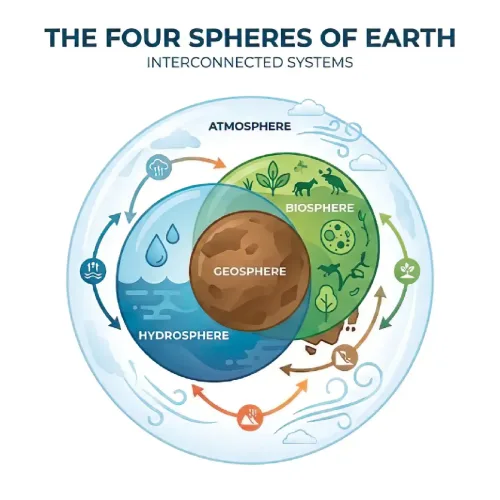

Earth’s oceans are not just beautiful to look at, they are the beating heart of our planet’s entire life-support system. If you have ever wondered why Earth’s oceans matter so profoundly, the answer lies in the way that they shape everything around us like climate and oxygen. They influence biodiversity and food sources. They even impact the weather patterns that decide the fate of civilizations. Oceans cover approximately 71% of Earth’s surface and contain 97% of all water on the planet. They drive weather patterns, generate oxygen, absorb carbon dioxide, regulate global temperatures, and host the most biodiverse ecosystems we have ever discovered. Without oceans, Earth would be as lifeless as Mars.

From the swirling thermohaline circulation that balances temperature to the phytoplankton that produce half of our oxygen, the ocean is the engine behind our survival. This article dives deep — guided by science, grounded in data — to explore how the oceans work, why they are under threat, and what humanity must do to protect them. Each section builds a full picture of Earth’s most powerful system and why it demands attention more than ever.

Earth’s Oceans Matter: Key Statistics That Reveal Why Our Blue Planet Depends on Them

Numbers don’t lie, and when it comes to oceans, the data is staggering. The world’s oceans hold about 1.335 billion cubic kilometers of water. The average depth is roughly 3,688 meters (12,100 feet), with the deepest point, the Mariana Trench, plunging to nearly 11,000 meters below the surface.

But volume and depth are just the beginning. Oceans produce at least 50% of the our planet’s oxygen, primarily through phytoplankton, they are microscopic organisms that photosynthesize just like trees. Every second breath we take comes from the ocean, not the rainforest.

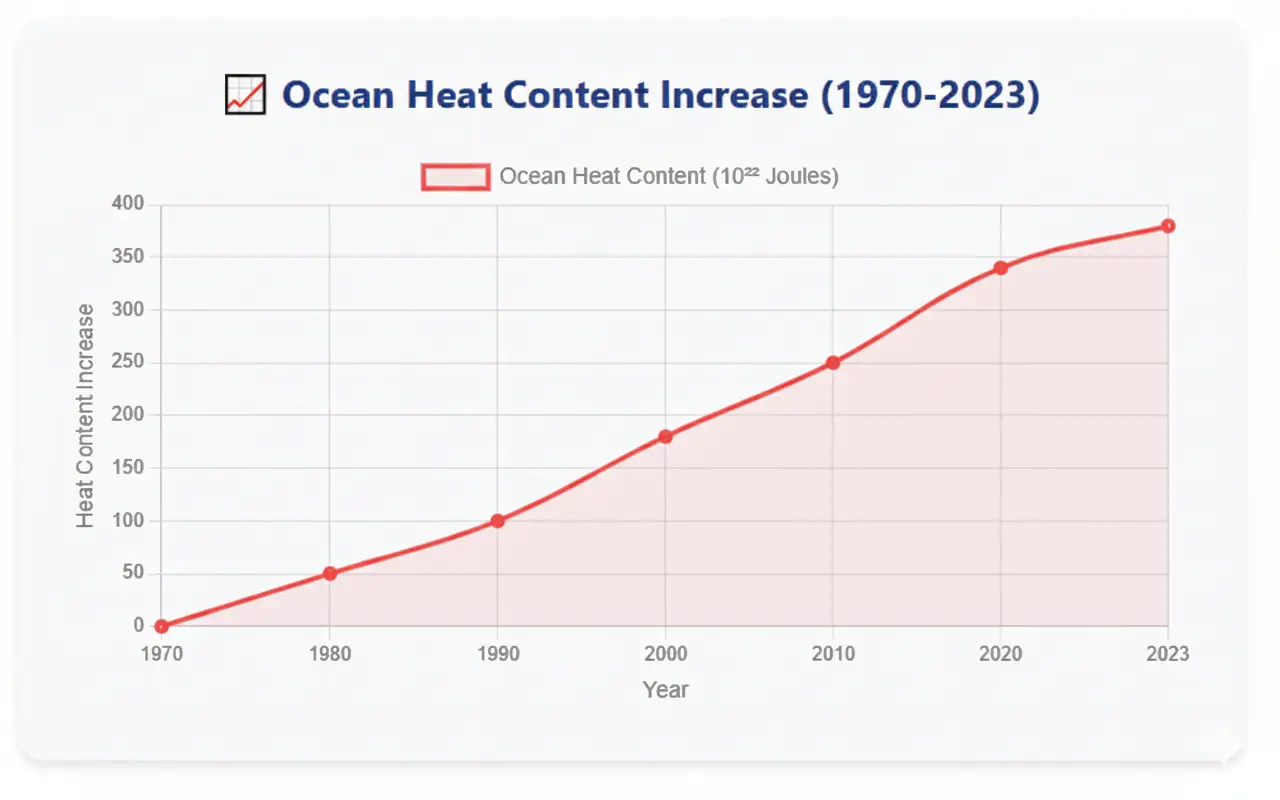

Ocean heat content has been rising dramatically. Since the 1970s, the oceans have absorbed more than 90% of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases. This is not just warming the surface waters, it is fundamentally altering the circulation patterns, weather systems, and marine ecosystems. Recent studies have shown that ocean heat content has reached at the record levels year after year, with 2023 marking the hottest ocean temperatures ever recorded.

