Millions of Americans are asking a question they never expected: “Is my DNA safe?” The 23andMe bankruptcy genetic data crisis has put personal information at risk in ways most people never imagined. Your genetic code, the most personal data you’ll ever share, might now be treated as just another asset in a bankruptcy sale.

Over 15 million people trusted 23andMe with their saliva samples. They wanted ancestry insights and health reports. What they got was uncertainty about who might own their genetic information tomorrow.

Here’s what you need to know right now. First, your DNA data is legally considered a company asset during bankruptcy. Second, it could be sold to buyers you never agreed to share with. Third, you have options to protect yourself, but you need to act quickly.

This guide walks you through everything. You’ll learn what happened, why it matters, and exactly what steps to take today. We’ll cover the legal protections (and gaps), how to remove your data permanently, and safer alternatives if you still want to contribute to genetic research.

Your genetic privacy deserves more than hope. It demands action.

What Happened: The 23andMe Bankruptcy Timeline and Its Impact on Your Genetic Data

The financial pressures on large DTC genetic testing companies have been mounting, driven by slowing consumer demand and high operating costs. Understanding the key events helps frame the current risk to your genetic testing information.

Filing for Chapter 11 & What That Means

23andMe filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in late 2024. This process helps struggling companies reorganize their debt while they keep running. But for consumers, it opens up a risky gray zone.

Under Chapter 11, a company’s assets — including customer genetic data — become items that can be sold or transferred. As a result, your consent form and privacy policy may no longer protect you. Bankruptcy courts can override those agreements if selling the data helps pay creditors.

The company says it will protect customer privacy during the proceedings. However, legal experts point out that promises made before bankruptcy don’t always hold up later. In the end, courts often prioritize creditor payments over customer preferences.

State Attorney Generals’ Warnings & Consumer Advisories

Multiple state attorneys general issued urgent warnings to 23andMe customers. For example, New York’s AG told users to download their data quickly and request account deletion. Similarly, Oregon’s AG raised concerns about whether 23andMe could still protect genetic privacy under U.S. standards.

These alerts weren’t just routine updates. Instead, they showed that state officials believed consumers faced real risks during the bankruptcy process. They specifically warned that 23andMe’s data could be weakened by privacy gaps or even sold to third parties.

Because of these concerns, several states launched investigations into how the company planned to manage customer information during bankruptcy. They are now examining whether 23andMe can legally sell genetic data despite earlier promises to protect it.

Potential Sale of Genetic Data Assets

Recent court filings show that 23andMe’s massive genetic database is one of the company’s most valuable assets. Potential buyers now include pharmaceutical companies, biotech firms, and even AI developers. Each group wants access to millions of genetic profiles for its own reasons.

As the case moves forward, the bankruptcy court will decide who gets to buy these assets and under what rules. However, things could go in very different directions. Some buyers may continue 23andMe’s current privacy standards, but others might use your data in ways you never agreed to. And because of the bankruptcy, there’s no promise that a new owner will respect the original privacy policy you signed up for.

| September 2024 | Board Members Resign | All independent board members resign citing disagreements over company direction. Stock price plummets as concerns about company viability emerge. | |

| October 2024 | Financial Crisis Deepens | 23andMe reports significant quarterly losses and announces workforce reductions. Company explores strategic alternatives including potential sale or merger. | |

| November 2024 | Chapter 11 Bankruptcy Filed | 23andMe files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. Customer genetic data officially classified as company asset subject to bankruptcy proceedings. | ⚠ High Risk Alert |

| December 2024 | State AG Warnings Issued | New York, Oregon, and multiple state attorneys general issue consumer advisories warning about genetic data risks. Investigations opened into data protection during bankruptcy. | ⚠ Official Warnings |

| NOW – Take Action | Consumer Action Window | Download your data, request account deletion, revoke research consent, and request sample destruction. Current privacy policy still in effect but time is limited. | ✓ Action Required |

| January 2025 | Asset Evaluation Period | Bankruptcy court evaluates company assets including genetic database. Potential buyers begin submitting proposals. Customer objections can still be filed during this phase. | |

| Q1-Q2 2025 (Projected) | Potential Data Sale Approved | Court may approve sale of genetic database to highest bidder. New owner takes control with potentially different privacy policies. Deletion requests may face new procedures or delays. | ⚠ Critical Deadline |

Why Genetic Data Matters in Bankruptcy

1. Genetic Data as a Valuable Asset

Your saliva sample carries huge value — just not in the way most people imagine. Companies aren’t only looking at your ancestry results. They’re looking at data that pharmaceutical firms and tech companies are willing to pay millions for.

