Named Entity Recognition (NER) is one of the most important steps in natural language processing because it helps machines to identify people, places, and things inside the raw text. It is the first step that makes unstructured writing useful for search engines, AI models, and scientific applications. When someone says, “Google uses AI to understand your queries,” a huge part of that understanding is powered by NER.

Imagine reading this sentence:

“On 12 March 2024, Elon Musk announced that xAI raised $6 billion from Sequoia Capital in San Francisco.”

Your brain instantly knows Elon Musk is a person, xAI and Sequoia Capital are organizations, San Francisco is a location, 12 March 2024 is a date, and $6 billion is money. Named Entity Recognition is a component of natural language processing. It teaches machines to spot and classify the “who, where, when, and how much” in any piece of text. This process is automatic and can be done at scale.

Historically, the goal of early NLP was simply to understand grammar. With NER, the focus shifted to understanding meaning and context. This shift allowed machines to move beyond syntax and truly grasp the semantic content of a document. This shift kickstarted the utility of text processing that we rely on today.

In this monster guide, you’ll learn everything from the 1990s roots of NER to training your own transformer model on Urdu tweets in 2025. Let’s go.

Why Named Entity Recognition Matters in Modern Science and Technology

Named Entity Recognition is not just a cool research idea anymore, it is actively changing how we pull meaning from our massive stream of text data. And as we dig deeper, we can clearly see how NER is creating a practical impact across many fields.

1. Scientific Literature Mining

Every year, scientists publish more than 3 million research papers. That’s way too much for any human to keep up with—especially in fields like healthcare, genomics, or ecology. This is where NER steps in. It quickly scans thousands of papers and picks out key information such as disease names, gene sequences, protein interactions, chemical compounds, and treatment protocols.

Imagine a cancer researcher studying BRCA1 gene mutations. Instead of reading dozens of papers, an NER system can do the job in a few hours. It extracts every mention of BRCA1, the proteins linked to it, patient details, treatment outcomes, and even clinical trial findings. As a result, the researcher gets a clearer view, and faster. This speed matters because it connects insights that would take months—or even years—to uncover manually.

In ecology and environmental science, NER plays a similar role. It tracks species names, habitat details, climate data, and biodiversity signals across reports and databases. So, when a new invasive species appears, NER can immediately scan old records, map how it spread, and even hint at what might happen next.

2. Environmental Data Extraction from Field Reports

Climate scientists and environmental agencies handle huge amounts of unstructured data like field reports, sensor logs, news articles, and policy documents. Named Entity Recognition systems help by pulling out key details like pollution levels, locations, species names, weather events, and regulations.

For example, monitoring deforestation involves analyzing satellite data, news updates, government reports, and NGO field notes. NER spots important information such as place names, incident dates, responsible organizations, and affected regions. This creates a clear, complete picture that guides effective conservation strategies.

3. Government, Policy, and Research Papers

Policymakers and government agencies rely on NER to make sense of legislation, track compliance, and gauge public opinion. For example, when a new environmental regulation is proposed, NER can scan thousands of public comments. It can quickly spot stakeholder organizations, affected industries, regions, and key concerns.

Legal professionals also benefit from NER. It helps them to review contracts efficiently, highlighting parties, dates, monetary amounts, and jurisdiction details. Similarly, in financial services, NER supports compliance checks, fraud detection, and risk assessment. By tracking company names, transaction amounts, and regulatory issues across news feeds and filings, it makes complex data easier to manage.

4. Why NER Is Booming With AI

The rise of transformer models like BERT and RoBERTa has completely changed how NER works. Modern machine learning models can now reach accuracy levels above 90% on standard tests—almost matching humans. They understand context in ways older systems never could, telling apart “Apple the company” from “apple the fruit” just by looking at surrounding words.

Large language models have also made NER easier to use. Pre-trained models can be quickly fine-tuned for specific industries with small datasets. This has opened doors for companies of all sizes, letting them harness NER to make smarter decisions and use data more effectively.

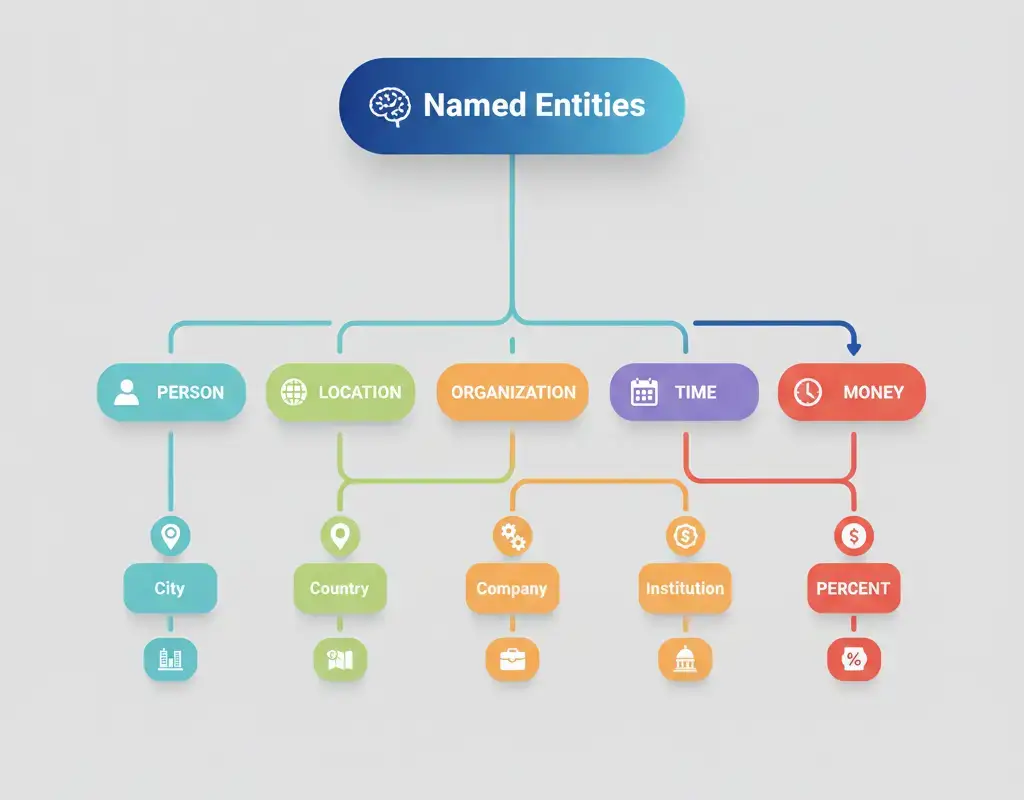

What Counts as an Entity? The Full Taxonomy

Not all words are created equal. Named Entity Recognition focuses on specific categories that carry real-world significance. Understanding entity types is crucial for building effective NER systems.

Common Entity Types

The most widely recognized entity types come from the original MUC and CoNLL shared tasks:

PERSON: Individual names like “Marie Curie,” “Elon Musk,” or “Dr. Sarah Johnson.” This includes full names, first names in context, titles, and nicknames.

ORGANIZATION (ORG): Companies, institutions, government bodies, and non-profits. Examples include “Microsoft,” “Stanford University,” “European Union,” and “Red Cross.”

LOCATION (LOC): Geographic entities ranging from cities and countries to rivers and mountains. “Tokyo,” “Amazon River,” “Mount Everest,” and “Silicon Valley” all qualify.

DATE: Temporal expressions including absolute dates (“January 15, 2024”), relative references (“next Tuesday,” “last quarter”), and time periods (“the 1990s,” “summer”).

TIME: Specific times like “3:30 PM,” “noon,” or “midnight.”

MONEY: Monetary amounts such as “$50 million,” “€120,” or “fifteen dollars.”

PERCENT: Percentage values like “25%” or “three-quarters.”

QUANTITY: Measurements and quantities including “50 kilograms,” “two dozen,” or “5 meters.”