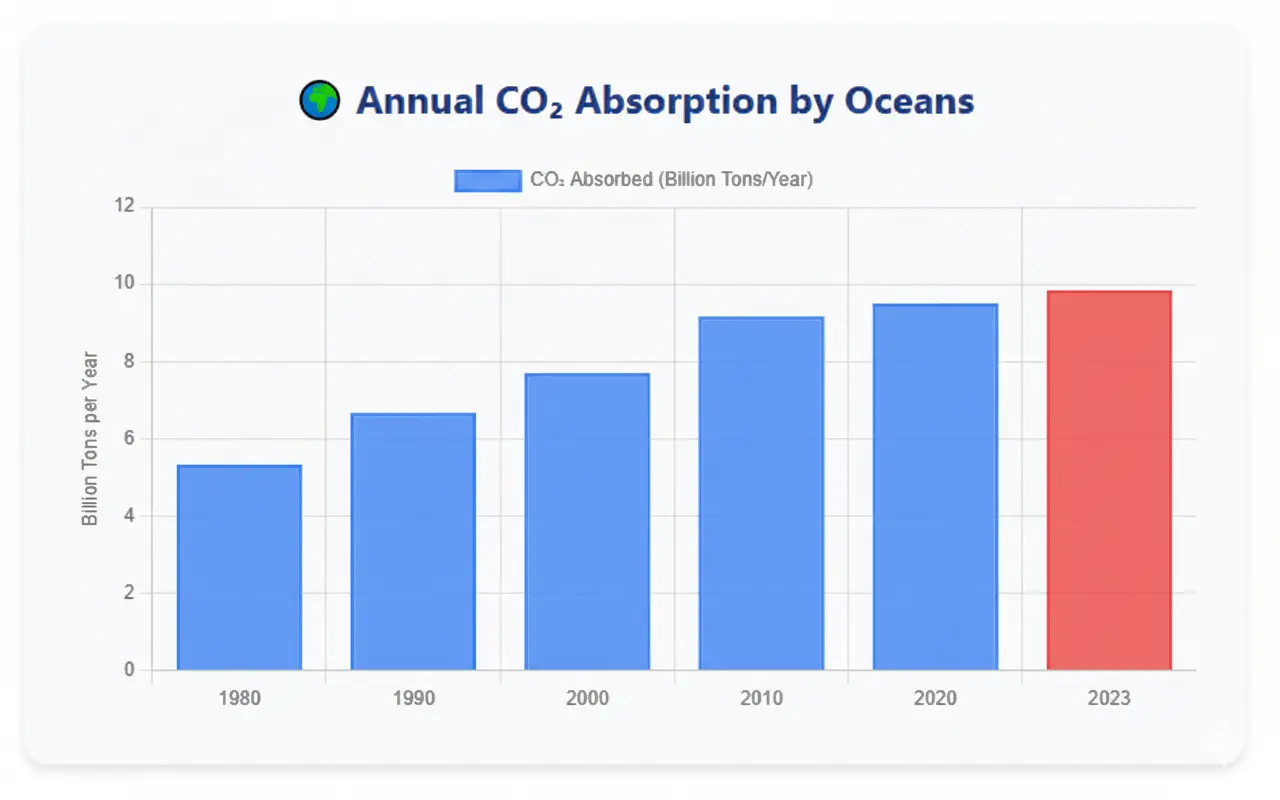

Oceans also absorb about 25-30% of human-generated carbon dioxide emissions annually. That’s roughly 10 billion tons of CO₂ per year pulled out of the atmosphere. Without this natural carbon sink, atmospheric CO₂ levels would be far higher, and global warming would be accelerating even faster.

These numbers matter because they reveal a simple truth: the ocean is not just the part of Earth’s climate system. It is the climate system. Every storm, every drought, every heatwave—oceans are pulling the strings behind the scenes.

Since 1970, oceans have quietly soaked up nearly 400 × 10²² joules of extra heat — that’s like detonating 5 Hiroshima bombs every second for 50 years.

Oceans are now absorbing almost 10 billion tons of CO₂ every year — double what they took in during the 1980s. Our seas are working overtime.

Oceans: Earth’s true superheroes 🌊💨🔥Cover 71% of the planet Produce over 50% of our oxygen Absorb 90% of excess heat Remove 25–30% of CO₂ every year

How Oceans Make Earth Habitable — The Science Explained

The ocean acts like Earth’s master engineer. It constantly balances heat, moves energy across the planet, and keeps our atmosphere chemically stable. Let’s explore more!

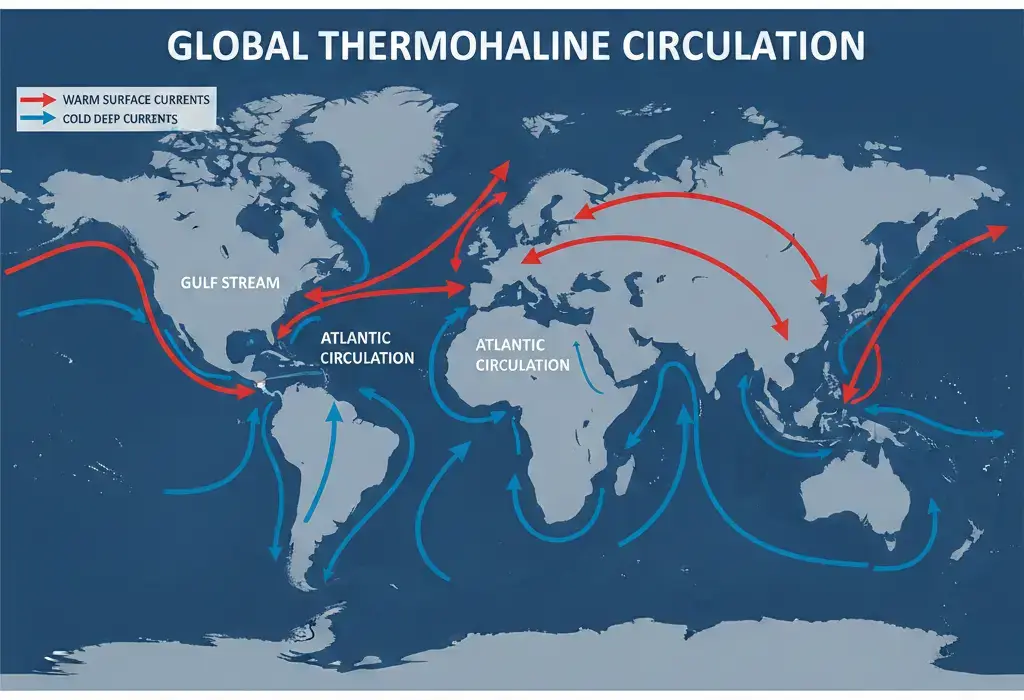

A. Thermohaline Circulation

Imagine a conveyor belt moving heat, salt, and nutrients across the entire globe. That’s known as thermohaline circulation—often called the “global conveyor belt”—and it’s one of the most important climate regulators on Earth.

