Have you ever wondered how a volcanic eruption in Iceland can change rainfall in Asia? Or how tiny ocean creatures affect the air we breathe? Welcome to earth system science, a fascinating field that shows how our planet works as one connected system.

Earth system science studies Earth as a dynamic, interconnected whole. It looks at how physical, chemical, and biological components interact. Unlike traditional Earth sciences, which study weather, rocks, or ecosystems separately, this field focuses on the big picture. It examines how the atmosphere, oceans, land, ice, and living organisms exchange matter and energy continuously.

Why does this matter? In today’s rapidly changing world, understanding these links is crucial. Climate change, deforestation, ocean acidification, and resource depletion aren’t isolated issues, they are signs of disruptions in Earth’s systems. By studying these connections, scientists can predict environmental changes, guide policies, and find ways to live more sustainably.

Earth system science emerged in the late 20th century when researchers realized studying parts of Earth in isolation wasn’t enough. In the 1980s and 1990s, satellites and computer models let scientists see the planet as a whole. The iconic “Blue Marble” photo captured this new view. Earth isn’t just dirt, water, and air side by side, it’s an integrated system where everything affects everything else.

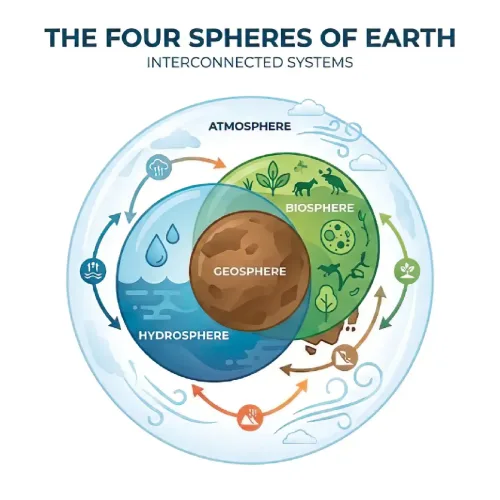

The Four Major Earth Spheres

Earth’s complex system can be divided into four major spheres, each with distinct characteristics yet constantly interacting. Understanding these spheres is fundamental to describing earth system interactions.