Fine-Grained and Domain-Specific Categories

General entity types work for news articles and everyday text, but specialized domains require more granular classification. Healthcare NER systems recognize:

- DISEASE: “Type 2 diabetes,” “COVID-19,” “malaria”

- DRUG: “aspirin,” “Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine,” “chemotherapy”

- SYMPTOM: “fever,” “chest pain,” “fatigue”

- ANATOMY: “heart,” “prefrontal cortex,” “femur”

- GENE/PROTEIN: “BRCA1,” “hemoglobin,” “insulin receptor”

Legal NER includes entity types like STATUTE, COURT, CASE_NUMBER, and LEGAL_PRINCIPLE. Financial systems track STOCK_SYMBOL, EXCHANGE, FISCAL_PERIOD, and CREDIT_RATING. Each domain develops taxonomies matching its unique information needs.

Nested Entities and Overlapping Structures

Practical text rarely follows neat boundaries. Consider “The University of California, Berkeley’s Department of Computer Science.” This contains multiple nested entities:

- “University of California, Berkeley” (ORGANIZATION)

- “California” (LOCATION – nested within the organization)

- “Department of Computer Science” (ORGANIZATION – nested within the larger organization)

Nested NER handles these hierarchical relationships, recognizing that entities can contain other entities. This becomes especially important in scientific text where complex noun phrases carry multiple layers of meaning.

Overlapping entities present another challenge. In “New York-based analyst,” should the system mark “New York” as a location, “New York-based” as a modifier, or both? Different annotation guidelines make different choices, and models must be trained accordingly.

Why Entity Boundaries Are Challenging

Determining where an entity begins and ends tests even sophisticated models. Consider these examples:

- “President Biden” vs “President Joe Biden” vs “President” vs “Joe Biden”

- “COVID-19” vs “COVID-19” vs “coronavirus” vs “SARS-CoV-2”

- “New York” vs “New York City” vs “NYC”

Abbreviations, acronyms, aliases, and informal names create ambiguity. Context matters enormously. “JFK” might refer to John F. Kennedy, the airport, or a school depending on surrounding text. Token classification models must learn these subtle distinctions through exposure to diverse training examples.

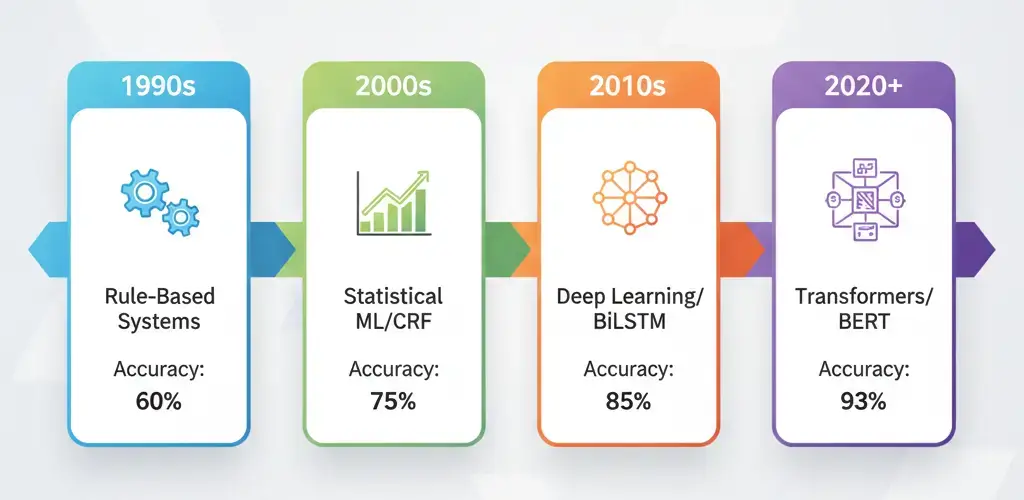

How Named Entity Recognition Works: The Core Approaches

Named Entity Recognition has evolved through several technological generations, each building on previous insights. Understanding these approaches helps you choose the right tool for your specific needs.

1. Rule-Based & Pattern-Based Systems (Old School but Useful)

The earliest NER systems relied on hand-crafted rules and regular expressions. These systems use pattern matching to identify entities:

- Capitalization patterns (words starting with capital letters are often names)

- Prefix/suffix indicators (words ending in “Corp” or “Inc” suggest organizations)

- Gazetteer lookups (dictionaries of known entity names)

- Contextual rules (words following “Dr.” are likely person names)

Pros: Rule-based systems are transparent, require no training data, and work perfectly for their designed patterns. They’re fast, interpretable, and easily customizable. For highly structured text with predictable formats (like extracting phone numbers or email addresses), rules remain unbeatable.

Cons: Rules don’t generalize. Each new pattern requires manual coding. They struggle with ambiguity, unseen entities, and creative language. Maintaining rule bases becomes nightmarish as coverage expands. A rule-based system might catch “Dr. Smith” but miss “Smith, MD” or “Jane Smith, physician.”

Examples: Many production systems still use rule-based components for specific tasks. Email parsing, invoice processing, and form extraction often combine rules with machine learning. A hybrid approach applies rules for obvious cases and reserves machine learning for ambiguous situations.

2. Statistical Machine Learning (CRF, HMM, MaxEnt)

The next generation brought statistical models that learn patterns from annotated training data. These feature-based models treat NER as a sequence labeling problem.

Conditional Random Fields (CRFs) dominated NER for over a decade. CRFs model the probability of entire label sequences, capturing dependencies between adjacent tags. If “New” is tagged as B-LOC (beginning of location), “York” is more likely to be I-LOC (inside location) than a separate entity.

CRF models use hand-engineered features:

- Word shape (capitalization patterns, digits, punctuation)

- Linguistic features (part-of-speech tags, syntactic chunks)

- Context windows (surrounding words)

- Gazetteer matching (presence in known entity lists)

- Word embeddings (pre-trained word vectors)

Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) and Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt) classifiers offered alternative approaches with similar feature engineering requirements.

Why CRFs Remain Important: CRFs are fast, require modest computing resources, and work well with limited training data. For production systems with tight latency requirements or when running on edge devices, CRFs still compete effectively. Many deployed NER systems in industry combine CRF efficiency with neural network accuracy.

The main limitation? Feature engineering requires domain expertise and manual effort. Features that work for news text fail in medical records or social media posts.

3. Deep Learning (BiLSTM-CRF)

Neural networks eliminated manual feature engineering by learning representations directly from text. The BiLSTM-CRF architecture became the deep learning standard for NER.

How It Works: Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory networks process text in both directions, capturing context from past and future words. The forward LSTM reads “New York City” left-to-right while the backward LSTM reads right-to-left, creating rich contextual embeddings that capture meaning from both directions.

These contextual embeddings feed into a CRF layer that predicts entity labels while enforcing valid tag sequences. The CRF prevents impossible transitions like B-PER followed by I-ORG (beginning of person name followed by inside organization), learning valid patterns from training data.

Character-Level Embeddings: BiLSTM-CRF models often include character-level processing using CNN or LSTM layers. This captures morphological patterns—prefixes, suffixes, and internal structure—helping with unknown words and misspellings. The model learns that words ending in “-ology” might be scientific terms or that “Mc” at the start suggests Scottish surnames.

BiLSTM-CRF models significantly outperformed CRFs on standard benchmarks, achieving 5-10 point F1 score improvements. They generalize better to unseen entities and handle ambiguity more gracefully. The trade-off is computational cost and larger training data requirements.

4. Transformers & Modern NER (BERT, RoBERTa, GPT Models)

The transformer revolution changed everything. Models like BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) use self-attention mechanisms to create deeply contextualized word representations.

Token Classification Explained Simply: BERT processes entire sentences simultaneously, with each word attending to every other word through multiple attention layers. The word “Apple” develops different representations in “Apple tastes sweet” versus “Apple released new iPhones” because attention weights capture surrounding context.

For NER, we add a classification layer on top of BERT’s output embeddings. Each token receives a label (B-PER, I-ORG, O for outside any entity, etc.). Fine-tuning adjusts BERT’s pre-trained knowledge to your specific entity types and domain.