Here’s how it works: warm, salty water from the tropics travels toward the poles. As it moves north, it cools down and becomes denser. Near Greenland and the Arctic, this cold, dense water sinks deep into the ocean and begins a slow journey along the ocean floor back toward the equator. Meanwhile, surface currents bring warm water northward to replace it.

This process distributes heat from the equator to the poles, preventing the extreme temperature differences between regions. It’s why Europe enjoys relatively mild winters despite being at the same latitude as frigid parts of Canada. The Gulf Stream is a major component of this circulation that carries warm water from the Caribbean across the Atlantic, warming the European coastline.

But there’s a problem: climate change is disrupting this delicate balance. Melting polar ice adds freshwater to the North Atlantic, reducing salinity and making water less dense. If water does not sink as it should, the entire circulation system could weaken or even shut down, this scenario scientists call an AMOC (Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation) slowdown. The consequences would be catastrophic: Europe plunging into ice-age-like winters, tropical regions overheating, and weather patterns collapsing worldwide.

B. The Carbon Pump Systems

Oceans don’t just absorb carbon dioxide at the surface, they actively pump it into the deep sea through two main mechanisms: the biological pump and the solubility pump. Together, these form the global carbon pump, one of Earth’s most critical climate stabilizers.

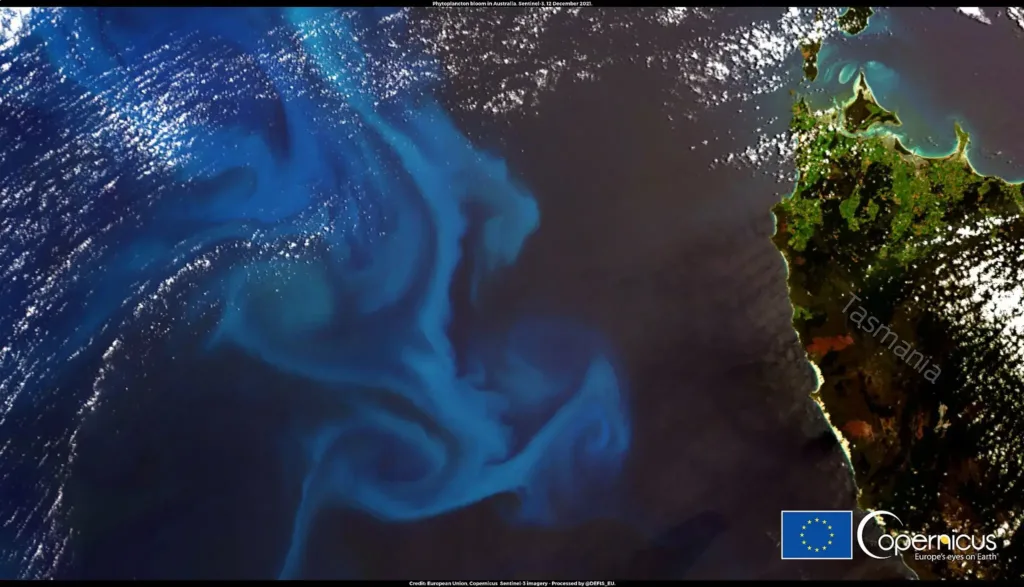

The biological pump starts with phytoplankton. These microscopic plants capture CO₂ during photosynthesis, converting it into organic matter. When phytoplankton die, their bodies—along with fecal pellets from the zooplankton that eat them—sink toward the ocean floor in a process called “marine snow.” This carbon can remain locked in deep-sea sediments for thousands of years.

The solubility pump is even simpler: cold water absorbs more CO₂ than warm water. At high latitudes, frigid surface waters soak up atmospheric carbon dioxide before sinking into the deep ocean as part of thermohaline circulation. This carbon remains trapped until the water eventually resurfaces centuries or millennia later.

Why does this matter? Because weakening pump systems threaten the climate stability. Warmer oceans absorb less CO₂. Disrupted circulation patterns reduce the efficiency of carbon sequestration. Declining phytoplankton populations—caused by warming, acidification, and nutrient changes—mean less biological carbon pumping. If these systems falter, more CO₂ stays in the atmosphere, accelerating global warming even faster.

C. Ocean–Atmosphere Coupling

The ocean and atmosphere are not separate systems—they are intimate partners constantly exchanging heat, moisture, and energy. This coupling drives virtually every weather pattern on Earth, from daily rainfall to seasonal monsoons to devastating hurricanes.

Sea surface temperature (SST) is the control dial for atmospheric behavior. Warm ocean surfaces evaporate more water, pumping moisture into the air that eventually falls as rain. Cold surfaces suppress evaporation, creating drier conditions. Even a temperature change of just 1-2 °C can shift entire monsoon systems, alter storm tracks, and trigger extreme weather events.

Consider El Niño and La Niña—cyclical warming and cooling patterns in the Pacific Ocean that influence global weather for months at a time. During El Niño, warm water spreads across the eastern Pacific, causing droughts in Australia and flooding in South America. La Niña flips the script, bringing wet conditions to Australia and dry spells to California. These are not isolated ocean events; they’re the ocean literally reprogramming Earth’s atmospheric circulation.

Rising ocean temperatures mean more energy in the system. That translates to more intense hurricanes, stronger atmospheric rivers, and more frequent marine heatwaves that devastate ecosystems and coastal economies. Understanding ocean climate regulation isn’t optional anymore—it’s essential for predicting and preparing for the climate future we are building.

The Ocean as the Cradle of Life — Biodiversity & Ecosystems

The ocean is Earth’s largest living space, supporting a dazzling and complex web of life—from the microbial to the monumental.