23andMe collects several layers of information from every user. First, your raw genotype file includes hundreds of thousands of genetic markers. Then, their processed reports match those markers with health risks and ancestry insights. Finally, research datasets link your genetics with your survey answers about lifestyle and medical history.

Because of this layered structure, the data becomes extremely valuable for scientific work. Pharmaceutical companies use massive genetic databases to find out which groups respond best to specific drugs. Meanwhile, AI companies rely on diverse genetic data to train predictive health models. And population genomics researchers study these huge datasets to understand human evolution and disease trends.

On its own, one genetic profile might be worth only a few dollars. However, when you combine 15 million of them, the value skyrockets. That massive dataset is worth hundreds of millions — and the bankruptcy court knows it. So do the companies preparing to bid on it.

2. How Bankruptcy Law Treats Digital Data

Bankruptcy laws were never designed for the world of genetic testing. Today, courts still treat digital data like a physical asset that can be listed, priced, and sold. That means your raw DNA file gets the same legal treatment as office chairs, computers, or patents.

When a company goes bankrupt, asset transfers follow strict rules. The court brings in trustees whose job is to maximize how much money creditors can recover. So if selling a company’s entire genome database earns more than shutting everything down, the court will usually approve the sale. And honestly, customer complaints rarely stop this process.

The biggest risk comes after the data changes hands. A new owner can legally update the privacy policy and shift how your information is used. They might expand data-sharing rules, keep your data for longer, or loosen restrictions around third-party access. You might get a notification about these changes—but by that time, your DNA data is already in someone else’s control.

| Asset Type | Can Be Sold in Bankruptcy? | Customer Control After Sale | Privacy Protections | Typical Buyer Interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Equipment (computers, furniture) | ✅ Yes | None – fully transferred | None needed | Low – depreciated value |

| Real Estate (office buildings, land) | ✅ Yes | None – new owner controls | Property records public | Medium – market dependent |

| Intellectual Property (patents, trademarks) | ✅ Yes | None – rights transfer | Public patent databases | High – strategic value |

| Customer Email Lists | ✅ Yes | Limited – can unsubscribe | Minimal – CAN-SPAM Act | Medium – marketing value |

| Social Media Accounts (followers, content) | ⚠️ Maybe | Can delete individual accounts | Terms of service vary | Medium – brand value |

| Genetic Data (raw files, health reports) | ✅ Yes | Limited – can request deletion | Privacy policy (non-HIPAA) | Very High – research value |

| Financial Records (transaction history) | ✅ Yes | None after anonymization | Some state privacy laws | High – analytics value |

| Medical Records (HIPAA-covered) | ❌ No* | Full – patient owns records | Strong – HIPAA protections | N/A – legally restricted |

What “Delete My Data” Actually Means

1. Different Types of Data 23andMe Stores

Deleting your 23andMe account takes more than hitting a single button. The company stores your information in several different systems, and each one needs its own removal step.

First, your raw genotype file is the core of everything. It includes hundreds of thousands of genetic markers taken from your saliva sample and sits in their main database. Then, your health reports are kept somewhere else. These reports contain the interpretations of your genetic data, and they’re often stored separately from the raw file.

Beyond that, there are backup copies. Most companies rely on redundant systems for disaster recovery, so older versions of your data may remain in archived storage even after you ask for deletion. If you joined their research program, your information may also appear in independent research datasets used for ongoing studies, which makes things even more complicated.

