In 2025, invasive species in the U.S. are among the biggest threats to both nature and the economy. These unwanted species don’t just hurt native plants and animals. They destroy crops, block water systems. They fuel wildfires. Moreover, they also cost taxpayers billions each year. As the climate warms, many of them are spreading faster than ever. Thankfully, new policies and smart technologies are giving us hope. Real change will take everyone’s effort to protect our natural spaces.

This guide will help you understand everything about invasive species in the U.S. You’ll see which ones pose the greatest dangers today. You will learn how they disrupt entire ecosystems. You’ll also understand how their damage leads to massive economic losses. Most importantly, you’ll learn simple yet powerful ways to take action. Whether you’re a student, teacher, homeowner, or nature lover, you can make a difference. You have the power to stop these invaders.

What is an Invasive Species?

Not every plant or animal from another country causes problems. Your backyard tomatoes originally came from South America, and honeybees arrived from Europe. These are non-native species that peacefully coexist with local wildlife. So what makes an invasive species different?

An invasive species is a non-native organism that causes harm to the environment, economy, or human health. The key word here is “harm.” While all invasive species are non-native, not all non-native species become invasive. Think of it like this: some dinner guests blend in nicely. Others eat all the food, break the furniture, and won’t leave.

Why do invasive species succeed where native species struggle? Four main factors give them an unfair advantage:

Lack of Natural Predators: Back home, these species face enemies that keep their numbers in check. In their new environment, those predators don’t exist. It’s like playing a video game with all the bosses removed.

Rapid Reproduction: Many invasive species reproduce incredibly fast. A single Asian carp can lay over a million eggs per year. Native species simply can’t compete with these population explosions.

Disturbance-Friendly Traits: Invasive species often thrive in damaged or disturbed habitats. After a flood, fire, or human development, they’re the first to move in and take over.

Climate Change Assistance: Warmer temperatures help cold-sensitive invaders spread northward. Milder winters mean fewer die-offs. Changing rainfall patterns create new suitable habitats. Climate change acts like a highway system for invasive species, helping them reach places they never could before.

Understanding these mechanisms helps us to predict which species might become problems next and how to stop them before they spread.

Top Threats in the U.S. (2025 Hot list)

In 2025, several invasive species are rapidly spreading across the U.S., causing serious harm to ecosystems and showing signs of getting even worse. The table below provides a quick overview of 10 major invaders. They were chosen to use the latest data from the USDA and state invasive species councils. It shows what type they are, where they’ve spread, and how they’re impacting the environment.

| Species Name | Type | Primary Region/States | Key Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zebra Mussels | Mollusk | Great Lakes, Mississippi River Basin | Clog water infrastructure, alter aquatic food webs |

| Feral Swine | Mammal | 35+ states (especially TX, FL, CA) | Agricultural damage, disease transmission, habitat destruction |

| Asian Carp | Fish | Mississippi River, spreading to Great Lakes | Outcompete native fish, threaten commercial fisheries |

| Emerald Ash Borer | Insect | 35+ states, eastern U.S. | Killed hundreds of millions of ash trees |

| Spotted Lanternfly | Insect | PA, NJ, MD, DE, expanding rapidly | Damages crops, fruit trees, ornamental plants |

| Cheatgrass | Plant | Western U.S., Great Basin | Increases wildfire frequency, destroys sagebrush habitat |

| Burmese Python | Reptile | Florida Everglades | Devastates mammal populations, disrupts food chains |

| Kudzu | Plant | Southeast U.S. | Smothers native vegetation, damages trees and structures |

| Lionfish | Fish | Atlantic coast, Gulf of Mexico | Preys on reef fish, threatens coral reef ecosystems |

| Brown Marmorated Stink Bug | Insect | 46+ states | Agricultural pest, nuisance in homes |

As shown in the table above, invasive species affect every region of the United States, from coastal ecosystems to mountain forests.

Regional Breakdown:

The Southeast is struggling with fast-spreading invaders like kudzu and dangerous aquatic species such as Burmese pythons. In the Great Lakes, zebra mussels and Asian carp are disrupting the region’s vast freshwater ecosystems. Out West, cheatgrass is changing natural fire patterns across millions of acres. Meanwhile, the Northeast faces a growing problem from insects like the spotted lanternfly and emerald ash borer. These insects are spreading quickly. They are damaging forests.