A. Marine Biodiversity Overview

If Earth is a library of life, the ocean holds most of the books. Marine biodiversity encompasses everything from microscopic bacteria to blue whales weighing 200 tons—the largest animals ever to exist on Earth.

Scientists estimate that oceans contain anywhere from 700,000 to over 1 million species, but we have only identified about 250,000 so far. The deep sea alone—Earth’s largest habitat—remains 95% unexplored, meaning millions of species might be living in darkness we have never penetrated.

Coral reefs, despite covering less than 0.1% of the ocean floor, support roughly 25% of all marine species. They are biodiversity hotspots rivaling tropical rainforests. Coastal systems like estuaries serve as nurseries for fish, filtering pollution and protecting shorelines from storms. Open ocean pelagic zones host migratory species like tuna, sharks, and sea turtles that travel thousands of miles annually.

This biodiversity isn’t just beautiful—it’s functional. Every species plays a role in nutrient cycling, energy transfer, and ecosystem stability. Lose one piece, and the entire web starts unraveling.

B. Phytoplankton: Earth’s Invisible Forest

You can’t see them without a microscope, but phytoplankton are doing more heavy lifting than all the rainforests combined. These single-celled organisms—diatoms, dinoflagellates, cyanobacteria—drift through sunlit surface waters, performing photosynthesis at scales that boggle the mind.

Phytoplankton oxygen production accounts for at least 50-80% of Earth’s oxygen supply (estimates vary by study). They fix carbon dioxide into organic compounds, forming the base of virtually every marine food web. When they die and sink, they transport carbon to the deep ocean—the biological pump we discussed earlier.

But phytoplankton populations are declining in many regions due to warming waters, ocean acidification, and changing nutrient availability. Some studies suggest global phytoplankton biomass has decreased by about 40% since 1950. If this trend continues, we’re not just losing marine food sources—we’re losing a primary oxygen generator and carbon sink.

C. Keystone Ecosystems

Some ecosystems punch far above their weight. Mangrove forests, seagrass meadows, and salt marshes—collectively known as blue carbon ecosystems—sequester carbon at rates up to 40 times faster than terrestrial forests.

Mangroves grow in tropical coastal zones, their tangled root systems trapping sediment and organic matter. They protect coastlines from storm surges, serve as nurseries for fish and crustaceans, and store massive amounts of carbon in waterlogged soils where decomposition is slow.

Seagrass meadows provide food for sea turtles, manatees, and dugongs while stabilizing seafloors and filtering water. Salt marshes buffer coastal areas from erosion and flooding while supporting birds, fish, and invertebrates.

Despite their importance, we’ve lost 30-50% of global mangroves in the past 50 years due to coastal development, aquaculture, and pollution. Restoring these ecosystems isn’t just good for biodiversity—it’s one of the most cost-effective climate solutions available.

D. Deep-Sea Mysteries

The deep ocean is Earth’s final frontier—more remote and less explored than the surface of Mars. Below 200 meters, sunlight fades completely. Below 1,000 meters, pressure becomes crushing. Yet life thrives in this alien environment.

Hydrothermal vents spew superheated water rich in minerals from cracks in the ocean floor. Around these vents, entire ecosystems flourish without sunlight, powered by chemosynthetic bacteria that convert hydrogen sulfide into energy. Giant tube worms, eyeless shrimp, and ghostly fish cluster around these oases in the abyss.

Extremophiles—organisms that thrive in extreme conditions—have revolutionized our understanding of life’s possibilities. Enzymes from deep-sea bacteria are now used in medical research, industrial processes, and biotechnology. The deep sea might hold cures for diseases we have not solved yet.

But we’re mining and polluting these ecosystems before we even understand them. Deep-sea trawling destroys ancient coral forests. Plastic debris has reached the Mariana Trench. We are jeopardizing knowledge and resources we have not even discovered yet.

Human Dependence on the Oceans — Food, Economy & Culture

The sea keeps our world running in so many ways. It supports global trade, fuels major industries, and feeds billions. In short, it quietly holds up more of our daily life than we notice.

A. Fisheries & Global Food Security

Over 3 billion people rely on seafood as their primary source of protein. For coastal communities in developing nations, fish isn’t a dietary choice—it’s survival. The ocean provides roughly 17% of all animal protein consumed globally, and in some island nations, that figure exceeds 50%.

Wild-capture fisheries use more than 40 million people directly, with another 200 million jobs depending on related industries like processing, distribution, and retail. Sustainable fisheries management is not just about conservation—it’s about maintaining livelihoods and preventing humanitarian crises.

But overfishing has pushed many stocks to collapse. The Mediterranean bluefin tuna, once abundant, nearly went extinct before strict regulations pulled it back from the brink. West African fisheries face pressure from both industrial trawlers and climate-driven species migrations. When fish populations crash, communities lose income, nutrition, and cultural identity all at once.

B. Blue Economy

The ocean economy is worth an estimated $2.5 trillion annually—larger than the GDP of most countries. Shipping routes carry 90% of global trade, moving everything from smartphones to grain across vast distances. Without maritime transport, globalization simply wouldn’t exist.

Coastal tourism generates hundreds of billions in revenue each year. Beaches, diving spots, whale watching, and recreational fishing support millions of jobs worldwide. Cities like Miami, Barcelona, and Sydney owe much of their prosperity to ocean access and marine attractions.

Offshore energy—both fossil fuels and renewables—is expanding rapidly. Wind farms are sprouting in coastal waters from Europe to Asia. Wave and tidal energy projects are moving from concept to reality. The ocean is becoming humanity’s next energy frontier, for better or worse.

C. Global South & Coastal Communities

Climate impacts are not distributed equally. Small island developing states (SIDS) like the Maldives, Tuvalu, and Kiribati face existential threats from sea-level rise despite contributing almost nothing to global emissions. Their entire nations could disappear within this century.

Low-lying deltas in Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Egypt—home to hundreds of millions—are experiencing saltwater intrusion, coastal erosion, and increasing storm damage. These communities lack the resources to build seawalls or move entire cities. Climate adaptation isn’t a choice; it’s an urgent necessity with limited options.

The pattern is clear: those most dependent on ocean resources are often least responsible for their degradation yet most vulnerable to the consequences. Climate justice and ocean health are inseparable.