Span-Based NER and Why It’s Rising: Traditional token classification has a problem—it forces the model to label each token independently, then reconstructs entities from adjacent tags. Span-based approaches directly predict entity boundaries.

These models enumerate all possible text spans up to some maximum length, then classify each span as an entity type or “not an entity.” This naturally handles entities of any length and avoids invalid tag sequences. Span-based models excel at nested entity recognition since multiple overlapping spans can be labeled simultaneously.

Nested NER Techniques: Transformers enable sophisticated architectures for nested entities:

- Multi-layer prediction: Separate classification heads for each nesting level

- Span-based methods: Predict all entity spans regardless of overlap

- Hypergraph-based models: Represent complex entity relationships as graph structures

Modern NER with transformers achieves 93-95% F1 scores on standard English benchmarks like CoNLL-2003, approaching human inter-annotator agreement. The main challenges remain computational cost and domain adaptation—fine-tuning large models requires significant GPU resources and carefully curated training data.

Step-by-Step: How to Build a Working Named Entity Recognition System

Theory meets practice. Let’s walk through building real NER systems using popular frameworks.

1. Preparing Your Dataset

Quality data makes or breaks NER models. Start with raw text relevant to your domain—news articles, medical records, customer support tickets, or scientific papers.

Tokenization: Break text into tokens (words and punctuation). Different tokenizers make different choices. SpaCy’s tokenizer handles contractions (“don’t” → “do”, “n’t”) and punctuation differently than BERT’s WordPiece tokenizer, which splits unknown words into subword units (“unhelpful” → “un”, “##help”, “##ful”).

Annotation Formats: The NER community standardized on several formats:

CoNLL Format: Each line contains a token and its tag, with blank lines separating sentences:

New B-LOC

York I-LOC

City I-LOC

is O

beautiful O

. OBIO Tagging Scheme:

- B (Begin): First token of an entity

- I (Inside): Subsequent tokens of the same entity

- O (Outside): Not part of any entity

BILOU Tagging: Adds more granularity:

- B (Begin), I (Inside), L (Last token of multi-token entity)

- U (Unit): Single-token entities

- O (Outside)

BILOU helps models distinguish between “Washington” (U-PER) and “George Washington” (B-PER, L-PER), improving boundary detection.

JSON/Spacy Format: Modern tools like Spacy prefer JSON with character offsets:

{

"text": "Apple Inc. is based in Cupertino.",

"entities": [

[0, 10, "ORG"],

[27, 36, "LOC"]

]

}Choose formats compatible with your chosen framework. Converting between formats is common—write scripts early to handle conversions smoothly.

2. Training a spaCy NER Model

SpaCy offers an excellent starting point for custom NER with minimal code. Here’s the conceptual workflow:

Data Preparation: Convert your annotations to SpaCy’s format. Each training example needs the text and entity spans with labels.

Model Configuration: SpaCy 3.x uses config files defining the training pipeline. For NER, you typically want:

- Tokenizer (spaCy’s default works well)

- Entity Recognizer component

- Training parameters (learning rate, batch size, iterations)

Training Process: SpaCy trains by:

- Initializing the model with random weights or pre-trained embeddings

- Feeding batches of annotated examples

- Calculating loss (difference between predictions and true labels)

- Updating weights through backpropagation

- Evaluating on held-out development data

Key Parameters to Tune:

- Dropout: Randomly disabling neurons during training prevents overfitting. Start around 0.3-0.5.

- Learning rate: Controls update step sizes. Too high causes instability; too low slows training. Try 0.001 initially.

- Batch size: Larger batches provide more stable gradients but require more memory. 8-32 works for most datasets.

- Iterations: Monitor performance on development data—stop when scores plateau or decline (early stopping).

SpaCy’s efficiency makes it ideal for rapid prototyping. You can train decent models on thousands of examples in minutes on a CPU, though GPUs accelerate training significantly.

3. Training a Transformer on Hugging Face

For state-of-the-art accuracy, Hugging Face Transformers provides easy access to BERT, RoBERTa, and hundreds of other pre-trained models.

Token Classification Pipeline: Hugging Face treats NER as token classification—predict a label for each input token.

Model Selection Tips:

Base vs Large Models: Base models (110M parameters for BERT-base) train faster and require less memory. Large models (340M+ parameters) achieve slightly higher accuracy but demand GPUs with 16GB+ memory and longer training times. For most applications, base models provide the best accuracy-efficiency trade-off.

Distilled Models: DistilBERT and similar models compress large models by 40-50% while retaining 95%+ of the accuracy. Perfect for production deployment where latency matters.

Domain-Specific Pre-Training: BioBERT for medical text, SciBERT for scientific papers, FinBERT for financial documents—these models were pre-trained on domain-specific corpora, giving them a head start on specialized vocabulary and concepts.

Multilingual Models: mBERT and XLM-RoBERTa support 100+ languages, enabling cross-lingual transfer and low-resource language NER.

Training Workflow:

- Load a pre-trained model and tokenizer

- Tokenize your training data (handle subword tokenization carefully—entity labels must align with subword tokens)

- Configure the token classification head for your entity labels

- Fine-tune using training examples

- Evaluate and iterate

Critical Consideration: Subword tokenization creates misalignment between your original word-level annotations and the model’s token-level inputs. “Washington” might become [“Wash”, “##ington”]. Your training code must handle this, typically by:

- Copying the label to the first subword token

- Marking other subword tokens with special “ignore” labels

- Reconstructing entities from subword predictions during inference

Fine-tuning BERT-base on 10,000 annotated sentences typically achieves strong performance, though more data always helps. Budget 2-5 epochs of training, monitoring development set scores to prevent overfitting.

4. Evaluation Metrics

How do you know if your NER model actually works? Precision, recall, and F1 scores provide the standard measurement framework.

Precision: Of all the entities your model predicted, what percentage are correct?

Precision = True Positives / (True Positives + False Positives)High precision means few false alarms—when the model says “this is a PERSON entity,” it’s usually right. Low precision indicates the model over-predicts, seeing entities everywhere.

Recall: Of all the true entities in the text, what percentage did your model find?

Recall = True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives)High recall means comprehensive coverage—the model finds most of the entities. Low recall indicates the model misses many entities, either predicting “O” (outside) or using wrong labels.

F1 Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, balancing both concerns:

F1 = 2 × (Precision × Recall) / (Precision + Recall)F1 provides a single number for model comparison. A model with 90% precision and 60% recall has F1 = 72%. Another with 75% precision and 75% recall also has F1 = 75%, but different error characteristics.

Explained Simply: Imagine searching for all mentions of diseases in medical records. High precision means that almost everything you flag really is a disease (few false positives like “cancer fundraiser” mistaken for a disease mention). High recall means you find nearly every disease mention (few missed entities). F1 balances these—you want comprehensive coverage without drowning in false positives.

Common NER Evaluation Mistakes:

Exact Match Requirement: Standard evaluation requires perfect boundary matching. Predicting “New York” when the true entity is “New York City” counts as both a false positive and a false negative. This strictness penalizes near-misses that might be acceptable in applications.

Label Mismatch: Correctly identifying entity boundaries but wrong type (“Paris” labeled LOC vs GPE—geopolitical entity) counts as wrong.

Entity-Level vs Token-Level: Most papers report entity-level F1, but some report token-level metrics. Token-level scores appear higher because they evaluate each token independently. Always check which metric is being reported for fair comparisons.

Partial Credit and Span-Level Scoring: Recognizing these issues, researchers developed alternative metrics:

Relaxed Matching: Accept partial overlaps or boundary errors if the main entity is captured.

Mention Detection: Evaluate entity boundary detection separately from type classification.

SemEval-style Metrics: Partial credit for partial overlaps, scored on a sliding scale.

Choose evaluation metrics matching your application needs. For a redaction system protecting privacy, you might prioritize recall (catch all names) over precision (some false positives are acceptable). For information extraction feeding structured databases, precision matters more—wrong entities corrupt downstream analytics.

