levels, recyclers can selectively recover materials one by one. Adjust the pH to 3.5, and copper precipitates. Raise it to 5.8, and nickel drops out. At pH 8.5, cobalt crystallizes. Lithium typically remains in solution longest and can be recovered through evaporation or extra chemical treatment.

This sequential extraction enables recyclers to produce battery-grade materials—often purer than virgin mined materials—because each precipitation step is essentially a purification process.

3. Why This Matters: Building the Closed Loop

Companies like Redwood Materials (founded by Tesla’s former CTO) and Ascend Elements are constructing massive recycling facilities across the Battery Belt, creating a circular economy for battery materials. Redwood’s Nevada facility aims to recycle 100 GWh of batteries annually by 2025—enough material to produce batteries for 1 million EVs.

This closed-loop approach addresses multiple challenges at the same time. It reduces mining dependence, lowers environmental impact (recycling uses 70% less energy than virgin material production), improves supply chain resilience, and creates domestic manufacturing jobs.

For solid-state batteries, recycling presents new opportunities and challenges. While the basic hydrometallurgical principles remain similar, sulfide-based electrolytes require additional safety protocols due to H₂S release. Conversely, ceramic electrolytes might be cleaned and reused directly rather than chemically broken down—a potentially more efficient approach that researchers are actively exploring.

Market Outlook: Who Leads the USA in Solid-State Battery Technology?

The transition from laboratory prototypes to mass-market solid-state EVs follows a predictable but challenging trajectory. Understanding this timeline helps separate genuine progress from marketing hype.

2025: Pilot Lines and Hybrid Batteries

We’re entering the year of demonstration. Companies like QuantumScape and Solid Power are transitioning from coin-cell prototypes to automotive-scale pouch cells. These aren’t yet true solid-state batteries in the purest sense—many use “semi-solid” or hybrid designs with gel-like electrolytes that combine liquid and solid properties.

Toyota has announced plans for limited production vehicles featuring solid-state technology by late 2025, though initially these will be expensive, low-volume models aimed at proving the technology rather than transforming the market. Think of them as the battery equivalent of early EVs like the Tesla Roadster—proof-of-concept rather than mass-market disruptors.

2027-2028: First Mass-Market Adoption

If manufacturing scale-up proceeds without major setbacks, we should see the first reasonably priced consumer EVs with solid-state batteries hitting dealerships around 2027-2028. These vehicles will likely offer 400-500 mile ranges, 10-15 minute fast charging times, and significantly improved safety profiles compared to current lithium-ion EVs.

BMW has partnership agreements targeting 2028 launches. Ford and GM, while more cautious publicly, are investing heavily in the technology through venture capital arms and research collaborations.

Key Players in the American Ecosystem

QuantumScape (QS) remains the highest-profile pure-play solid-state battery company, backed by Volkswagen and Bill Gates. Their ceramic separator technology has demonstrated impressive performance in testing, but manufacturing at scale remains unproven. The stock trades with extreme volatility, reflecting the high-risk, high-reward nature of the sector.

Solid Power (SLDP) takes a different approach with sulfide-based electrolytes, emphasizing manufacturability and partnerships with BMW and Ford. Their strategy focuses on retrofitting existing battery production lines rather than building entirely new facilities—potentially faster but perhaps more limited in ultimate performance.

Toyota holds more solid-state battery patents than any other entity globally—over 1,000 according to recent analysis. The Japanese automaker’s commitment to the technology is unambiguous, though their timeline has repeatedly shifted. Their advantage lies in decades of materials science skill and willingness to invest for long-term returns rather than quarterly results.

Note for Investors: Manufacturing is the Moat

Here’s the uncomfortable reality for investors excited about solid-state battery technology: demonstrating superior performance in a laboratory is the easy part. Scaling production to millions of cells annually while maintaining quality, driving down costs, and achieving acceptable manufacturing yields—that’s where companies will succeed or fail.

Current lithium-ion batteries benefit from decades of manufacturing optimization. Production costs have fallen 97% since 1991 through continuous incremental improvements. Solid-state batteries are starting from scratch, facing challenges in material handling, interface engineering, and quality control that aren’t yet fully understood.

The winning companies won’t necessarily be those with the best laboratory performance. They’ll be the ones that solve manufacturing challenges—achieving 95%+ production yields, eliminating defects, and driving costs below $100/kWh. That milestone might arrive by 2028 for early leaders, or it might take until 2032. Anyone claiming certainty about the timeline is either naive or selling something.

FAQs: Your Solid-State Battery Questions Answered

Yes, solid-state batteries do exist, but mostly in prototype or small-scale production. Companies like Toyota, QuantumScape, and Samsung have working cells, but they’re not ready for mass-market EVs due to cost, durability issues, and manufacturing limitations.

Solid-state batteries are expected to last 2–3 times longer than today’s lithium-ion packs—potentially 15 to 20 years or over 500–2,000 charge cycles. Real-world lifespan will depend on mass-production breakthroughs that stabilize electrolyte interfaces.

Their biggest challenge is interface instability—the solid electrolyte and lithium metal can form cracks, causing short circuits. Large-scale manufacturing is also extremely difficult, making them expensive and limiting commercial rollout.

EVs don’t use solid-state batteries yet because current prototypes struggle with scalability, charging durability, and high production costs. Automakers need millions of stable cells per year, and solid-state technology isn’t mature enough for that level of manufacturing.

Most experts expect limited commercial use by 2027–2028 in premium devices or niche EV models. Full mass-market adoption will likely take until early 2030s, once cost, safety, and production challenges are solved.

Absolutely. Solid-state batteries promise faster charging, longer range, cooler operation, and higher safety. Once manufacturing problems are solved, they’re expected to become the next major leap in EV and consumer battery technology.

Conclusion

The future of electric vehicles won’t be determined by aerodynamics, motor efficiency, or even charging infrastructure. It will be determined by chemistry—specifically, by our ability to replace flammable liquids with stable solids while maintaining the ionic conductivity that makes batteries work.

Solid-state battery technology signifies one of those rare inflection points where materials science, industrial chemistry, and manufacturing engineering converge to enable a genuine paradigm shift. The challenges are formidable: scaling production, controlling dendrite formation, managing interfacial resistance, and building a circular economy for increasingly complex materials.

Yet the potential rewards—safer vehicles, doubled driving ranges, dramatically faster charging, and reduced dependence on imported materials—make this one of the most consequential technological races of the 2020s. The Battery Belt rising across America’s South isn’t just an industrial development story. It’s a chemistry revolution that will determine whether electric vehicles become truly ubiquitous or remain a premium product for early adopters.

As we’ve explored, understanding this transformation requires thinking beyond automotive engineering to appreciate the atomic-level processes that govern how lithium ions move through materials, how dendrites nucleate and grow, and how we can recover and reuse these precious materials through hydrometallurgy and the circular economy.

The companies that master these challenges—not just in the laboratory but in gigafactories producing millions of cells annually—will define transportation for the next half-century. And for investors, engineers, students, and anyone fascinated by how chemistry shapes our technological future, there’s never been a more exciting time to pay attention.

The white gold rush is just beginning. The question isn’t whether solid-state batteries will replace lithium-ion technology, but when—and who will lead the transformation.

Continue Your Learning Journey

For a hands-on understanding of the concepts discussed, we recommend these resources available on Amazon:

- Towards Next Generation Energy Storage Technologies by Minghua Chen

- Handbook Of Solid State Batteries by Nancy J Dudney

- The Powerhouse: Inside the Invention of a Battery to Save the World by Steve Levine

- Electrochemical Energy Storage Lab Kit