D. Cultural Connection

Humans have been ocean people for millennia. Polynesian navigators crossed the Pacific using only stars, waves, and bird migrations—feats of knowledge and courage that shaped entire civilizations. Coastal cultures from Norway to Japan to Peru built identities around fishing, boat-building, and maritime traditions.

Indigenous ocean knowledge holds solutions modern science is only beginning to recognize. Traditional fishing practices, seasonal migration patterns, and reef management techniques evolved over generations of close observation. When we lose ocean ecosystems, we also lose these knowledge systems—a cultural extinction parallel to biological extinction.

The Triple Threat: Warming, Acidification & Deoxygenation

Human activities have unleashed a powerful environmental pressure called “The Triple Threat,” and it’s now pushing our marine ecosystems to their breaking point.

A. Ocean Warming

Ocean temperatures have risen approximately 0.13°C per decade since the 1980s. That might sound small, but remember—oceans are massive. The energy needed to heat that much water is staggering, equivalent to dropping multiple atomic bombs into the sea every second.

Marine heatwaves—periods of abnormally high ocean temperatures lasting weeks or months—have become five times more frequent since the early 20th century. The 2016 heatwave that struck the Great Barrier Reef bleached 93% of the reef system, killing vast stretches of coral that had survived for centuries.

Coral bleaching occurs when water temperatures exceed corals’ tolerance thresholds, causing them to expel the symbiotic algae that give them color and energy. Without these algae, corals starve. If temperatures don’t drop quickly, entire reefs die—and with them, the thousands of species that depend on reef ecosystems.

Warming also intensifies tropical cyclones. Hurricanes draw energy from warm ocean surfaces; hotter water means more fuel for storms. Hurricane Dorian (2019), Typhoon Haiyan (2013), and countless other catastrophic storms have links to elevated sea surface temperatures.

Even monsoon systems—the seasonal rains that billions depend on for agriculture—are destabilizing. Warmer oceans alter atmospheric moisture transport, making monsoons more erratic: sometimes too much rain causing floods, sometimes too little causing droughts. Food security across Asia and Africa hangs in the balance.

B. Acidification

When oceans absorb CO₂, it doesn’t just disappear—it triggers a chemical reaction that forms carbonic acid, lowering ocean pH. Since the Industrial Revolution, ocean pH has dropped by about 0.1 units, representing a 30% increase in acidity. That’s faster than any acidification event in the last 300 million years.

Ocean acidification is devastating for calcifying organisms—creatures that build shells and skeletons from calcium carbonate. Oysters, clams, sea urchins, and coral all struggle to form shells in acidic water. Some shellfish larvae dissolve before they even develop properly.

Pteropods—tiny sea snails that form massive swarms in polar waters—are already showing shell degradation. These creatures are a crucial food source for fish, seabirds, and whales. If pteropods collapse, entire Arctic and Antarctic food webs could follow.

The economic impact is real. Pacific Northwest oyster hatcheries have suffered massive die-offs linked to acidification. Shellfish industries worth billions face uncertain futures. Coral reefs—already battered by warming—face a double assault as acidification weakens their ability to rebuild damaged structures.

C. Deoxygenation

Warm water holds less dissolved oxygen than cold water—a basic chemistry principle with catastrophic implications. As oceans heat up, oxygen levels drop. Since 1960, the ocean has lost approximately 2% of its oxygen. That might not sound like much, but in ocean terms, it’s enormous.

Deoxygenation creates oxygen minimum zones (OMZs)—regions where dissolved oxygen falls so low that most marine life can’t survive. These “dead zones” are expanding in the open ocean and proliferating in coastal areas affected by nutrient pollution.

The Gulf of Mexico experiences a massive dead zone every summer, fueled by fertilizer runoff from Midwest farms. Nutrients trigger algal blooms; when algae die, bacteria consume them, depleting oxygen in the process. Fish flee or suffocate. Shrimp harvests plummet. Entire ecosystems shut down temporarily—or permanently.

Globally, over 500 coastal dead zones have been identified, affecting hundreds of thousands of square kilometers. Species that can’t escape these zones—bottom-dwelling fish, crabs, corals—simply die. Those that can flee lose habitat, concentrating in shrinking oxygen-rich refuges where competition intensifies.

Pollution & Human Impact — The Silent Ocean Crisis

Beyond climate change, the ocean is battling a massive influx of physical and chemical pollutants.

A. Plastic & Microplastic Pathways

Every year, an estimated 8-10 million tons of plastic enter the ocean. That’s roughly a garbage truck’s worth every minute. Rivers act as highways, carrying plastic waste from inland cities to coastal waters and eventually to the open ocean where currents accumulate it into massive gyres.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch—a swirling concentration of debris between Hawaii and California—covers an area twice the size of Texas. But visible plastic is only part of the problem. Microplastic pollution—fragments smaller than 5mm—has infiltrated every marine ecosystem from surface waters to the deepest trenches.

Microplastics enter food chains when small organisms mistake them for food. Fish consume them; seabirds feed them to chicks; filter feeders like mussels and oysters accumulate them in their tissues. Humans eating seafood now ingest an estimated 50,000 microplastic particles annually.

The health impacts remain uncertain, but the trajectory is clear: plastic production is accelerating, waste management isn’t keeping pace, and oceans are becoming permanent plastic repositories for centuries to come.

B. Chemical Pollution

Industrial chemicals, heavy metals, pesticides, and pharmaceutical residues flow into oceans through rivers, runoff, and direct discharge. Mercury accumulates in fish tissues, concentrating as it moves up food chains—a process called biomagnification. Large predators like tuna and swordfish can carry mercury levels dangerous for human consumption.

Oil spills make headlines, but chronic low-level petroleum pollution from shipping, drilling, and runoff causes more cumulative damage. Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) resist breakdown, cycling through ecosystems for decades, disrupting reproduction and immune systems in marine wildlife.

C. Noise Pollution

Oceans aren’t silent—they’re acoustic environments where animals rely on sound for communication, navigation, and hunting. Whales sing across ocean basins. Dolphins echolocate prey. Fish use sound to find mates and avoid predators.

But human activity has made oceans exponentially louder. Shipping traffic generates constant low-frequency noise. Seismic surveys for oil and gas blast sound waves that can travel hundreds of kilometers. Military sonar has been linked to whale strandings and hearing damage in marine mammals.