Finally, there’s your physical saliva sample. It stays in storage unless you directly request its destruction. This step is different from deleting your digital data, and most users don’t even realize they need to ask for it.

2. Permanence & Limits of Deletion

True deletion isn’t instant, and it doesn’t cover everything. When you request to delete your account, 23andMe says it will remove your data within 30 days. However, this deadline applies only to the main databases that are currently in use.

Here’s what actually gets deleted: your account access, your raw genotype file stored in active systems, your processed health reports, and your link to genetic matches. Yet some things can stick around. Backup copies may stay for a set retention period. If you previously agreed to research studies, your de-identified research data can remain. Even your genetic matches may still appear in other users’ accounts until they sign in again and the system updates.

Experts point out some major gaps. De-identified data—information that removes your name and contact details—can stay in research databases for years, sometimes forever. Companies claim this data no longer counts as “yours” under privacy laws. But because re-identification techniques keep improving, skilled analysts could still connect it back to you.

Timing is especially important right now. If you request deletion during the bankruptcy process, the company must follow its current privacy policy. But if you wait, a future buyer could introduce new rules, slower timelines, or stricter limits on deletion.

Visual flow showing what happens to each type of data when you request deletion, with timelines and what remains in various systems: Download Here!

Legal & Regulatory Protections in the U.S.

1. Federal Protections

Two major U.S. laws shape how your genetic data is protected, but both leave big gaps—especially when a company like 23andMe faces bankruptcy.

First, there’s GINA, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act. This law stops health insurers and employers from using your DNA against you. It prevents health insurance companies from raising your premiums or denying your coverage because of your genetic risk. It also stops employers from using your DNA in hiring, firing, or promotions.

However, GINA doesn’t cover everything. It does not apply to life insurance, disability insurance, or long-term care insurance. These companies can still legally use your genetic information when deciding your rates or eligibility. Plus, GINA doesn’t control who can buy or sell your data—it only limits how certain groups can use it.

Then there’s HIPAA, the law that protects your medical records. But here’s the catch: HIPAA doesn’t apply to most direct-to-consumer DNA testing companies. It only covers data held by doctors, hospitals, insurance companies, and certain health systems. Because 23andMe is a consumer genetics company—not a medical provider—your DNA falls outside HIPAA’s protection. As a result, millions of genetic profiles don’t get the same safeguards given to traditional medical records.

2. State-Level Privacy Laws

Some states offer stronger protections than federal law. California’s genetic privacy laws require explicit consent before sharing genetic data. The state also gives consumers rights to know who accesses their information.

Recent AG advisories from New York and Oregon specifically addressed the 23andMe situation. They warned that state consumer protection laws might not prevent data sales during bankruptcy. State attorneys general can negotiate with bankruptcy courts for consumer protections, but they can’t unilaterally block asset sales.

A few states classify genetic information as personal property belonging to the individual, not the company. These laws might give customers stronger standing to object in bankruptcy court. But this legal territory remains largely untested. No major genetic testing bankruptcy has fully resolved these questions yet.

3. Ethical & Policy Risks

Beyond current laws, significant ethical risks emerge when genetic databases change hands. Re-identification poses the biggest technical threat. Even “de-identified” genetic data can potentially be linked back to individuals using publicly available information.

Third-party use creates policy risks. New owners might partner with data brokers, insurance companies, or government agencies in ways the original privacy policy prohibited. Each partnership expands how many entities can access your genetic information.

Future policy changes present the long-term risk. Today’s buyer might have acceptable privacy practices. But what happens when they face financial pressure? They might sell to another company with fewer scruples. Your genetic data could trade hands multiple times, moving further from the protections you originally agreed to.