1. Atmosphere

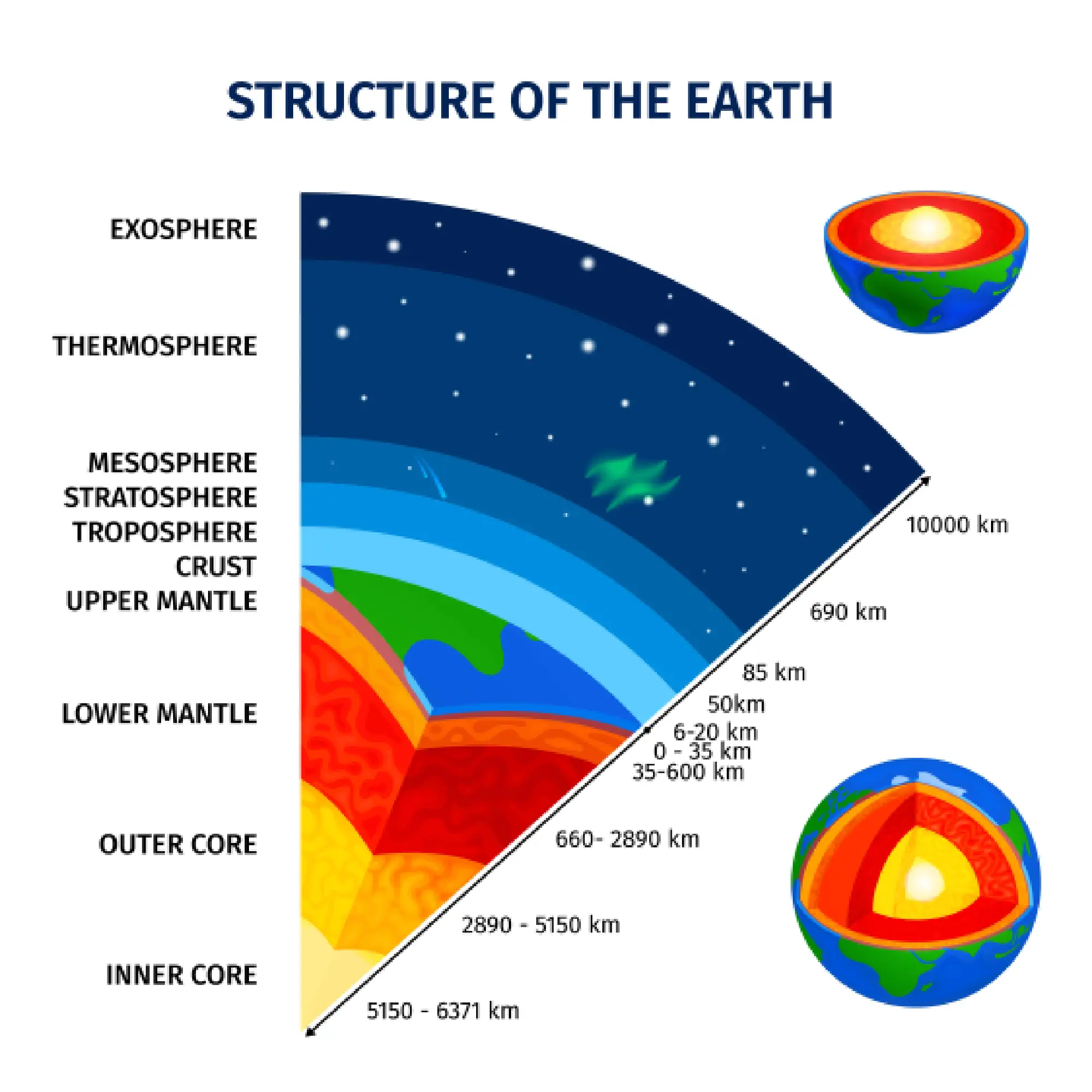

The atmosphere is the thin blanket of gases that surrounds Earth and stretches hundreds of kilometers above the surface. It is made mostly of nitrogen (78%) and oxygen (21%). Alongside these are small amounts of argon, carbon dioxide, water vapor, and other gases. Even though these trace gases exist in tiny quantities, they have a powerful influence on Earth’s climate.

The atmosphere plays several vital roles. First, it helps control Earth’s temperature through the greenhouse effect, keeping the planet warm enough for life. Next, the ozone layer shields us from harmful solar radiation. At the same time, the atmosphere drives weather and climate systems that move heat and moisture around the globe. Winds carry warm air from the equator toward the poles, helping balance temperatures worldwide.

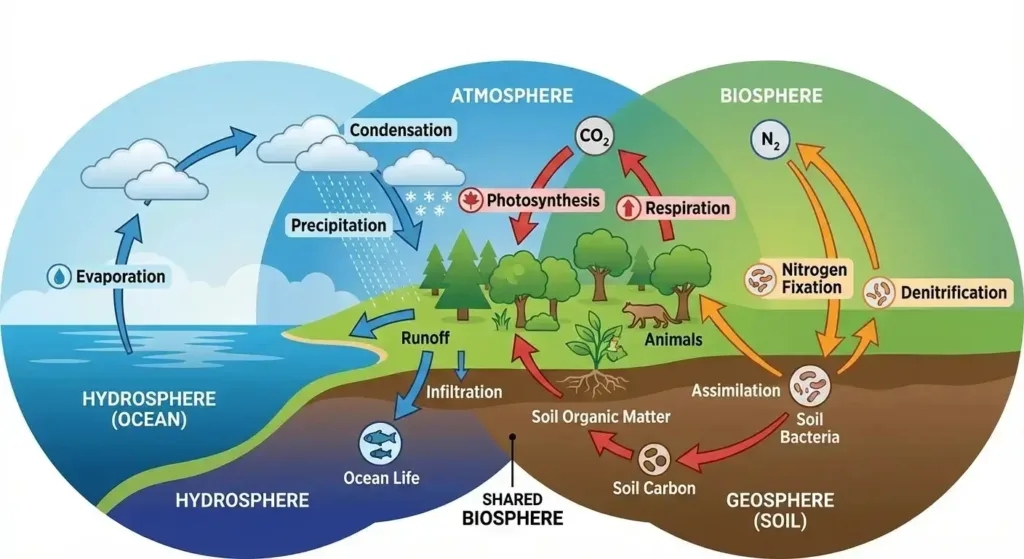

However, the atmosphere does not operate in isolation. It is always interacting with other Earth systems. Through photosynthesis and respiration, it exchanges gases with living organisms in the biosphere. Through evaporation, it gains water from oceans, lakes, and rivers, and through precipitation, it returns that water to the surface. Meanwhile, volcanic eruptions from the geosphere release gases and particles into the air, sometimes causing short-term cooling.