This acoustic smog disrupts behavior, communication, and migration patterns. Whales that can’t hear each other’s calls become isolated. Fish larvae that navigate by sound signals get lost. It’s an invisible form of habitat destruction with measurable biological consequences.

D. Overfishing & Illegal Fishing

Over one-third of global fish stocks are overfished—harvested faster than they can reproduce. Industrial trawlers drag nets across seafloors, destroying habitats and catching massive volumes of unintended species (bycatch) that are simply discarded dead.

Removing apex predators like sharks and tuna triggers trophic cascades—ecological chain reactions that ripple through entire ecosystems. Without top predators controlling prey populations, mid-level species explode, overconsuming their own food sources and destabilizing communities that evolved over millions of years.

Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing accounts for up to 30% of total catch in some regions. These operations ignore quotas, protected areas, and gear restrictions, undermining conservation efforts and stealing resources from communities that depend on them.

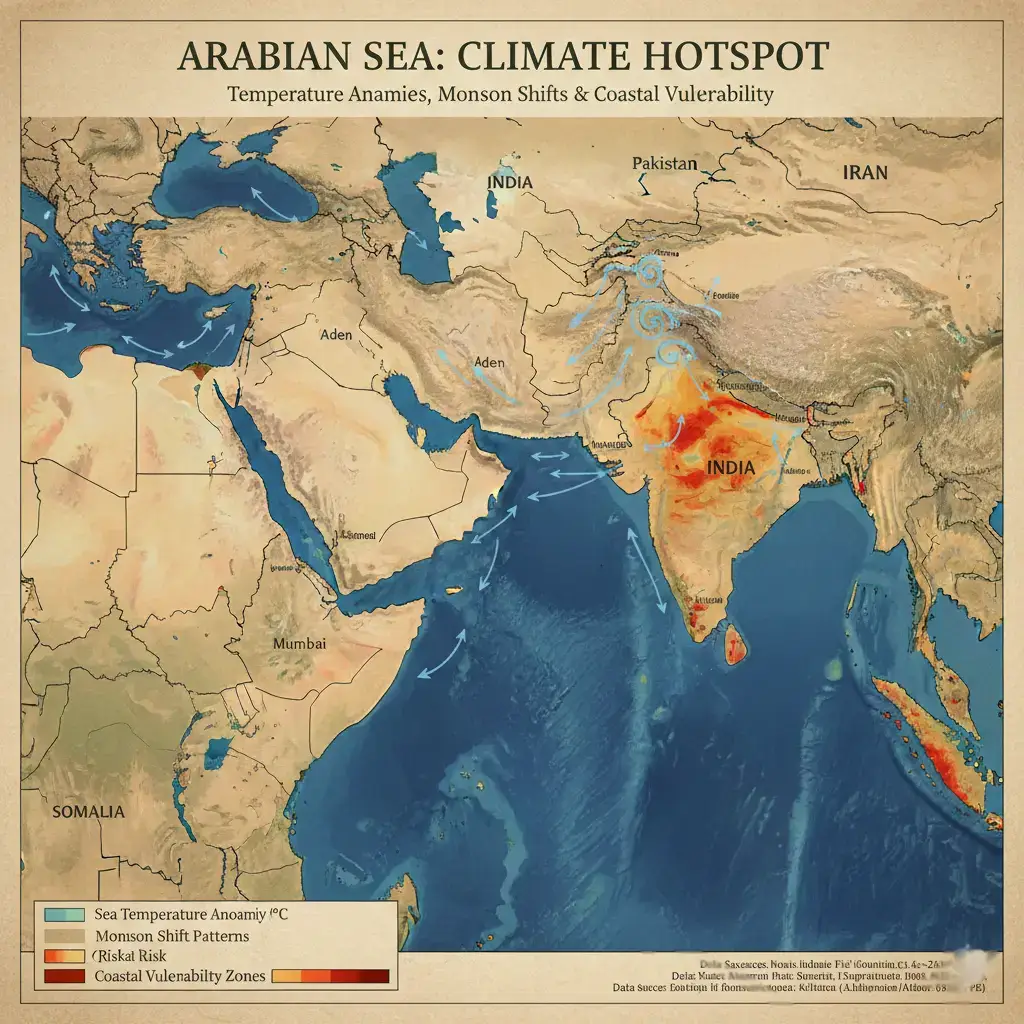

Regional Spotlight — Indian Ocean & Arabian Sea

While global ocean trends dominate headlines, regional hotspots reveal concentrated impacts that deserve urgent attention. The Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea exemplify how ocean changes hit hardest in regions least equipped to adapt.

The Arabian Sea is warming faster than almost any other ocean region—approximately 1.2-1.4°C over the past century. This isn’t just about hotter water; it’s reshaping the South Asian monsoon system that determines rainfall patterns for over a billion people across Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh.

Monsoon variability has intensified dramatically. Some years bring catastrophic flooding as atmospheric rivers dump months of rain in days. Other years see drought conditions that devastate agriculture. The 2022 Pakistan floods—which submerged one-third of the country—were linked to exceptionally warm Arabian Sea temperatures that supercharged moisture transport.

Coastal communities along Pakistan’s Makran coast and India’s western shore face multiple simultaneous threats: sea-level rise eroding shorelines, saltwater intrusion contaminating freshwater aquifers, and intensifying cyclones battering infrastructure. Cities like Karachi and Mumbai—home to tens of millions—sit directly in harm’s way.

Fisheries are shifting as species migrate toward cooler waters or deeper zones. Traditional fishing communities that have worked the same grounds for generations are finding catches declining or species compositions changing beyond recognition. Livelihood disruption translates directly into poverty and food insecurity.

The Indian Ocean also contains some of the world’s most important shipping lanes, carrying petroleum from the Middle East to Asia. Any disruption—from extreme weather to geopolitical conflict—reverberates through global energy markets.

This region exemplifies why ocean health isn’t just an environmental issue—it’s a security, economic, and humanitarian issue with implications far beyond coastlines.

Tipping Points — The Future We Must Avoid

Climate systems don’t change linearly—they have thresholds. Cross certain boundaries, and feedback loops trigger rapid, irreversible transformations. Ocean tipping points represent the difference between manageable change and catastrophic collapse.