No part of the country is safe, these invasive species are actively expanding their reach every year.

If you want to explore how ecosystems work, The Ecology Book: Big Ideas Simply Explained is a great read. It also shows how different species affect one another. It uses visuals and clear examples to show how life on Earth stays connected.

How Invasive Species in the U.S. Are Transforming Entire Ecosystems

Let’s get specific. How exactly do these invaders wreak havoc? Understanding the step-by-step process reveals why controlling invasive species matters so much. We’ll walk through four detailed examples that show the cascade of changes one species can trigger.

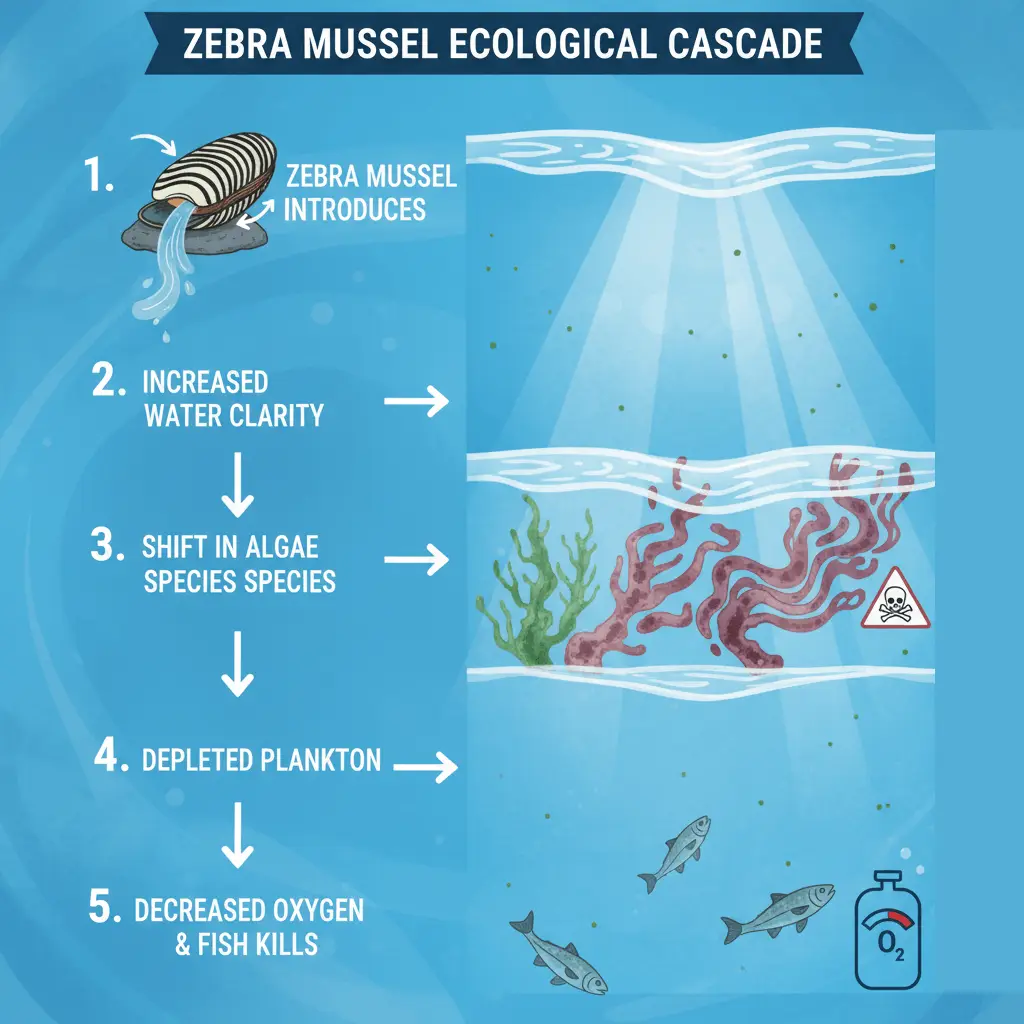

1. Zebra Mussels and the Great Lakes Food Web

Zebra mussels arrived in the Great Lakes around 1988, probably in ballast water from European ships. These tiny striped mollusks seemed harmless at first. Then they started multiplying.