Together, these connections reveal how feedback mechanisms work. A change in one Earth system can trigger responses in others. In some cases, these responses strengthen the original change. In others, they weaken it. This constant interaction helps shape Earth’s climate and keeps the planet in dynamic balance.

2. Hydrosphere

The hydrosphere includes all the water on Earth. This means oceans, rivers, lakes, groundwater, ice caps, and even water vapor in the air. Oceans dominate this system. They cover about 71% of Earth’s surface and hold nearly 97% of all water. Still, here’s the twist: only 3% of Earth’s water is fresh. And most of that freshwater is trapped in ice sheets and glaciers, not easily accessible.

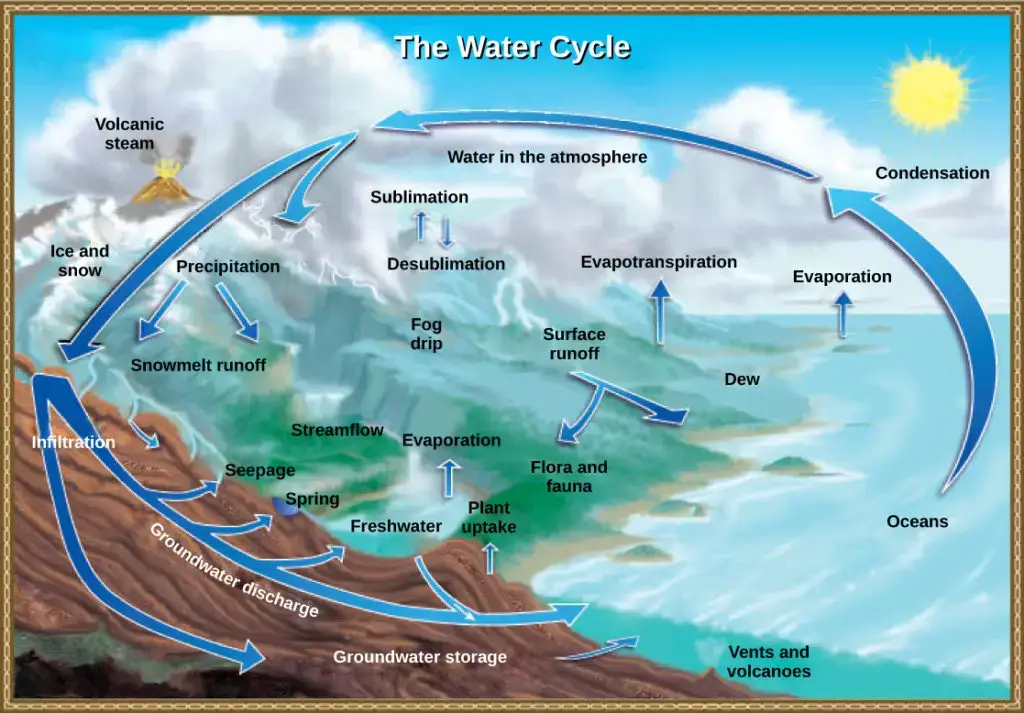

Water acts as Earth’s ultimate connector. Through the hydrological cycle, it constantly moves between different spheres. First, water evaporates. Then it condenses into clouds. After that, it falls as precipitation and flows back as runoff. But this cycle does more than shift water around. It also moves huge amounts of energy. For example, when water evaporates from the ocean, it absorbs heat. Later, when that water condenses and falls as rain, the stored energy is released. As a result, storms form and weather patterns take shape.

Oceans play a massive role in Earth system interactions. They absorb nearly 30% of carbon dioxide released by human activities. This helps slow the rise of CO₂ in the atmosphere. However, it also leads to ocean acidification. At the same time, ocean currents matter a lot. Currents like the Gulf Stream carry warm water from the tropics toward higher latitudes. Because of this movement, regional climates change dramatically. Meanwhile, the ocean surfaces constantly exchanges heat and moisture with the atmosphere. This interaction fuels powerful events such as hurricanes and monsoons.