Always evaluate on held-out test data the model has never seen during training. Randomly split your annotated data into training (70-80%), development (10-15%), and test (10-15%) sets before starting model development.

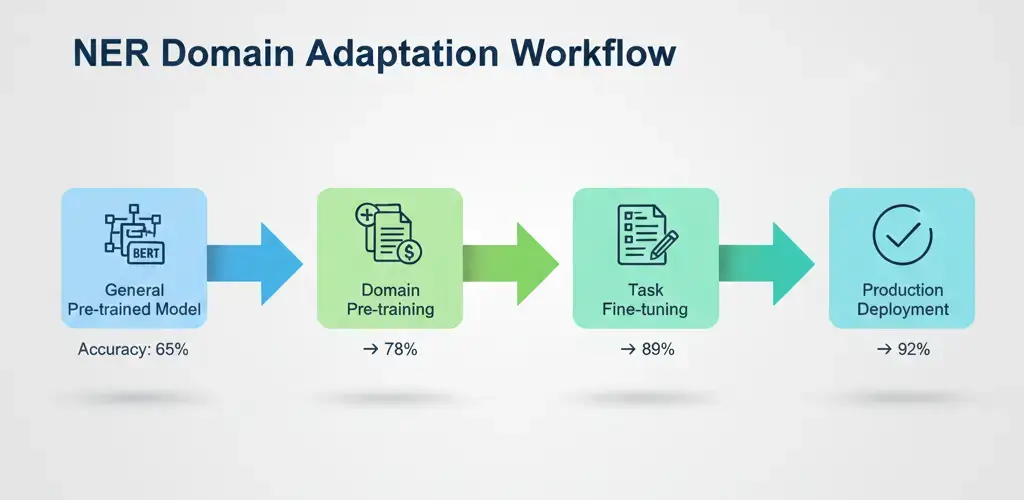

Domain Adaptation: Making Named Entity Recognition Work in the Real World

General-purpose NER models trained on news articles fail spectacularly when applied to specialized domains. A model that excels at identifying politicians and cities crumbles when faced with gene names and chemical compounds. Domain adaptation bridges this gap.

Why General NER Models Fail in Specialized Domains

The vocabulary mismatch alone creates massive problems. Medical text swarms with terms like “myocardial infarction,” “ACE inhibitors,” and “left ventricular dysfunction” that appear nowhere in news training data. The model has never learned that these are entity types worth recognizing.

Entity type differences compound the challenge. General models recognize PERSON, LOCATION, and ORGANIZATION. Medical NER needs DISEASE, DRUG, SYMPTOM, PROCEDURE, and GENE. Even when surface forms overlap, meanings diverge—”culture” in news text differs from “bacterial culture” in microbiology.

Writing style and text structure vary dramatically. News articles follow journalistic conventions with clear sentence structure. Scientific papers use dense technical jargon, complex noun phrases, and abbreviated references. Social media throws grammar out the window entirely. Models trained on one style struggle with others.

Gazetteers, Vocabulary Expansion, and Feature Engineering

Gazetteers are dictionaries of known entities that supplement machine learning models. For pharmaceutical NER, load FDA drug databases, WHO international non-proprietary names, and commercial product lists. The model learns that gazetteer matches strongly indicate entity presence.

Gazetteers help most with rare and emerging entities. New drugs, recently discovered genes, or newly formed organizations won’t appear in training data. Gazetteers provide instant coverage, though they can’t handle creative mentions or contextual variations.

Vocabulary Expansion: Retrain your tokenizer or add domain-specific vocabulary to handle specialized terms. BERT’s WordPiece tokenizer might split “pembrolizumab” into meaningless fragments. Add pharmaceutical terms to the vocabulary so the model treats them as single units, improving representation quality.

Feature Engineering (for non-transformer models): Incorporate domain-specific features—patterns in medical codes, chemical formula recognition, or journal citation formats. Even transformer models benefit from auxiliary inputs like section headers in research papers or metadata fields.

Transfer Learning and Few-Shot Training

Transfer Learning: Start with a model pre-trained on large amounts of domain-relevant text, then fine-tune on your specific entity recognition task. BioBERT was pre-trained on PubMed papers; SciBERT on scientific literature; LegalBERT on court documents. These models learned domain vocabulary and writing patterns, giving your NER task a huge head start.

The impact is dramatic. Fine-tuning SciBERT on 1,000 annotated chemistry papers might achieve F1 scores that require 5,000-10,000 examples starting from general BERT. Domain-specific pre-training acts as a force multiplier for limited annotation budgets.

Few-Shot Training: Recent advances in prompt engineering and meta-learning enable learning from tiny datasets—sometimes just dozens of examples. Techniques include:

Prompt-Based Learning: Frame NER as a fill-in-the-blank task. “The patient was diagnosed with ___.” The model fills the blank and you extract entities from completions.

Prototypical Networks: Learn entity type representations from a few examples, then classify new mentions by similarity to these prototypes.

Data Augmentation: Synthesize training examples through back-translation, entity replacement, or GPT-generated similar sentences.

Few-shot approaches work best for adding new entity types to existing systems. If you’ve trained a solid medical NER model and need to add genetic variant recognition, few-shot methods might achieve decent coverage with minimal annotation effort.

Active Learning Workflows

Annotating training data is expensive—expert time costs money. Active learning maximizes label efficiency by strategically selecting the most informative examples to annotate next.

The Active Learning Loop:

- Train an initial model on a small seed dataset

- Apply the model to a large pool of unlabeled examples

- Select examples where the model is most uncertain or likely to learn

- Have human annotators label these examples

- Retrain the model including the new labels

- Repeat until performance plateaus or budget exhausts

Selection Strategies:

Uncertainty Sampling: Choose examples where the model’s predictions have low confidence—probability scores near 0.5, or high disagreement between entity type options.

Diversity Sampling: Ensure selected examples cover different topics, writing styles, and entity distributions. Avoid querying 100 similar sentences.

Expected Model Change: Select examples that would most change the model’s parameters if added to training data.

Studies show active learning can reduce annotation requirements by 50-70% compared to random sampling. For a target F1 score of 85%, active learning might achieve it with 3,000 annotated sentences instead of 10,000. In specialized domains where expert annotators charge $100+/hour, these savings compound quickly.

Combine active learning with pre-annotation—use your current model to generate draft labels, then have annotators correct them. Correcting is faster than annotating from scratch, especially when model quality improves over iterations.

Named Entity Recognition for Low-Resource Languages (Including Urdu Examples)

Most NER research focuses on English, with decent coverage for Chinese, Spanish, German, and other “high-resource” languages. But what about the thousands of languages with limited training data, inconsistent spelling, and mixed-script usage?

Challenges: Spelling Variation, Code-Mixing, and Lack of Corpora

Spelling Variation: Many languages lack standardized orthography. Urdu, written in Perso-Arabic script, exhibits significant spelling variation—”Pakistan” might appear as “پاکستان” or “پاكستان” depending on character choices. Romanized versions introduce more chaos: “Pakistan,” “Pakistaan,” “Paakistan.”

Code-Mixing: Multilingual speakers mix languages within sentences. Indian social media posts blend Hindi, English, and regional languages: “Kal main Delhi jaa raha hoon for the conference.” An NER system must recognize “Delhi” (Hindi/Urdu) and “conference” (English) within code-mixed text.

Lack of Annotated Corpora: While English has millions of annotated sentences across diverse domains, low-resource languages might have thousands at best, often from narrow domains like news. Scientific papers, social media, and conversational text lack annotations entirely.

Script and Typography: Some languages use non-Latin scripts with complex rendering rules. Arabic-script languages write right-to-left, with characters that change form based on position (initial, medial, final, isolated). Tokenization becomes language-specific rather than simple whitespace splitting.

How Multilingual Transformers Help

Cross-Lingual Transfer: mBERT and XLM-RoBERTa were trained on 100+ languages simultaneously. They learn that “Paris,” “París,” “پیرس” (Urdu), and “パリ” (Japanese) refer to the same entity through alignment in multilingual text. This enables zero-shot transfer—a model fine-tuned for NER in English recognizes entities in Urdu without any Urdu training data.