Here’s the ecological domino effect:

Step 1: Zebra mussels are filter feeders. Each one filters about a liter of water per day, removing tiny plants called phytoplankton.

Step 2: With billions of mussels filtering constantly, water clarity increases dramatically. Sounds good, right? Not quite.

Step 3: Clearer water allows sunlight to penetrate deeper, changing which types of algae can grow. Some algae species produce toxins that weren’t previously a problem.

Step 4: The mussels filter out so much phytoplankton that native fish and their young lose their primary food source.

Step 5: Oxygen levels fluctuate wildly because of shifts in algae populations. Some areas experience fish kills during low-oxygen events.

When phytoplankton disappear from the food web, the whole ecosystem starts to shift in surprising ways. A tiny change at the microscopic level can ripple upward. It affects fish, birds, and even the quality of water people depend on.

2. Burmese Pythons in the Everglades

Burmese pythons established themselves in Florida’s Everglades after escaping or being released from the pet trade. These massive snakes can grow over 20 feet long and have no natural predators in Florida.

The ecological cascade unfolds like this:

Step 1: Pythons are efficient predators. They eat mammals, lots of them. Raccoons, rabbits, opossums, and even deer.

Step 2: Scientific surveys show that sightings of medium-sized mammals in python-occupied areas have declined by over 90% since 2000. Some species have essentially disappeared from large areas.

Step 3: With fewer mammals eating seeds and spreading them through their droppings, plant reproduction patterns change. Some plants can’t disperse their seeds as effectively.

Step 4: Fewer mammals mean there is less browsing pressure on certain plants. This allows some vegetation to grow unchecked. Meanwhile, other plants struggle.

Step 5: The loss of small mammals affects other predators too. Native species like bobcats and panthers face increased food competition.

Top predators play a major role in shaping whole ecosystems. When an invasive predator wipes out important prey species, it triggers a chain reaction. This affects plant growth. It also impacts seed spreading. It even threatens the survival of other predators. The Everglades ecosystem never evolved with large constrictor snakes, so it’s struggling to keep up with this sudden new threat.

3. Cheatgrass and Western Wildfire Cycles

Cheatgrass is an annual grass from Eurasia that now dominates over 100 million acres across the American West. It seems like just another plant, but it has completely transformed the fire ecology of the Great Basin.

Here’s how cheatgrass rewrites the rules:

Step 1: Cheatgrass grows quickly in spring, then dies and dries out by early summer, creating highly flammable fuel across vast areas.

Step 2: This dried grass increases fire frequency dramatically. Areas that once burned every 60-110 years now burn every 3-5 years.

Step 3: Native sagebrush ecosystems evolved with infrequent fires. Sagebrush takes decades to mature and can’t survive frequent burning.

Step 4: After each fire, cheatgrass seeds sprout quickly, but sagebrush doesn’t recover. The habitat converts from diverse sagebrush shrubland to cheatgrass monoculture.

Step 5: Sage grouse, pygmy rabbits, and hundreds of other species that depend on sagebrush lose their habitat. Biodiversity plummets.

Invasive species can completely change how natural disturbances work. For example, cheatgrass increases how often fires occur. This makes it harder for native plants to survive. It changes the whole environment so they can’t live there anymore. This process, called habitat conversion, is one of the biggest threats to biodiversity.

Economic and Ecosystem Service Costs of Invasive Species in the U.S.