State-by-State Genetic Privacy Protection Comparison

| State | Protection Level | Key Laws & Protections | Data Sale Restrictions | Consumer Rights | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| California | ★★★★★ Strong | California Genetic Information Privacy Act; CCPA/CPRA applies to genetic data | Requires explicit consent for sale; consumers can opt-out | Right to know, delete, opt-out; private right of action | Treats genetic data as sensitive personal information; strongest enforcement |

| Utah | ★★★★☆ Strong | Genetic Testing Privacy Act (2021) | Prohibits sale without explicit consent | Right to deletion; right to destruction of physical samples | Classifies genetic data as individual’s property |

| Florida | ★★★★☆ Strong | Florida Genetic Privacy Act | Genetic info cannot be sold without written consent | Right to sample destruction; right to know who accessed data | Includes criminal penalties for violations |

| New York | ★★★☆☆ Moderate | Civil Rights Law §79-l; SHIELD Act | Requires informed consent but limited sale restrictions | Data breach notification; some deletion rights | AG issued specific 23andMe advisories |

| Oregon | ★★★☆☆ Moderate | Genetic Privacy Law | Consent required for testing; limited sale restrictions | Right to test results; limited deletion rights | AG issued 23andMe consumer warnings |

| Texas | ★★★☆☆ Moderate | Consent for genetic testing required | Some restrictions on insurance use; weak sale restrictions | Limited rights; must consent to testing | Focuses more on testing consent than data protection |

| Alaska | ★★★☆☆ Moderate | Genetic privacy statute | Insurance discrimination prohibited | Basic notification rights | Minimal enforcement mechanisms |

| Illinois | ★★☆☆☆ Limited | Biometric Information Privacy Act (limited genetic coverage) | Not specifically addressed | Some biometric protections may apply | BIPA primarily covers fingerprints, not full genetic data |

| Georgia | ★★☆☆☆ Limited | Limited genetic testing regulations | No specific restrictions on data sale | Minimal consumer rights | Relies primarily on federal GINA protections |

| Alabama | ★☆☆☆☆ Weak | No state-specific genetic privacy law | No restrictions beyond federal law | Only federal rights apply | No state-level protections or enforcement |

| Wyoming | ★☆☆☆☆ Weak | No state-specific genetic privacy law | No state restrictions | Federal protections only | No AG guidance on genetic testing |

Step-by-Step Action Plan for Users After the 23andMe Bankruptcy to Protect Their Genetic Data

1. Immediate Actions You Should Take

Time matters. Taking these four steps now protects your genetic data before bankruptcy proceedings conclude. Each action serves a specific purpose in securing your information.

Download Your Raw DNA Data and Reports (How-To)

Your raw data belongs to you. Download it now before any ownership transfer limits access. Here’s exactly how to do it:

Log into your 23andMe account using a secure internet connection. Navigate to your account settings—look for the gear icon in the upper right corner. Select “Download Data” or “Browse Raw Data” depending on your account type. Click “Submit Request” for your raw genetic data file.

23andMe will email you when your file is ready, usually within 24 hours. Download the file immediately and save it to multiple secure locations: your computer, an encrypted external drive, and a secure cloud storage service. The file format is typically a text file containing your genetic markers.

Also download all your health reports and ancestry information. Use your browser’s print-to-PDF function to save each report. These documents might become inaccessible after your account deletion.

Revoke Research Consent (Template Email)

If you previously consented to research, revoke that permission immediately. This prevents your genetic data from being used in future studies under new ownership.

Email Template:

Subject: Immediate Revocation of Research Consent – Account [Your Account Number]

To Whom It May Concern:

I am writing to immediately revoke all research consent previously granted for my 23andMe account. This includes consent for:

- General research participation

- Individual study participation

- Sharing with third-party researchers

- Use in future research projects

Please confirm in writing that:

- My genetic data will be removed from all research databases

- No further research use of my information will occur

- The revocation is effective immediately

Account Email: [Your email] Account Number: [If available] Name on Account: [Your full name]

I request written confirmation of this revocation within 14 days.

Sincerely, [Your name]

Send this email to 23andMe’s customer service address. Keep a copy with the date sent for your records.

Request Permanent Deletion of Your Account & Data (Template)

Account deletion requires explicit action. Simply revoking research consent doesn’t delete your data from 23andMe’s primary databases.