Zero-shot transfer provides a starting point but rarely achieves high accuracy. Fine-tuning with even small amounts of target language data significantly improves performance—sometimes just 100-500 annotated sentences in the target language doubles F1 scores over pure zero-shot.

Language Adapters: Modular components added to transformers that specialize in specific languages. Train a language adapter on large amounts of Urdu text, then combine it with an NER task adapter trained on English or multilingual data. Adapters enable efficient parameter sharing across languages.

Mini Case Study: Urdu/Hinglish Named Entity Recognition Dataset

Let’s walk through building an NER system for Urdu social media text with code-mixing.

The Dataset: 2,000 Urdu tweets annotated for PERSON, LOCATION, and ORGANIZATION. Text includes pure Urdu (“عمران خان نے اسلام آباد میں تقریر کی” – Imran Khan gave a speech in Islamabad), pure English, and code-mixed examples.

Challenges Observed:

- Name mentions in both Urdu script and Romanized form

- Hashtags and @-mentions as entities

- Informal language with heavy abbreviation

- Location names in English within otherwise Urdu text

Approach:

- Pre-processing: Normalize Urdu characters (convert different Unicode forms to standard). Handle hashtags specially—”#ImranKhan” should be recognized as a PERSON entity.

- Model Selection: Start with XLM-RoBERTa (multilingual, handles both Urdu and English)

- Training Strategy:

- Use 1,500 tweets for training, 250 for development, 250 for test

- Augment with English NER data through multilingual training

- Fine-tune for 5 epochs with learning rate 2e-5

- Results: Achieved 76% F1 on test set (compared to 45% F1 for English-only model without Urdu fine-tuning)

Key Learnings: Mixed-script entities posed the biggest challenge. “New York” appeared in Latin script even within Urdu sentences—the model sometimes missed these because context looked unfamiliar. Adding more code-mixed examples improved coverage.

Practical Preprocessing Steps

Script Normalization: Convert between Urdu/Arabic Unicode normalization forms. Remove or normalize diacritics (usually omitted in social media).

Romanization Handling: Decide whether to romanize all Urdu text, keep native scripts separate, or handle both. No universal best answer—experiment with your data.

Tokenization: Use multilingual tokenizers that handle right-to-left scripts. Test whether character-level features help (they often do for languages with rich morphology).

Entity Gazetteers: Build lists of Pakistani person names, cities, and organizations in both scripts. This bootstraps coverage for common entities.

Leveraging Related Languages: Hindi and Urdu share much vocabulary and grammar. Use Hindi training data to improve Urdu NER through cross-lingual transfer. Similarly, leverage Arabic resources for Urdu Arabic-script processing.

The key insight: you can build functional NER systems for low-resource languages by combining multilingual pre-trained models, small amounts of target language annotation, cross-lingual transfer, and domain-specific gazetteers. Perfect accuracy isn’t achievable with limited resources, but practical systems that catch 70-80% of entities enable useful applications.

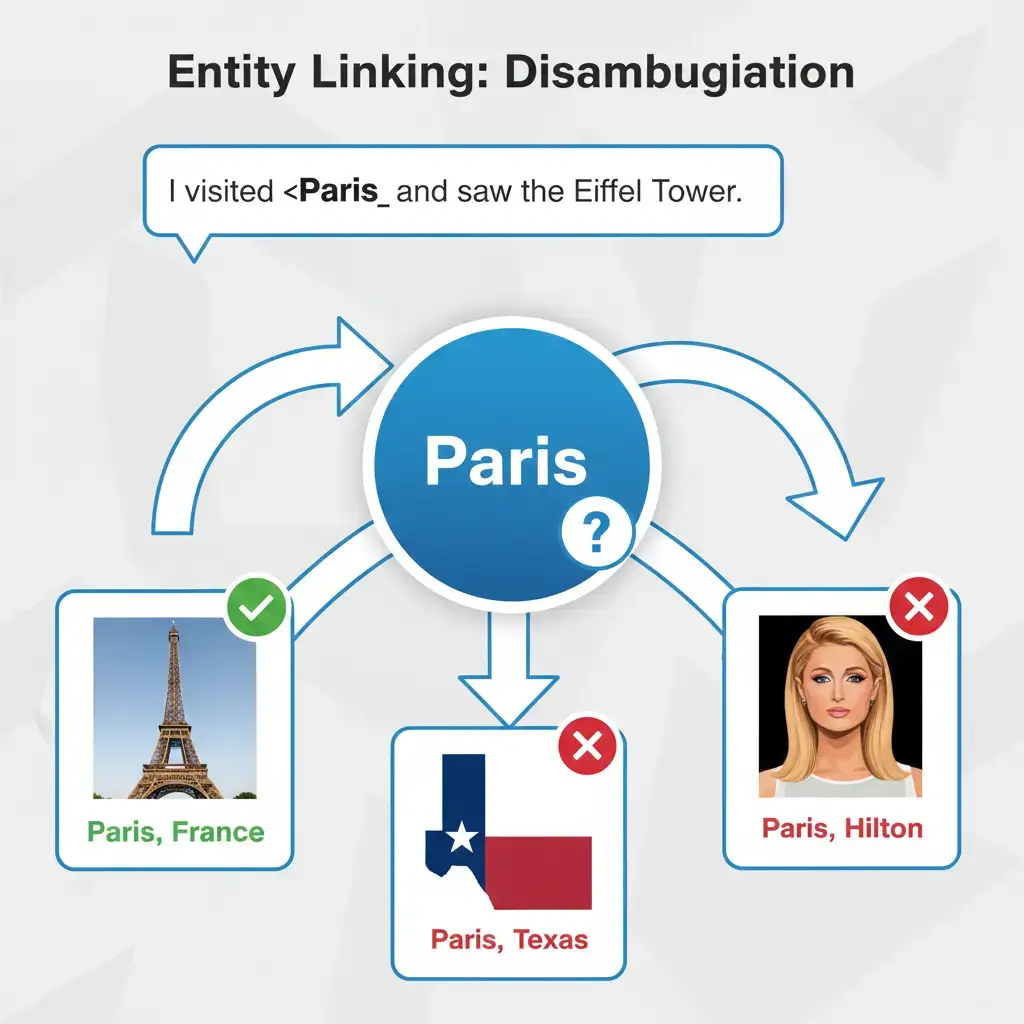

Entity Linking: Going Beyond Extraction

Named Entity Recognition identifies “Paris” in text. Entity Linking answers “Which Paris?”—the capital of France, the city in Texas, the character from Greek mythology, or Paris Hilton?

Disambiguation Challenges

Ambiguity is everywhere. “Washington” could be:

- George Washington (person)

- Washington state (location)

- Washington D.C. (location)

- University of Washington (organization)

- Washington Post (organization)

Context provides clues. “Washington crossed the Delaware” clearly refers to George Washington. “Washington passed new legislation” likely means D.C. But “Washington won the game” could be Washington Commanders, Washington Huskies, or Washington Nationals—context determines everything.

Entity linking resolves these ambiguities by connecting extracted mentions to unique identifiers in knowledge bases like Wikipedia, Wikidata, or domain-specific databases.

Disambiguation Techniques

Knowledge Base Embeddings: Represent entities and contexts as vectors in the same embedding space. When you encounter “Paris” in “Paris is the city of lights,” compute embeddings for the mention and its context, then find the knowledge base entity with the most similar embedding. Paris, France will match more closely than Paris, Texas because “city of lights” appears in contexts related to the French capital.

Prior Probability and Popularity: Some entities are simply more common. “Apple” mentions in news text refer to the company far more often than the fruit. Entity linkers use prior statistics—how frequently each entity gets mentioned overall—as a baseline probability, adjusted by context.

Graph-Based Methods: Knowledge graphs encode relationships between entities. If a sentence mentions “Eiffel Tower” and “Paris” together, and the knowledge graph shows strong connections between Eiffel Tower and Paris, France (not Paris, Texas), this reinforces the correct linking decision.