Rivers and groundwater link the hydrosphere with both the geosphere and the biosphere. As they flow, rivers shape the land by erosion. They also carry nutrients and sediments across landscapes. More importantly, they supply freshwater that supports life on land and in water. Wetlands sit at the boundary where water meets land. These areas are incredibly productive. They support rich ecosystems and store large amounts of carbon, making them vital for environmental balance.

3. Geosphere

The geosphere includes all of Earth’s solid parts. This means the crust we live on, the mantle below it, and the core at the center of the planet. It covers mountains and valleys, ocean floors, minerals, and soil. At first glance, it may look still and unchanging. However, over time, the geosphere is anything but static.

Plate tectonics power many of Earth’s major changes. Continents slowly drift apart or collide. Mountains rise, and new ocean basins take shape over millions of years. At the same time, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions remind us that this system is always active. Volcanoes, in particular, connect the deep Earth with the atmosphere. As they erupt, they release gases such as carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide, which can affect climate patterns.

The geosphere also plays a key role in nutrient cycles. As rocks break down through weathering, they release important minerals like calcium, phosphorus, and iron. These nutrients move into rivers and eventually reach the oceans. In turn, they support marine life and entire ecosystems. Meanwhile, this slow weathering process removes carbon dioxide from the air, helping regulate Earth’s climate over long periods.

Soil sits at the boundary between the geosphere and the biosphere. It is more than crushed rock. It is a living system filled with microbes, fungi, and small organisms. Soil stores carbon, filters water, and supports plants and animals on land. At the same time, erosion keeps reshaping Earth’s surface. Wind, water, and human activities all play a role. As a result, landscapes change constantly, influencing how land and the atmosphere interact.

4. Biosphere

The biosphere includes every living organism on Earth and the environments where life exists. It stretches from the deepest ocean trenches to the highest mountain peaks. It spans frozen polar ice and dense tropical rainforests. Life on Earth is incredibly diverse. Millions of species of plants, animals, fungi, and microorganisms live here, and each one plays a role in keeping the planet running.

Living organisms are not just passengers on Earth. They actively shape their surroundings. This constant interaction is known as biosphere dynamics. Plants and photosynthetic microorganisms produce the oxygen we breathe. At the same time, they absorb carbon dioxide. Billions of years ago, this process transformed Earth’s atmosphere and allowed complex life to evolve. Even today, photosynthesis remains powerful. It helps control atmospheric balance and removes around 120 billion tons of carbon from the air every year.

The biosphere also drives Earth’s major biogeochemical cycles. Plants release water vapor through transpiration, which feeds the water cycle and influences local weather. Trees and vegetation slow down rainfall. As a result, they reduce soil erosion and control how water flows across land. Forests go a step further. They create their own microclimates by increasing humidity and stabilizing temperatures.

Microorganisms play a hidden but critical role as well. In soil and water, they power the nitrogen cycle by converting atmospheric nitrogen into forms plants can use. In the oceans, phytoplankton produce vast amounts of oxygen. They also affect cloud formation by releasing tiny particles that help water vapor condense. When these organisms die, they sink to the ocean floor. There, they lock away carbon for hundreds or even thousands of years.

The biosphere clearly shows how Earth’s systems are connected. Living organisms take nutrients from soil and water, build them into their bodies, and return them to the environment through decomposition. Energy from the sun moves through food chains and food webs. With every transfer, life is sustained and heat is released. In this way, living systems stay tightly linked to the chemical and physical world, forming a continuous and dynamic cycle.

Understanding Earth System Interactions

The real power of earth system science lies in understanding how these spheres interact. These interactions create coupled systems where changes in one part trigger cascading effects throughout the planet.

Natural Coupled Systems

Coupled systems are made up of connected parts that constantly affect one another. Each part responds, adjusts, and sends signals back through feedback loops. A clear example is Earth’s atmosphere and ocean. When ocean temperatures change, they alter atmospheric circulation. That shift in the atmosphere then changes ocean currents and heat distribution. Because of this constant back-and-forth, these systems never work alone. They are always exchanging energy and matter.

Feedback mechanisms help explain how these systems behave over time. Feedback happens when a change in one part causes effects in another part. Those effects can either strengthen the original change, called positive feedback, or weaken it, known as negative feedback. The terms can be misleading, though. Positive does not mean beneficial, and negative does not mean harmful. They simply describe whether the change grows or fades.

a. Ice-albedo Feedback

Ice–albedo feedback is a classic example of positive feedback in action. When global temperatures increase, ice and snow begin to melt, especially near the poles. Normally, ice reflects much of the Sun’s energy back into space. This is known as high albedo.