The price tag for invasive species in the U.S. is staggering. But these aren’t just abstract numbers. They represent real costs to taxpayers, businesses, and communities across America.

| Cost Category | Estimated Annual Cost | Cost Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | $40 billion | Crop damage from insects (Spotted Lanternfly, crop pests), livestock disease (Feral Swine), and weed control. |

| Water Infrastructure | $25 billion | Cost of clearing Zebra Mussels from pipes, pumps, and cooling systems of power plants and municipal water facilities. |

| Recreation & Tourism | $20 billion | Loss of timber and ecosystem value due to tree-killing pests like Emerald Ash Borer and Romani Moth. |

| Forestry | $15 billion | Reduced fishing revenue due to Asian Carp or contaminated waterways; costs of maintaining parks and preserves. |

| Ecosystem Services | $20 billion | Monetary valuation of lost services includes flood control. This is due to damaged wetlands. It also covers clean water purification. Additionally, there is reduced carbon sequestration from lost forests. |

Ecologists calculate these costs by examining direct damages, such as crop losses. They also consider indirect effects like the decline in vital ecosystem services, including pollination. To put it into perspective, $120 billion equals about the yearly budget of a small country. It is roughly $360 for every U.S. household. These figures clearly show how urgent it is to take action.

Emerging & Innovative Solutions to Combat Invasive Species in the U.S.

The fight against invasive species is far from lost. Scientists, land managers, and communities are now using creative and modern strategies that move beyond old control methods. Let’s look at what’s working today and what could shape a better future.

| Method | Description & Status | Promise for Future |

|---|---|---|

| eDNA Monitoring | Environmental DNA sampling involves collecting water or soil to detect trace DNA left by an organism. | eDNA monitoring allows for the detection of species. Species like Asian Carp can be detected when populations are still too small to see. This provides a critical early warning. |

| Robotic / AI Detection | Autonomous boats or drones use AI image recognition. They identify and track invasive aquatic plants or insects (like the Spotted Lanternfly) in real-time. | Dramatically reduces manual labor and improves the scalability of detection and removal efforts, especially in hard-to-reach areas. |

| Bio-Control Programs | Introducing a specific, carefully screened natural enemy (e.g., a host-specific wasp or fungus) from the invasive species’ native range. | Bio-control offers a long-term, self-sustaining solution to keeping populations down, particularly for widely spread weeds or insects. |

| Market-Based Removal | Programs like the “Eat the Invasive” movement encourage the harvest of edible invasives. Species such as Asian Carp and certain weeds are targeted. This reduces populations while creating economic opportunity. | Provides a powerful incentive for consistent, large-scale removal that can become self-funding and change consumer perception. |

| Policy & Management Shifts | Focus on preventative measures, early detection rapid response (EDRR), and utilizing policy & management to regulate high-risk pathways (e.g., stricter ballast water rules). | Shifting from costly reaction to smarter prevention is the most effective long-term strategy for protecting native species. |

For a detailed breakdown of molecular detection methods, refer to the book Molecular Diagnostics: Fundamentals, Methods, and Clinical Applications. It provides clear explanations and offers research examples.

What You (as a Citizen / Educator / Homeowner) Can Do

Protecting our natural spaces requires a team effort. You are a crucial line of defense against invasive species U.S. threats.

1: Homeowner / Gardeners / Yard Owners

- Plant Native Species: Use native species in your gardens and landscaping. They support local insect and bird populations and require less water, fertilizer, and pest control. Rationale: Native plants offer resistance to invasives and support local ecosystem services.

- Inspect Before You Buy: Ensure all nursery plants, especially aquatic ones, are not listed as invasive in your state.

- Don’t “Hitchhike” Pests: Never move firewood long distances. The Emerald Ash Borer and other pests often travel hidden in wood, causing massive localized outbreaks.

2: Boaters / Anglers / Recreation Users

- Clean, Drain, Dry: Before moving a boat, kayak, or fishing gear from one water body to another, follow this mandatory protocol:

- Clean: Remove all visible mud, plants, fish, or animals.

- Drain: Drain all water from the motor, bilge, livewell, and bait buckets.

- Dry: Allow equipment to dry completely (ideally for $5$ days). Rationale: This prevents the microscopic transport of organisms like Zebra Mussels and aquatic plants.

- Never Dump Bait: Dispose of unused bait (fish, worms, etc.) in the trash, not into the water.

- Practice Citizen Science: Carry the reporting app. Take photos of any unusual species in a new location.

3: Educators / Students

- Incorporate Citizen Monitoring: Use local parks or school grounds to map and monitor invasive species as a class project. This is a practical form of citizen science. Rationale: Education creates awareness and provides crucial local-level data for researchers and land managers.

- Research Local Impacts: Choose a local invasive species for an in-depth project to understand its specific mechanism of habitat degradation.