Deletion Request Template:

Subject: Urgent Request for Complete Account and Data Deletion

To 23andMe Customer Service:

I request immediate and permanent deletion of all data associated with my account, including:

- Raw genotype data

- All health and ancestry reports

- All derivative data and analysis

- Profile information and survey responses

- All backup and archival copies

- Connection to genetic relatives

I understand this action is permanent and irreversible.

Please confirm in writing:

- The date deletion will be completed

- Which data will be permanently removed

- Whether any data will be retained and why

- Whether my data was included in any bankruptcy asset inventories

Account Email: [Your email] Name: [Your full name]

I expect completion within the 30-day timeline stated in your privacy policy.

Sincerely, [Your name]

Ask for Your Saliva/Sample Destruction (Template + How to Find the Request Form)

Your physical saliva sample requires separate destruction request. Many customers forget this critical step.

Check 23andMe’s current privacy policy for their sample destruction request process. Look for sections titled “Biobanking” or “Sample Storage.” Some accounts may have a request form in account settings under “Sample Storage Options.”

Sample Destruction Template:

Subject: Request for Physical Sample Destruction – Account [Your Account Number]

To 23andMe Sample Storage Department:

I request immediate destruction of my physical saliva sample currently stored by 23andMe or any affiliated biobank facility.

Please confirm:

- Current location of my sample

- Destruction method to be used

- Expected destruction date

- Written confirmation when destruction is complete

Account Email: [Your email] Name on Account: [Your full name] Sample Barcode: [If available on your kit]

I request completion within 30 days and written verification of destruction.

Sincerely, [Your name]

2. Additional Data-Security Best Practices

Beyond immediate deletion requests, these security measures protect your account during the transition period.

Change your account password to a unique, strong password you don’t use elsewhere. Use a password manager to generate a complex password with at least 16 characters mixing letters, numbers, and symbols. Enable two-factor authentication if available. This prevents unauthorized access to your account during bankruptcy proceedings.

Monitor privacy policy updates carefully. Companies must notify customers of policy changes, but these notices often arrive as easy-to-miss emails. Set up email filters to flag any messages from 23andMe. Read every policy update to understand how your data handling might change.

Watch for bankruptcy court notifications. If you want to formally object to data sales, you may need to file objections with the bankruptcy court. Visit the bankruptcy court’s public docket system to monitor case developments. Some consumer advocacy groups also track these cases and send alerts.

How the 23andMe Bankruptcy Genetic Data Fallout Increases Risks to Relatives and Law Enforcement Access

How Your DNA Can Implicate Relatives

Your genetic privacy decision affects more than just you. DNA testing creates a web of connections that extends to relatives who never consented to genetic testing at all.