Coral reef collapse is approaching critical mass. With global temperatures already 1.1°C above pre-industrial levels, coral reefs face near-constant bleaching stress. At 1.5°C warming, we lose 70-90% of reefs. At 2°C, over 99% disappear. We’re on track to cross 1.5°C within the next decade unless emissions plummet immediately.

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) shows concerning signs of weakening. Some models suggest we could hit a tipping point this century where the circulation collapses entirely—an event that would fundamentally reorganize Northern Hemisphere climate, potentially triggering rapid cooling in Europe while other regions overheat.

Blue carbon ecosystem decline accelerates warming in a vicious cycle. When mangroves, seagrasses, and marshes are destroyed, stored carbon releases back into the atmosphere. At the same time, we lose their carbon sequestration capacity, removing a crucial climate buffer.

Methane hydrates—frozen methane trapped in seafloor sediments—represent a nightmare scenario. Warming oceans could destabilize these deposits, releasing massive quantities of methane (a greenhouse gas 25 times more potent than CO₂) into the atmosphere. While probability remains debated, the potential for runaway warming makes this a risk we cannot ignore.

The next 30 years determine which trajectory we follow. Every fraction of a degree matters. Every ecosystem we protect buys time. Furthermore every delay makes recovery exponentially harder.

Science-Backed Solutions — What Actually Works

Protecting the ocean requires a multi-faceted approach focused on conservation, restoration, and policy reform.

A. Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

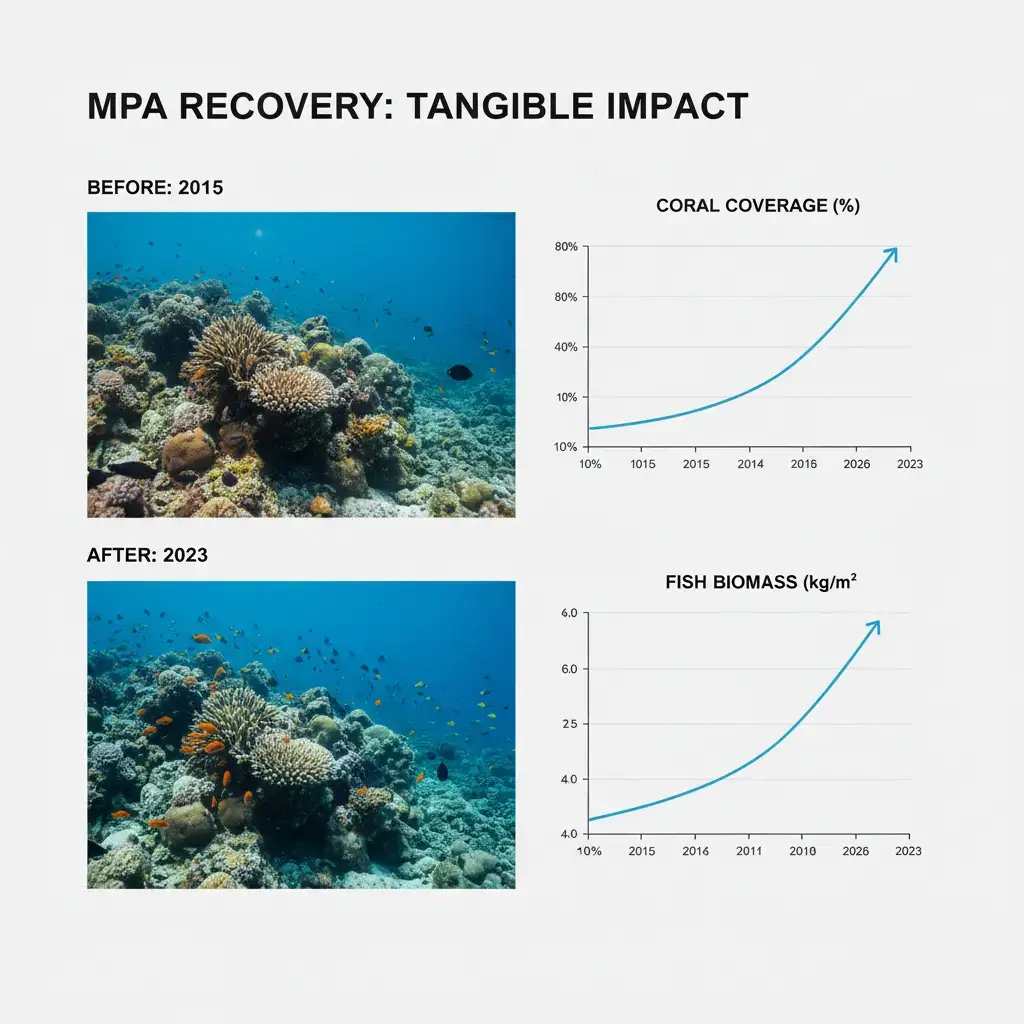

Marine protected areas work—when designed well and enforced properly. These designated zones restrict fishing, mining, and other extractive activities, giving ecosystems space to recover.

Studies show that well-managed MPAs increase fish biomass by an average of 400% within five years. Species diversity rebounds. Ecosystem functions restore. Benefits spill over into surrounding areas as fish populations expand beyond protection boundaries.

The global 30×30 target—protecting 30% of oceans by 2030—has gained momentum with over 100 nations committing. Currently, about 8% of oceans have some protection, but only 3% are fully protected from extractive activities. Closing that gap requires political will, funding, and community engagement.

Successful MPAs balance conservation with community needs. Locally managed marine areas (LMMAs) in the Pacific allow traditional fishing while restricting industrial operations, preserving both ecosystems and livelihoods.

B. Blue Carbon Restoration

Restoring mangroves, seagrass meadows, and salt marshes delivers triple benefits: carbon sequestration, biodiversity habitat, and coastal protection. These ecosystems store carbon up to 40 times faster per unit area than tropical forests.

Mangrove restoration projects in Indonesia, Kenya, and Madagascar have successfully replanted millions of trees, creating green barriers against storm surges while providing nursery habitat for commercially important fish species. Communities benefit economically while fighting climate change.

Seagrass restoration is more challenging but equally crucial. Projects in Virginia’s Chesapeake Bay have restored over 3,600 hectares of seagrass meadows, improving water quality and supporting fish populations. These restored meadows now sequester thousands of tons of carbon annually.