However, once the ice disappears, darker ocean water or land is exposed. These surfaces absorb more sunlight instead of reflecting it. As a result, the absorbed heat raises temperatures even further.

Because of this extra warming, more ice melts. Then the cycle repeats. Each step strengthens the next. Over time, this self-reinforcing loop speeds up warming. That’s why the Arctic is heating up much faster than the global average.

b. Vegetation-climate Feedback

Vegetation–climate feedback includes both positive and negative effects. In the Amazon rainforest, trees release water vapor through transpiration. This moisture helps form clouds and trigger rainfall. The rain then feeds the forest, allowing it to thrive. This cycle creates a positive, reinforcing feedback loop.

However, the balance is fragile. When deforestation removes too many trees, the system starts to break. Less tree cover means less water vapor in the air. As a result, rainfall drops. With less rain, the remaining forest struggles to survive. If this loss crosses a critical point, the ecosystem can shift completely. The lush rainforest may transform into a much drier savanna.

c. Negative Feedback

Negative feedback helps keep systems stable. When something changes, another process pushes back.

Take atmospheric CO₂ as an example. When CO₂ levels rise, many plants grow faster. This is known as the CO₂ fertilization effect. As plants grow more vigorously, they absorb more carbon from the air. As a result, part of the CO₂ increase is naturally reduced.

A similar process happens in the oceans. As temperatures rise, more water evaporates. This extra evaporation can lead to more cloud formation. These clouds send sunlight back into space. In turn, this reflection helps cool the Earth’s surface.

However, cloud feedback is not simple. Different types of clouds behave in different ways. Because of this complexity, scientists are still actively studying how clouds influence climate systems.

Biogeochemical Cycles

Biogeochemical cycles explain how essential elements travel through Earth’s major systems. These movements happen through biological, geological, and chemical processes. Together, they keep life running and help regulate the climate. When we understand these cycles, it becomes clear how matter and energy flow continuously, linking every part of the Earth into one connected system.

1. Carbon Cycle

The carbon cycle gets the most attention, mainly because of its strong link to climate change. Carbon moves through Earth in several forms. It exists in the air as carbon dioxide, in oceans as dissolved carbon, in rocks as fossil fuels and limestone, and in living organisms as organic matter. Plants pull CO₂ from the air during photosynthesis and turn it into sugars and plant tissues. Animals then eat these plants and release CO₂ back into the air through respiration. When plants and animals die, decomposers break them down and return carbon to the soil or atmosphere. Over long periods, some of this carbon becomes buried and slowly transforms into fossil fuels.

Oceans play a huge role in controlling the carbon cycle. They absorb CO₂ directly from the atmosphere through surface exchange. Inside the ocean, phytoplankton use this carbon for photosynthesis. When these tiny organisms die, some of the carbon sinks into deeper waters as dead matter or waste particles. This process, called the biological pump, locks carbon away for hundreds of years. Cold water absorbs more CO₂ than warm water, which is why polar oceans act as major carbon sinks. However, as oceans warm, their ability to absorb carbon decreases. This creates a worrying feedback loop that speeds up climate change.

2. nitrogen cycle

The nitrogen cycle is just as vital because nitrogen is essential for proteins and DNA. Even though nitrogen makes up about 78 percent of the atmosphere, most organisms can’t use it directly. Special bacteria solve this problem. They convert nitrogen gas into ammonia through a process called nitrogen fixation. Other bacteria then turn ammonia into nitrates, which plants can easily absorb. Animals get nitrogen by eating plants or other animals. When organisms die, decomposition returns nitrogen to the soil. Eventually, denitrifying bacteria convert some of this nitrogen back into atmospheric nitrogen, closing the cycle.

Human activity has heavily disrupted the nitrogen cycle. Modern fertilizer production now fixes more nitrogen than all natural processes united. As a result, excess nitrogen often washes into rivers and lakes. This triggers algal blooms and creates dead zones where oxygen levels drop dangerously low. At the same time, nitrogen oxides released from vehicles and factories worsen air pollution and cause acid rain. These effects show how changing one cycle can disturb many Earth systems at once.