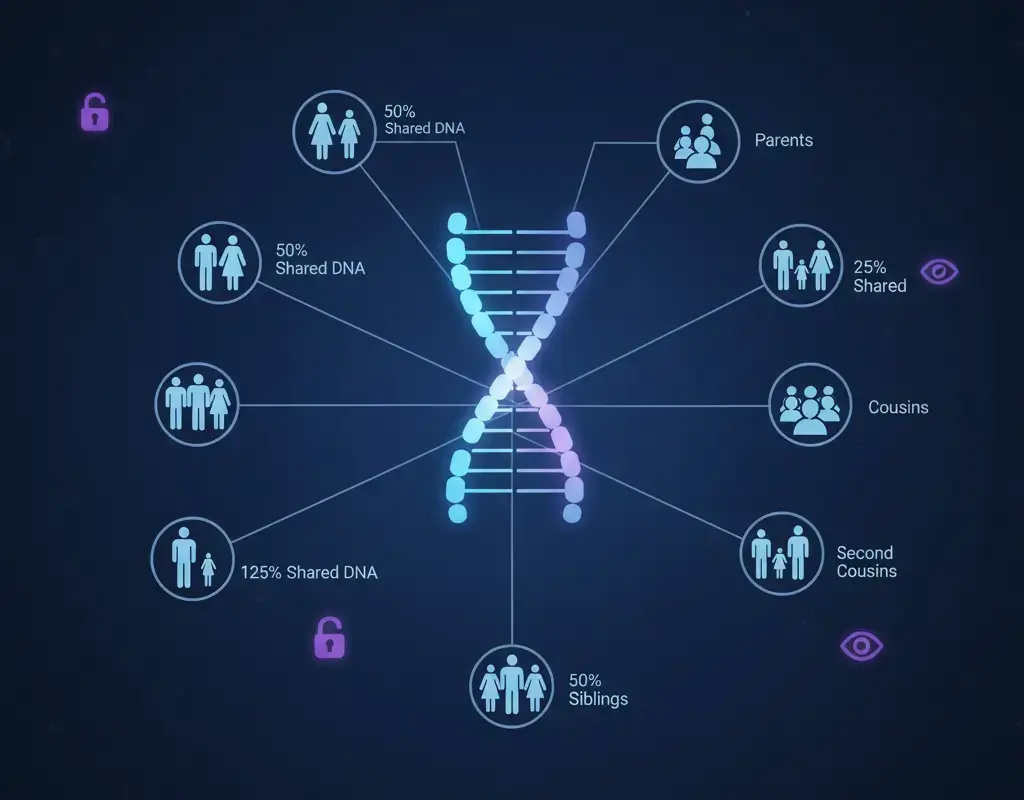

Genetic match features connect your profile to relatives in the database. These connections reveal family relationships even between distant cousins. If you tested but your sibling didn’t, your DNA still exposes information about their genetic makeup. Siblings share approximately 50% of their DNA, first cousins share 12.5%, and the connections extend outward through your entire family tree.

Law enforcement increasingly uses genealogical databases to investigate crimes. While 23andMe has resisted most law enforcement requests, future owners might have different policies. Police have successfully used other genetic databases to identify suspects through their relatives’ DNA. Your genetic information could theoretically help identify a relative involved in a crime—even a relative you’ve never met.

This creates an ethical dilemma. You can’t delete your relatives’ genetic signature from your own DNA. Even after you delete your account, the genetic information you shared has already helped map your family tree in ways that might persist in aggregate research data.

What Happens After Deletion for Your Family’s Data (and Yours)

Deletion removes your profile, but genetic matches have limits. When you delete your account, you disappear from other users’ match lists the next time they log in. But screenshots or notes they took about your connection don’t automatically vanish.

Research datasets present a bigger challenge. If you participated in research before deletion, your genetic data might remain in scientific studies as de-identified information. Your family connections might persist in population genetics research even after individual accounts are removed. Scientists studying hereditary disease patterns often keep family relationship data separate from identifying information.

Talk with relatives who also tested. Explain the bankruptcy situation and its implications for family genetic privacy. Consider suggesting they also download their data and evaluate deletion. Remember that each family member controls only their own account—you can’t delete relatives’ data, only inform them of risks.

Some families decide together whether to maintain genetic testing presence or collectively delete accounts. This conversation is personal and depends on your family’s privacy preferences and concerns about future data use.

Who Would Want to Buy 23andMe’s Data — And Why

Potential Buyers and Use Cases

The genetic database holds different value for different buyers. Understanding their motivations helps you assess risks from various ownership scenarios.

Pharmaceutical companies lead the list of interested parties. They use genetic databases to identify drug targets and understand which populations benefit most from specific treatments. A database of 15 million genetic profiles linked to health surveys provides insights worth hundreds of millions for drug development. Companies working on rare disease treatments particularly value diverse genetic data showing disease prevalence across populations.

AI and biotech firms need massive datasets to train predictive algorithms. Machine learning models that predict disease risk, drug responses, or even aging patterns require millions of examples to achieve accuracy. Your genetic data becomes training material for artificial intelligence systems. These companies might pay premium prices for well-organized genetic data with linked health outcomes.

Academic research institutions represent potentially more trustworthy buyers. Universities and research hospitals could use the database for population genomics studies and medical research. They typically operate under stricter ethical guidelines than commercial entities. However, academic institutions also face financial pressures that might influence how they manage and share genetic data.

Risks & Benefits of Data Transfer

New ownership creates trade-offs worth understanding. Research benefits exist—genetic databases have contributed to important medical discoveries about disease prevention and treatment. Larger databases enable more powerful research that can help millions of people.