Tools, Apps, and Reporting Resources for Tracking Invasive Species in the U.S.

Your camera and phone are the most powerful citizen science tools we have for early detection. The faster an invasive is reported, the higher the chance of successful, low-cost removal.

| Resource | Type | Use Guide |

|---|---|---|

| EDDMapS | App / Web Portal | Used by professionals and citizens; the gold standard for mapping species distribution. Take photos, record the GPS location, and submit. |

| iNaturalist | App / Web Portal | Excellent for general citizen science. Your sightings can be reviewed and confirmed by experts, often leading to official EDDMapS reports. |

| USDA APHIS Plant Pest Hotline | Phone / Web Form | Use this to report high-risk agricultural pests (like the Spotted Lanternfly) that require immediate regulatory action. |

| State Invasive Species Councils | Website / Local Contact | Every state has a council; search for your state’s name + “invasive species” for local identification sheets and reporting hotlines. |

How to Use Your Reporting Tool: Always capture a clear, close-up photo of the organism and any damage it’s causing. Record the exact location, GPS coordinates work best. Don’t collect or move the species unless an official specifically asks you to.

Conclusion

Invasive species in the U.S. are a real and growing threat, one that’s complex, costly, and deeply damaging. They harm our infrastructure, drain our economy, and cause major biodiversity loss. Species like the Burmese Python and Feral Swine are already disturbing natural ecosystems. These invasions put our vital environmental balance at risk.

But here’s the good news: science shows that prevention works best, especially when powered by citizen action and smart technology.

You can help protect America’s landscapes. Use the tools we’ve shared. Follow the official reporting guidelines to report invasive species. Take simple steps like cleaning your gear and planting native species.

Together, we can defend our ecosystems and keep the beauty and balance of America’s wild places alive for generations to come.

FAQs about Invasive Species in the U.S.

Zebra mussels primarily spread through human assistance. Adults can attach to boat hulls, fishing gear, and trailers, surviving out of water for several days. Their microscopic larvae (veligers) can be transported long distances in the ballast water, livewells, and bait buckets of boats that haven’t been properly cleaned, drained, and dried.

Yes, several invasive species are safe and even encouraged to eat as a control measure. The best-known example is the Asian Carp, which is a popular food fish marketed as “copi.” Other examples include certain invasive plants and even Feral Swine. Always ensure you are 100% certain of the identification, that the animal or plant is harvested legally, and that it comes from a clean water/soil source.

The spread of the Spotted Lanternfly is rapid, mainly due to human transport. While they can fly short distances, their eggs are laid on virtually any smooth surface (cars, trains, pallets, outdoor furniture). This enables rapid expansion, often covering hundreds of miles in a single year as they “hitchhike” along major transport routes, illustrating the need for proactive inspection and quarantine protocols.

Absolutely. Climate change is acting as a major catalyst for invasive species. Warmer temperatures expand the range of tropical and sub-tropical invasives, allowing them to survive further north (like the Burmese Python). Furthermore, climate change increases ecosystem disturbances (floods, droughts, wildfires), which creates new, unstable habitats where fast-growing invasive species can easily outcompete vulnerable native species.

Recommended Resources for Curious Minds

- Invasive Species: What Everyone Needs to Know by Daniel Simberloff

- A Field Guide to Invasive Plants of the United States by Sylvan Ramsey Kaufman

- Bringing Nature Home by Douglas W. Tallamy

- Where Do Camels Belong? by Ken Thompson

Further Reading / References

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS): Invasive Species

- U.S. Geological Survey (USGS): Nonindigenous Aquatic Species

- USDA National Invasive Species Information Center

- Bureau of Land Management (BLM): Cheatgrass Management

- Penn State Extension: Spotted Lanternfly

- Invasive Species Compendium

- Pimentel, D., et al. (2005). “Update on the environmental and economic costs associated with alien-invasive species in the United States.” Ecological Economics, 52(3), 273-288.

- Simberloff, D., et al. (2013). “Impacts of biological invasions: what’s what and the way forward.” Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 28(1), 58-66.

- Lockwood, J.L., Hoopes, M.F., & Marchetti, M.P. (2013). Invasion Ecology (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.