3. Phosphorus cycle

The phosphorus cycle works differently from carbon and nitrogen cycles because it has no major atmospheric phase. Phosphorus comes from the weathering of rocks. It enters the soil, where plants absorb it, and then moves through food chains. Eventually, it returns to the soil or flows into the ocean. Over millions of years, phosphorus-rich ocean sediments rise back to land through tectonic movement, restarting the cycle. Because phosphorus is often scarce, it frequently limits plant growth and plays a critical role in agriculture.

4. Water Cycle

The water cycle also counts as a biogeochemical cycle. It links all Earth systems and acts as a transport system for nutrients and pollutants. Water moves quickly through the environment. A raindrop may complete a full evaporation-to-precipitation cycle in about ten days. In contrast, water trapped in glaciers or deep underground can remain there for thousands of years.

These cycles do not work in isolation. They constantly interact with one another. For instance, water availability controls plant growth, which directly affects how much carbon plants can absorb. In the same way, nitrogen availability often limits carbon uptake. Understanding these connections is key to predicting how ecosystems and climate will respond to environmental change.

Case Studies of Sphere Interactions

Practical examples help us to see how Earth’s systems interact. Let’s look at three case studies that show how a change in one sphere can ripple through the whole system.

1: Volcanic Eruptions

When Mount Pinatubo erupted in the Philippines in 1991, it showcased the powerful connections between Earth’s geosphere, atmosphere, and biosphere. The eruption shot massive amounts of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere. There, it reacted with water vapor to form tiny sulfate particles that spread around the globe in just a few weeks.

These particles reflected sunlight back into space, reducing the solar energy reaching Earth’s surface. As a result, global temperatures dropped by about 0.5°C for the next two years. This sudden cooling shifted weather patterns, altering rainfall and storm tracks. Some regions saw declining crop yields due to less sunlight and unpredictable rains.

The eruption also released carbon dioxide and thick ash. Ash settled on plants, blocking sunlight and slowing photosynthesis. It even darkened snow and ice, changing Earth’s reflectivity. Ocean temperatures dropped slightly, affecting marine life.

Mount Pinatubo’s eruption showed just how quickly a single geosphere event can ripple through the atmosphere, oceans, and living systems, impacting life across the planet.

2: El Niño and La Niña

El Niño and La Niña show the Pacific Ocean and atmosphere working together in dramatic ways. Normally, trade winds blow westward, pushing warm surface water toward Asia. This movement allows cold, nutrient-rich water to rise along South America’s coast. The resulting temperature difference across the Pacific shapes weather patterns around the world.

During El Niño, trade winds weaken or even reverse. Warm water drifts east toward South America, and upwelling slows down. This small shift in ocean temperature triggers big global effects. Indonesia and Australia face droughts and wildfires. South America gets heavy rains and floods. North American winters turn warmer and wetter. Even African monsoons weaken, disrupting crops and water supplies.

La Niña is the opposite of El Niño. Trade winds strengthen, and the eastern Pacific cools. This brings wet weather to Asia and Australia but drought to the Americas. These events impact fish populations, harvests, disease outbreaks, and hurricane patterns. They highlight how the ocean and atmosphere connect distant regions, showing just how intertwined Earth’s systems really are.

3: Amazon Deforestation

Deforestation in the Amazon rainforest shows how the biosphere, atmosphere, and hydrosphere are connected—and how tipping points work. Amazon trees release huge amounts of water through transpiration, which creates the rainfall that keeps the forest alive. In other words, trees need rain, and they also make rain—a self-reinforcing cycle.

When forests are cleared for farming, this cycle breaks. Less water vapor reaches the atmosphere, so rainfall drops. Without roots to hold the soil, erosion washes nutrients into rivers and harms water quality. Open soil heats up faster than shaded forest, changing local temperatures. On top of that, cutting trees releases carbon stored in trees and soil, adding to climate change.

Scientists warn that if deforestation passes a critical limit—around 20–25% of the forest—the remaining trees may not produce enough rain to survive. The ecosystem could flip into a drier savanna, releasing massive amounts of carbon and speeding up global warming. This shift would alter weather across South America and possibly beyond, proving that changes in one region of the biosphere can ripple across the globe.

Earth System Models (ESMs) and Predictions

Understanding Earth’s complexity requires powerful tools. Earth System Models are advanced computer programs that simulate how our planet’s spheres—atmosphere, oceans, land, ice, and life—interact. They are essential for predicting future climate, understanding past climate, and testing our knowledge of Earth’s processes.