Collective Disambiguation: Rather than linking each mention independently, consider all mentions in a document together. A paragraph mentioning “Jordan,” “basketball,” and “Chicago Bulls” should link “Jordan” to Michael Jordan, not the country. Document-level context dramatically improves accuracy.

Wikidata, Wikipedia, BLINK, and Entity Embeddings

Wikipedia serves as the standard knowledge base for general-domain entity linking. Each Wikipedia page represents a distinct entity with a unique identifier. The page text, links, and categories provide rich context for matching mentions to pages.

Wikidata extends this with structured data—birth dates, occupation codes, geographic coordinates, and millions of relationships. Wikidata’s machine-readable format makes it perfect for entity linking systems that need to query entity properties programmatically.

BLINK (Bootstrapped Language-Model-Based Entity Linking) represents the current state-of-the-art. BLINK uses BERT to encode both entity mentions (with context) and entity descriptions (from Wikipedia). Entity linking becomes a nearest-neighbor search in embedding space—find the entity description most similar to the mention context.

BLINK achieves 85%+ accuracy on standard benchmarks, approaching human performance. The key innovation is jointly training the mention encoder and entity encoder so that compatible mentions and entities naturally cluster together in the embedding space.

Fine-Grained Entity Types: Recent systems predict entity types alongside linking. Not just “Paris is a LOCATION” but “Paris is a CITY, specifically a CAPITAL_CITY in EUROPE.” These fine-grained types help downstream applications—a travel app might treat cities differently than countries or regions.

NER + EL Pipelines Used in Search Engines

Google, Bing, and other search engines rely heavily on combined NER and entity linking pipelines.

When you search for “jaguar problems,” the search engine must determine whether you’re asking about car reliability or wildlife conservation. Entity linking examines your search history, location, and query patterns. Previous searches for “car maintenance” suggest the automobile; searches for “endangered species” point toward the animal.

Search results then organize by entity. Google’s Knowledge Graph panels show entity-specific information boxes—for “Marie Curie,” you see birth date, nationality, Nobel Prizes, and related people. This information comes from entity linking connecting your search to Wikidata/Wikipedia entries, then pulling structured data.

Query understanding for voice assistants relies on the same technology. When you ask “How old is Washington?”, the assistant must disambiguate which Washington, link to the correct knowledge base entity, then retrieve the relevant property (George Washington’s age at death, or Washington state’s founding date).

E-commerce platforms use NER + entity linking for product search. Searching for “Apple Watch” should return smartwatches, not fruit-themed watches. Entity linking connects “Apple” to Apple Inc., then constrains product results to that brand.

Building Your Own Training Dataset

Quality training data is the foundation of successful NER systems. Here’s how to create it properly.

Annotation Guidelines and Label Definitions

Start with Crystal-Clear Definitions: Write precise descriptions of each entity type with positive and negative examples.

For PERSON:

- Include: Individual human names, nicknames, usernames when referring to people

- Exclude: Fictional characters (mark as FICTIONAL_PERSON), deity names (mark as DEITY), animal names

- Edge cases: “Dr. Smith” includes the title; “the president” without a name is not tagged

For ORGANIZATION:

- Include: Companies, government agencies, non-profits, universities, sports teams, bands

- Exclude: Building names without organizational context (“visited the Pentagon” vs “the Pentagon announced”)

- Edge cases: Subsidiaries (“Apple’s iPhone division”—mark entire phrase or just “Apple”?)

Document Edge Cases: Real text is messy. Your guidelines must cover:

- Abbreviations: Is “U.S.” a location? What about “USA”?

- Possessives: Does “Microsoft’s” include or exclude the possessive ‘s?

- Conjunctions: In “New York and London,” do you mark each city separately or the entire phrase?

- Nested entities: “University of California, Berkeley”—one entity or nested?

Provide Abundant Examples: Show 10-20 examples for each entity type in diverse contexts. Include tricky cases that confuse annotators.

Version and Update: Annotation guidelines evolve as you discover new edge cases. Version your guidelines and retrain annotators when rules change. Track which examples were annotated under which guideline version.

Inter-Annotator Agreement (IAA)

Multiple annotators should achieve high agreement on the same text. Low IAA indicates ambiguous guidelines or insufficient annotator training.

Measuring IAA: Cohen’s Kappa or F1 score between annotators quantifies agreement. Target Kappa > 0.80 for production datasets. Lower scores (0.60-0.80) suggest revising guidelines or additional training.

Regular Calibration: Schedule weekly sessions where annotators discuss disagreements. These conversations reveal guideline ambiguities and refine shared understanding.

Adjudication Process: When annotators disagree, have an expert reviewer make final decisions. Document these decisions to update guidelines.

Crowdsourcing Tips and Quality Control

Professional annotators are expensive. Crowdsourcing platforms like Amazon Mechanical Turk offer cheaper alternatives but require careful quality management.

Task Design: Make annotation tasks simple and clear. Instead of asking workers to annotate an entire document, show one sentence at a time with highlighted potential entities and ask for confirmation/correction.

Qualification Tests: Create tests covering your entity types and edge cases. Only workers who pass qualify for your tasks.

Redundancy and Voting: Have 3-5 workers label each example. Use majority voting or probability thresholds to establish final labels.

Gold Standard Data: Mix pre-annotated examples with hidden correct answers into your task batch. Workers who frequently miss these gold standard cases get removed or given lower weight.

Feedback and Training: Provide immediate feedback on gold standard examples so workers learn your guidelines through practice.

Payment and Incentives: Fair payment improves quality. Workers rushing through tasks for pennies produce garbage data. Pay enough to make careful work worthwhile.

Sample Annotation Specification

Here’s an example specification for a financial news NER project:

Entity Types:

- COMPANY: Corporate entities (Apple Inc., Goldman Sachs)

- PERSON: Individual names (Elon Musk, Janet Yellen)

- MONEY: Monetary amounts ($50M, 100 billion euros)

- PERCENT: Percentages (25%, three-quarters)

- DATE: Temporal expressions (Q3 2024, yesterday)

Annotation Process:

- Read entire sentence for context

- Identify entity spans using longest possible match

- Select primary entity type

- Mark ambiguous cases with notes for review

Quality Checks:

- All dollar amounts must be tagged as MONEY

- Corporate suffixes (Inc., Corp., LLC) are included in COMPANY entities

- Fiscal periods (Q1, Q2) are tagged as DATE

- When in doubt, tag as entity rather than leaving untagged

Error Analysis: How to Improve an Named Entity Recognition Model

Your first model never performs perfectly. Error analysis reveals improvement paths.

Typical Model Mistakes

Boundary Errors: The model correctly identifies entity types but gets boundaries wrong. Predicting “New” instead of “New York” or “New York City” instead of “New York.”

Type Errors: Correct boundaries but wrong classification. Tagging “Washington” as LOC when the context indicates PERSON.

False Positives: Predicting entities where none exist. Seeing “Apple” in “an apple a day” as an organization.

False Negatives: Missing entities entirely—predicting O (outside) for tokens that should be entity parts.

Consistency Errors: The model tags “Microsoft” as ORG in paragraph one but misses it in paragraph three. Inconsistent predictions across similar contexts indicate the model hasn’t fully learned the pattern.

Boundary Errors vs Type Errors

Boundary errors often stem from:

- Inconsistent training annotations (sometimes including titles like “Dr.” or “CEO”, sometimes not)

- Ambiguous multi-word expressions

- Tokenization mismatches between training and inference

Solutions:

- Review and standardize training annotations

- Add more examples of problematic boundary cases

- Consider span-based models instead of token classification

- Use BILOU tagging instead of BIO for clearer boundaries

Type errors usually indicate:

- Insufficient training examples for that entity type

- Overlapping characteristics between types (is “Apple” an ORG or PRODUCT?)