But privacy trade-offs come with those benefits. Commercial entities prioritize profit over privacy. Pharmaceutical companies might use genetic insights to develop expensive personalized treatments accessible only to wealthy patients. AI companies might build predictive models that insurance companies or employers later purchase for screening purposes.

Re-identification risk increases with each data transfer. New owners might combine your genetic data with other datasets they control, making it easier to identify individuals despite de-identification attempts. Data brokers specialize in linking supposedly anonymous information back to real people. Your genetic markers might be cross-referenced with public records, consumer purchase data, or social media information.

Policy changes after sale represent the most unpredictable risk. New owners can modify privacy policies within legal boundaries. They might introduce data sharing arrangements with partners you would never approve. Each subsequent owner in a chain of sales might weaken protections further. Your data could end up somewhere completely unrelated to health or ancestry research—perhaps in marketing databases or financial risk models.

Who Wants to Buy Your Genetic Data and Why

| Buyer Type | Primary Intended Uses | Privacy Risks | Potential Benefits to Science | Trust Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Companies | 1. Drug target identification 2. Clinical trial recruitment 3. Personalized medicine development 4. Treatment response prediction | HIGH • May share with insurance partners • Focus on profitable diseases only • Data could inform pricing strategies • Limited transparency on data handling | MODERATE-HIGH • Accelerates drug development • Improves treatment effectiveness • Advances rare disease research | ⚠️ Medium |

| AI/Biotech Firms | 1. Machine learning model training 2. Predictive health algorithms 3. Genetic screening tools 4. Consumer health apps | VERY HIGH • May combine with other datasets • Algorithm bias risks • Potential sale to data brokers • Unclear retention policies | LOW-MODERATE • Advances AI healthcare tools • May improve diagnostic accuracy • Limited peer-reviewed research | ⚠️ Low |

| Academic Research Institutions | 1. Population genomics studies 2. Disease mechanism research 3. Epidemiological analysis 4. Medical education | LOW-MODERATE • Strict IRB oversight • Published ethical guidelines • Transparent research protocols • Limited commercial sharing | HIGH • Peer-reviewed discoveries • Open science contributions • Public health improvements • Educational advancement | ✓ High |

| Data Brokers/Aggregators | 1. Consumer profiling 2. Cross-database linking 3. Marketing insights 4. Re-selling to multiple buyers | EXTREMELY HIGH • No research mission • Minimal regulation • Unknown end-use scenarios • High re-identification risk | NONE • No scientific contribution • Purely commercial exploitation • Undermines research trust | ✗ Very Low |

| Insurance Tech Companies | 1. Risk assessment models 2. Actuarial analysis 3. Product development 4. Underwriting automation | VERY HIGH • Could impact coverage/pricing • GINA doesn’t cover all insurance • Algorithmic discrimination risk • Limited consumer recourse | MINIMAL • May reduce fraud • Could improve risk accuracy • No direct research benefit | ✗ Low |

Alternatives: Safer Ways to Contribute Your DNA (If You Still Want to Share)

Academic / Non-Commercial Biobanks

Genetic research doesn’t require commercial companies. Academic and non-profit biobanks offer more transparent, ethically grounded alternatives for people who want to contribute to science.

Trusted research biobanks operate through universities and medical research centers. The All of Us Research Program run by the National Institutes of Health collects genetic and health data from diverse participants. UK Biobank, though focused on British residents, models best practices for genetic research databases. These institutions follow strict ethical guidelines and institutional review board oversight.

Look for biobanks with these characteristics: non-profit status, university or government affiliation, published ethical guidelines, participant advisory boards, and transparent data use policies. Check whether they allow participants to withdraw consent and request data deletion even after contributing to research.

Informed consent models vary between biobanks. Dynamic consent systems let participants adjust their preferences over time, choosing which types of research to support. Broad consent grants permission for many research uses but within ethical boundaries defined upfront. Both models offer more transparency than typical commercial genetic testing consent forms.