The carbon sequestration potential is massive: protecting and restoring blue carbon ecosystems could offset up to 1 billion tons of CO₂ annually—roughly equal to Japan’s total emissions.

C. Sustainable Fisheries

Sustainable fishing isn’t about stopping fishing—it’s about fishing smarter. Science-based quotas that match catch limits to reproduction rates allow stocks to replenish. Gear modifications reduce bycatch. Seasonal closures protect spawning periods.

Iceland’s cod fishery recovered from near-collapse through strict quotas and monitoring. Alaska’s salmon fisheries are managed sustainably, maintaining both healthy populations and profitable harvests. These examples prove that conservation and economic prosperity can coexist.

Community-based management, where local fishers participate in decision-making, shows particularly strong results. When communities have ownership and see direct benefits from healthy fish stocks, compliance improves and ecosystems recover.

D. Pollution Control

Plastic bans and reduction policies are spreading globally. Over 60 countries have banned single-use plastic bags. Extended producer responsibility laws make manufacturers responsible for product lifecycle management, incentivizing recyclable designs.

Wastewater treatment infrastructure prevents nutrient pollution that fuels dead zones. The European Union’s Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive has significantly reduced coastal pollution by requiring treatment before discharge.

Satellite monitoring and AI tracking systems now detect illegal fishing vessels, oil spills, and pollution sources in real-time. Global Fishing Watch uses satellite data to create transparency in ocean activities, helping enforcement agencies target illegal operations.

How Scientists Study the Ocean — Modern Tools & Tech

Understanding ocean health requires constant monitoring across vast distances. Modern ocean science combines cutting-edge technology with traditional observation methods to build comprehensive pictures of marine systems.

ARGO floats—autonomous drifting sensors—have revolutionized ocean monitoring. Over 4,000 floats drift with currents, diving to 2,000 meters every 10 days to measure temperature, salinity, and pressure before surfacing to transmit data via satellite. This global array provides real-time ocean interior data impossible to collect by ships alone.

Satellites monitor sea surface temperature, ocean color (indicating phytoplankton blooms), sea level rise, and even wave heights. The Sentinel and Landsat satellite programs provide free, continuous global ocean observations that inform climate models and fisheries management.

Deep-sea robotics—remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs)—explore regions too deep or dangerous for human divers. These submersibles map seafloors, sample hydrothermal vents, and document deep-sea ecosystems, revealing new species on nearly every expedition.

DNA barcoding and environmental DNA (eDNA) techniques allow scientists to identify species from water samples. Organisms constantly shed DNA into surrounding water; collecting and sequencing these samples reveals which species inhabit an area without seeing them directly. This technology accelerates biodiversity surveys and monitors endangered species non-invasively.

Citizen science projects engage the public in data collection. Reef Check trains volunteer divers to survey coral health. Secchi Disk studies use simple tools to measure water clarity globally. These programs democratize ocean science while collecting data across scales impossible for researchers alone.

The Road Ahead — Why Ocean Science Matters More Than Ever

The ocean isn’t just a passive victim of climate change—it’s humanity’s partner in climate stability, if we choose to treat it that way. Every investment in ocean science, conservation, and restoration multiplies returns through carbon sequestration, storm protection, food security, and biodiversity preservation.

We stand at a crossroads. Current trajectories lead toward collapsed fisheries, acidified dead zones, and coastlines abandoned to rising seas. Alternative paths—informed by science, driven by policy, supported by communities—lead toward resilient ecosystems that continue supporting life for generations.

The choice isn’t between economy and environment. Healthy oceans are the economy for billions of people. Climate resilience depends on functioning marine ecosystems. Future prosperity requires recognizing that human wellbeing and ocean health are inseparable.

This generation decides whether Earth remains the Blue Planet or becomes just another warm rock with empty seas. The science is clear. The solutions exist. What remains is action—collective, sustained, and immediate.

Conclusion

Earth’s oceans regulate climate through thermohaline circulation and carbon pumping, generate at least 50% of our oxygen via phytoplankton, and host the planet’s most biodiverse ecosystems from coral reefs to deep-sea vents.

Over 3 billion people depend directly on oceans for protein, while maritime industries generate trillions in economic activity. Yet oceans face unprecedented threats: warming waters triggering marine heatwaves and coral bleaching, acidification dissolving shells and skeletons, deoxygenation creating expanding dead zones, and pollution from plastics to chemicals degrading every marine environment.

Regional hotspots like the Arabian Sea demonstrate concentrated impacts—intensifying monsoon variability, accelerating sea-level rise, and disrupting fisheries that support millions. Tipping points loom: coral reef collapse, AMOC slowdown, and blue carbon ecosystem decline threaten irreversible changes.

Solutions exist and work: marine protected areas restore biodiversity, blue carbon ecosystems sequester carbon while protecting coasts, sustainable fisheries maintain both stocks and livelihoods, and modern monitoring technology enables science-driven management. The role of oceans in global biodiversity and climate stability makes their protection not just environmental—it’s existential.

Understanding why Earth’s oceans matter means recognizing they’re not separate from human civilization, they are the foundation supporting it. The next 30 years determine whether that foundation holds or crumbles.

Recommended Resources for Curious Minds

These resources offer deeper dives into the science and policy discussed above:

This book provides a compelling, science-backed exploration of the climate crisis and the profound role of ocean tipping points.

David Attenborough’s stunning visual journey through marine ecosystems brings ocean science to life with breathtaking cinematography and accessible explanations of ecological relationships.

Beautifully illustrated reference book covering everything from ocean formation to marine life to human impacts. Excellent for comprehensive understanding with stunning visuals.

While focused on freshwater, this award-winning book illustrates ecosystem disruption principles applicable to oceans, making complex environmental science compelling and accessible.

Transparency Note: Learning Breeze may earn a small commission from Amazon purchases made through these recommendations at no additional cost to you. We only recommend resources our editorial team has reviewed and believes add genuine educational value.

The Ocean’s Future Depends on What We Do Today

Share this article to spread ocean science awareness. Every person who understands why oceans matter becomes part of the solution.

Follow Learning Breeze for more science-backed deep dives into the topics shaping our planet’s future.