- Weak context signals that help disambiguation

Solutions:

- Collect more training data for confused types

- Add gazetteer features or type-specific patterns

- Refine entity type definitions to reduce overlap

Practical Debugging: Confusion Patterns and Mis-Labeled Spans

Create a Confusion Matrix: Show which entity types get confused most often. If LOC frequently gets misclassified as ORG, investigate why. Perhaps your training data lacks clear examples distinguishing places from institutions.

Analyze False Positives: Sort false positives by confidence score. High-confidence mistakes indicate systematic errors—the model strongly believes wrong answers. These often reveal training data issues or guideline ambiguities.

Low-Confidence Predictions: Examine predictions with probability scores near 0.5. These are the model’s “guesses.” Add similar examples to training data to teach clearer decision boundaries.

Error Patterns by Entity Length: Are single-token entities more problematic than multi-token entities? This suggests BIO tagging issues or inadequate context window.

Domain-Specific Errors: Medical models might confuse symptoms and diseases. Legal models might struggle with nested citations. Domain analysis reveals specific improvements needed.

How to Fix Errors Using Data Tweaks

Targeted Data Collection: Rather than randomly adding more training data, focus on error-prone cases. If the model struggles with abbreviated company names, collect 100 examples of abbreviations and add them to training.

Synthetic Data Generation: Create training examples by systematically varying problematic patterns. If “Dr. Smith” gets split incorrectly, generate examples: “Dr. Johnson,” “Dr. Williams,” “Dr. Rodriguez” with different contexts.

Data Augmentation:

- Entity replacement: Swap entity mentions while preserving labels (“Microsoft announced” → “Google announced”)

- Back-translation: Translate sentences to another language and back, creating paraphrases

- Contextual word replacement using language models

Hard Negative Mining: Add examples that look like entities but aren’t, teaching the model to avoid false positives. For financial NER, include sentences with price-like patterns that aren’t actually monetary entities.

Annotation Refinement: Sometimes errors reveal genuine annotation mistakes in training data. Review systematically—incorrect training labels teach models wrong patterns.

Iterate: fix issues, retrain, evaluate, analyze new errors. Each cycle improves model reliability.

Deploying Named Entity Recognition in Production

Building a model is one thing. Running it at scale on production traffic is entirely different.

Latency, Batching, and Streaming Text

Latency Requirements: Real-time applications (chatbots, voice assistants) need responses in milliseconds. Batch processing (daily report generation) tolerates seconds or minutes per document. Your latency budget determines architecture choices.

Model Optimization:

- Quantization: Reduce model precision from 32-bit to 8-bit integers. Inference becomes 3-4x faster with minimal accuracy loss.

- Knowledge Distillation: Train smaller “student” models to mimic larger “teacher” models. DistilBERT runs 60% faster than BERT-base with 97% of the accuracy.

- ONNX Runtime: Convert PyTorch/TensorFlow models to ONNX format for optimized inference across hardware.

- TensorRT: NVIDIA’s inference optimizer dramatically accelerates transformer models on GPUs.

Batching Strategies: Process multiple documents together to maximize GPU utilization. Dynamic batching collects incoming requests for 50-100ms, then processes the batch together. Throughput increases 5-10x compared to one-by-one processing.

Streaming Text: For live applications processing user input character-by-character, buffer text until sentence boundaries, then run NER. Partial results update as more context arrives.

CPU vs GPU Considerations

GPUs excel at large models and high throughput. If you’re processing millions of documents daily or using BERT-large, GPUs are essential. A single V100 GPU processes ~1000 sentences/second with BERT-base.

CPUs work well for smaller models (spaCy, distilled transformers) and low-throughput scenarios. Cloud CPU instances cost 10-20x less than GPU instances. For a service processing dozens of documents per minute, CPU deployment might optimize cost-performance.

Edge Deployment: Mobile apps and IoT devices require tiny models running on CPU or specialized neural accelerators. Quantized distilled models (DistilBERT-8bit) can run on phones with acceptable latency.

Pipeline Design for High Throughput

Component Separation: Run preprocessing (tokenization, cleaning), NER inference, and post-processing (entity linking, result formatting) as separate microservices. This enables independent scaling—maybe you need 10 NER inference servers but only 2 entity linking servers.

Caching: Entity mentions repeat frequently. Cache NER results for common text patterns. News articles about Apple Inc. appear constantly—recognize the pattern once, serve cached results thereafter.

Asynchronous Processing: Queue incoming documents, process asynchronously, return results when complete. This prevents traffic spikes from overwhelming servers.

Load Balancing: Distribute requests across multiple NER servers. When one server is busy, route requests to others.

Monitoring Model Drift and Updating the Model

Data Drift: Production text distribution changes over time. News NER systems trained on 2020 data miss COVID-19 terminology. Models trained before ChatGPT don’t recognize “GPT-4” or “Claude” as entity mentions. Financial models need regular updates for newly public companies and emerging cryptocurrencies.

Performance Monitoring: Track precision, recall, and F1 on a held-out test set that gets periodically updated with recent examples. If scores drop, investigate whether new entity types, writing styles, or domains are causing issues.

Active Monitoring: Log low-confidence predictions and systematic errors. When users correct mistakes (if your UI allows feedback), use these corrections to identify problematic patterns.

Retraining Schedule: Establish regular retraining cycles—monthly or quarterly depending on domain drift speed. Include recent examples, fix discovered errors, and evaluate on fresh test data.

A/B Testing: Deploy new model versions to a subset of traffic first. Compare performance and user satisfaction metrics before full rollout.

Versioning: Maintain multiple model versions in production simultaneously. If the new model has bugs, instantly rollback to the previous version without downtime.

Production NER requires engineering effort beyond model training. Infrastructure, monitoring, and maintenance determine whether your NER system delivers lasting business value or becomes a liability.

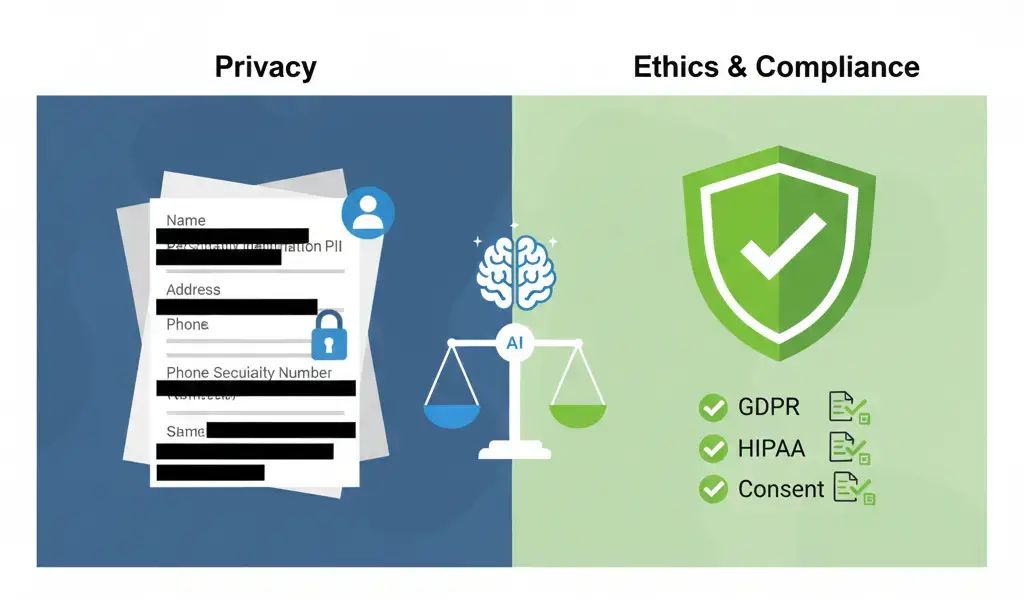

Privacy, Ethics & Responsible Use

Named Entity Recognition identifies people, places, and organizations—information that can reveal sensitive details about individuals, communities, and proprietary business activities.

Handling PII (Names, IDs, Locations)

Personally Identifiable Information extraction can violate privacy when mishandled. Names, addresses, phone numbers, email addresses, social security numbers, medical record numbers—all require careful treatment.