Consumer Alternatives

Some genetic testing companies take your privacy way more seriously than others. So it’s smart to research each company before you send your saliva to anyone.

A few signs show whether a company actually protects your data. For example, strong services offer clear data-deletion steps and ask for your permission before sharing your information for research. They also avoid selling your data to third parties, publish transparent yearly privacy reports, and earn certifications from independent privacy groups. Some companies even let you view your results and then delete your raw data from their servers right away.

Companies that allow data export also give you more control. Many services now offer genetic reports without keeping your information long-term. You simply upload your raw DNA file from another company, get your results, download your data, and request deletion. This approach keeps your sensitive information on their servers for the shortest time possible.

Meanwhile, a few companies have introduced “privacy-first” options. In these setups, your genetic analysis happens through encrypted computation, meaning your raw data never leaves your possession in an unencrypted form. These tools usually cost more, but they offer stronger protection.

Before you pick any genetic testing service, always check independent reviews. Groups like the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Consumer Reports regularly publish privacy evaluations. Their reports can help you spot companies with real privacy standards — and avoid those that rely on impressive marketing but weak policies.

Conclusion

The 23andMe bankruptcy exposes a truth many customers never considered: your genetic data was never fully yours to control. Privacy policies protect you only until financial pressure overwhelms those promises. Bankruptcy transforms personal information into corporate assets subject to sale.

But you still have power. Download your genetic data and reports today—they’re yours regardless of what happens to the company. Submit deletion requests for your account, research participation, and physical sample. These actions protect your genetic privacy before ownership changes create new uncertainties.

Understand the limitations of your actions too. Deletion removes most data but might not erase everything, especially information already in research databases. Your genetic privacy connects to relatives who may choose differently than you. Future genetic testing needs careful company selection prioritizing privacy over convenience.

Stay informed about bankruptcy proceedings through your state attorney general’s office. Monitor developments and consider joining consumer advocacy efforts if the court considers particularly concerning data sales. Your voice matters in how courts handle genetic data in bankruptcy.

Genetic research holds tremendous promise for medicine and science. But that promise shouldn’t require surrendering permanent control of your most personal information. Demand better protections, support privacy-focused alternatives, and hold companies accountable for safeguarding the genetic data they collect.

Frequently Asked Questions about 23andMe Bankruptcy Genetic Data

Yes. The company has faced significant financial pressures due to slowing consumer growth and high operational costs, leading to speculation and concerns about potential bankruptcy proceedings or a major corporate restructuring. This financial instability is the core reason for the current concerns over the safety of the genetic data asset.

While Chapter 11 bankruptcy is a reorganization process designed to help a company survive, there is no guarantee. Survival depends on the company successfully restructuring its debt, finding new investment, and potentially selling off non-core assets. The outcome remains uncertain, leading to the urgency in safeguarding your data now.

Yes, federal law and most privacy policies require the company to notify users of any sale or transfer of assets that includes personal information. However, the notification method (often email) may be easy to overlook.

No. Once your data has been used to create an aggregated, de-identified dataset for pharmaceutical research, it is nearly impossible to pull it back out of that data pool.

Data portability is your consumer right to receive a copy of your personal data (like your raw genotype file) in a usable format, which is why downloading your data now is so important.

Recommended Resources for Curious Minds

For those seeking to deepen their understanding of data privacy and genomics, these resources offer valuable insights:

- The Gene: An Intimate History by Siddhartha Mukherjee

- The Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race by Walter Isaacson

- Genetics 101: From Chromosomes and the Double Helix to Cloning and DNA Tests, Everything You Need to Know about Genes by Beth Skwarecki

- Privacy in the Age of Big Data: Recognizing Threats, Defending Your Rights, and Protecting Your Family by Theresa Payton

- Who Owns You? Science, Innovation, and the Gene Patent Wars by David Koepsell

Further Reading / Scientific References

- Gymrek et al., Science (2018): Re-identification risks.

- NIH All of Us Privacy Policy.

- California AG Genetic Privacy Advisory

- 23andMe Sample Destruction Form

- Bankruptcy Court Docket