Legitimate Use Cases:

- Redacting PII from documents before public release

- Extracting named entities from medical records for research with proper de-identification

- Analyzing customer feedback while anonymizing user identities

Problematic Use Cases:

- Scraping social media for personal details without consent

- Building surveillance systems tracking individuals across data sources

- Identifying whistleblowers or vulnerable populations through entity extraction

The same NER technology serves both privacy-protective and privacy-invasive purposes. Context and consent matter enormously.

Redaction Pipelines

Full Redaction: Replace identified entities with generic placeholders. “Dr. Sarah Johnson treated the patient” becomes “Dr. [NAME] treated the patient.”

Pseudonymization: Replace real names with consistent fake names. “Sarah Johnson” becomes “Patient-A” consistently throughout a document set. This preserves analytical relationships (connecting multiple mentions of the same person) while protecting identity.

Selective Redaction: Remove some entity types but not others. Medical research might keep disease and treatment mentions while removing patient names and locations.

Confidence Thresholds: Set high thresholds for redaction systems—better to redact a few non-sensitive words than miss actual PII. False negatives in redaction create privacy violations; false positives merely inconvenience readers.

Human Review: Critical applications require human verification after automated redaction. Models miss entities; humans catch errors.

Data Consent and Regulations (GDPR, HIPAA)

GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) in Europe requires explicit consent before processing personal data. NER systems extracting names, locations, or other identifiers from EU residents’ data must have legal basis—usually consent or legitimate interest carefully documented.

Right to Erasure: Individuals can demand deletion of their personal data. Systems that extract and store entity mentions must support deletion upon request.

HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) in the US regulates medical information. NER systems processing protected health information require strict safeguards—encryption, access controls, audit logs, and de-identification meeting regulatory standards.

Data Minimization: Extract only the entities you actually need. If your application requires disease names but not patient names, configure your NER pipeline to only extract medical entities.

Transparency: Inform users when their data undergoes entity extraction. Privacy policies should explain what information gets extracted and why.

Ethical Concerns in Automated Extraction

Surveillance and Tracking: NER enables tracking individuals across time and data sources. While valuable for fraud detection and security, it also enables mass surveillance violating civil liberties.

Discriminatory Outcomes: Entity extraction quality varies across demographics. Models trained primarily on Western names perform poorly on names from other cultures. This creates disparate impact—critical systems might miss or misidentify non-Western names more frequently.

Context Stripping: Extracted entities lose surrounding context. “John Smith was accused of fraud” becomes “John Smith – fraud” in an entity database, potentially misrepresenting actual meaning.

Secondary Use: Entities extracted for one purpose often get repurposed. Medical research data might end up in marketing databases. Always consider potential misuse pathways.

Power Imbalances: Individuals can’t easily verify how their names and information get extracted and used across systems. Organizations hold asymmetric information power.

Responsible Development:

- Design systems with privacy and fairness from the start

- Test performance across diverse demographics

- Implement human oversight for high-stakes applications

- Provide transparency and accountability mechanisms

- Consider whether entity extraction is necessary for your use case

Technology is neutral; applications determine ethics. Build NER systems that respect human dignity, privacy, and autonomy.

Future of Named Entity Recognition: What’s Changing Next?

Named Entity Recognition is evolving rapidly. Here’s where the field is heading.

Zero-Shot & Few-Shot NER with LLMs

Large language models like GPT-4 and Claude perform entity extraction without any task-specific fine-tuning. Simply prompt: “Identify all person names in the following text:” followed by the text. The model lists entities based purely on pre-training knowledge.

Zero-Shot Performance: Current LLMs achieve 70-80% F1 on general NER tasks without any examples—impressive but below specialized models. The gap narrows as models scale.

Few-Shot Prompting: Provide 5-10 examples of entity extraction in your prompt, then ask the model to extract entities from new text. Performance jumps dramatically—sometimes matching models fine-tuned on thousands of examples.

In-Context Learning: LLMs learn from examples within the same conversation. Show examples of domain-specific entities (chemical compounds, legal citations), then extract from new documents. No training required.

Advantages: Extreme flexibility, no annotation costs, immediate deployment for new entity types or domains.

Limitations: Higher computational cost per document, less reliable than fine-tuned models, difficulty with highly specialized domains, privacy concerns sending sensitive text to external APIs.

Prompt-Based Extraction

Instead of training specialized token classification heads, frame NER as a text generation task. “Extract all company names from: [text]. Companies:” The model completes with a list.

Structured Prompting: Provide output format specifications. “Return results as JSON with keys ‘entities’, ‘type’, and ‘confidence’.”

Chain-of-Thought: Ask the model to explain its reasoning before extracting entities. “First, identify potential entities. Second, classify their types. Third, list final results.” This improves accuracy by breaking complex tasks into steps.

Iterative Refinement: Extract entities, then prompt the model to verify and correct mistakes. “Review the entity list. Are there any errors or missing entities?”

Prompt engineering becomes a core skill, replacing traditional feature engineering and model architecture design.

Multimodal NER (Images + Text)

Text isn’t the only source of entity information. Images, videos, and audio contain entities too—logos, faces, landmarks, spoken names.

Visual NER: Identify company logos in images, brand names in product photos, or landmarks in travel pictures. Models process both image pixels and any visible text, linking visual and textual entity mentions.

Document Understanding: Modern documents mix text, tables, and images. Multimodal NER extracts entities from scanned forms, invoices, contracts, and scientific papers where critical information appears in figures and captions.

Video Analysis: Extract entities from video subtitles synchronized with visual content. When a news anchor mentions “the White House” while showing building footage, the system combines text and visual recognition for higher confidence.

Cross-Modal Disambiguation: Resolve ambiguities using multiple modalities. If text says “Washington” while showing cherry blossoms and monuments, visual context disambiguates toward Washington D.C. over Washington state.

Models like CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training) enable joint text-image understanding, opening new NER possibilities.

Real-Time Extraction in Voice Assistants

Voice interfaces process spoken language continuously. Real-time NER extracts entities from audio transcripts as words are spoken.

Challenges:

- Transcription errors introduce noise (“Mary” becomes “merry”)

- No capitalization or punctuation to signal entity boundaries

- Disfluencies and self-corrections (“I need to call, uh, actually email Sarah Johnson”)

- Partial information requiring incremental updates

Streaming NER: Models process incoming words incrementally, updating entity predictions as more context arrives. “Schedule a meeting with…” (no entities yet) “…John…” (possibly PERSON) “…Smith…” (confirms PERSON: John Smith) “…at Apple…” (adds ORGANIZATION: Apple).

Pronunciation Disambiguation: Homophones create confusion. “I’ll meet at the cite” vs “I’ll meet at the site”—only context reveals whether “cite/site” is a location entity.

Speaker Identification: Entity extraction combined with speaker diarization (who’s talking) enables applications like “Schedule lunch with the person I spoke with yesterday”—linking entity references across conversations.

Voice-based NER enables hands-free information extraction for driving directions, meeting notes, shopping lists, and accessibility applications.

Where the Field Is Heading

Unified Models: Single models handling NER across languages, domains, and modalities simultaneously. Rather than training separate models for each task, massive unified models learn general entity understanding applicable everywhere.

Continual Learning: Models that update continuously from new data without catastrophic forgetting—they learn new entity types and domains while retaining previous knowledge.

Personalized NER: Systems that adapt to individual users’ entity vocabularies, nicknames, and contextual preferences. Your voice assistant learns that “Mom” refers to Jane Smith, while mine refers to Susan Johnson.

Causal Understanding: Current models correlate patterns but don’t understand causal relationships. Future NER might reason about why entities appear together, not just that they do.

Explainable Predictions: Transparency about why models made specific entity predictions. Instead of black-box outputs, systems explain “tagged as PERSON because following formal title, capitalized, and appears in subject position.”

The line between NER and general language understanding blurs as models become more capable. Eventually, entity recognition might just be one emergent capability of models that fully understand text, rather than a specialized task requiring dedicated architectures.