ESMs evolved from weather forecast and climate models, but they are far more detailed. While traditional climate models mainly focused on atmosphere and ocean physics, ESMs include biogeochemical cycles, vegetation, ice sheets, and even human activity. This holistic approach lets them simulate Earth more realistically.

A typical ESM divides the planet into a three-dimensional grid. Each grid cell contains equations representing natural laws: fluid dynamics for air and water, thermodynamics for energy, chemistry for atmospheric reactions, and biology for ecosystems. The model calculates conditions in each cell over time, showing how the system evolves.

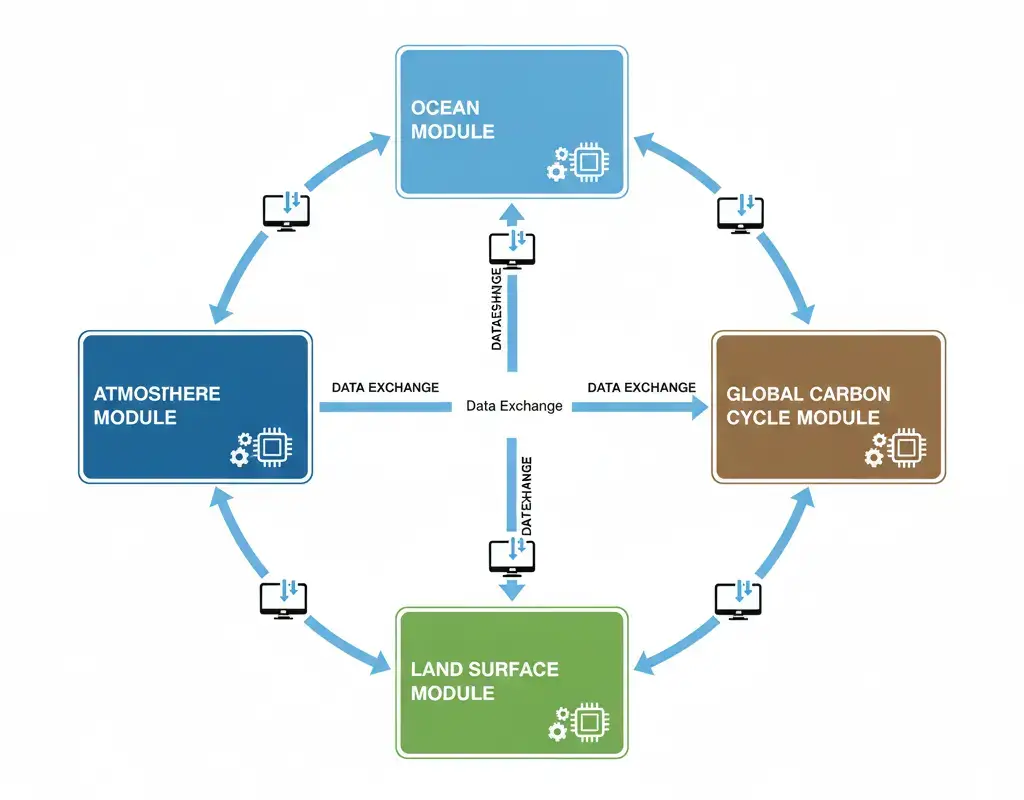

Modern ESMs have multiple components. The atmosphere module tracks temperature, pressure, winds, clouds, and precipitation. The ocean module measures temperature, salinity, and currents. Land modules represent soil moisture, vegetation, and snow cover. Sea ice modules simulate melting and formation. Carbon cycle components track CO₂ absorption by oceans and plants. Some models even include atmospheric chemistry, nitrogen cycles, and dynamic vegetation that adapts to climate.

These components interact continuously. The atmosphere tells the ocean about wind and heat. The ocean responds by sending moisture and heat back. Vegetation absorbs CO₂ and releases water vapor. Each part affects the others, creating feedback loops that mirror real Earth systems.

Scientists test ESMs by simulating past climates and comparing results to real-world observations. If a model can reproduce historical temperature trends, ice ages, or events like El Niño, it boosts confidence in its predictions. However, all models simplify reality. Uncertainty remains, especially around clouds, aerosols, and some feedbacks.

Even so, ESMs have proven accurate. Models from the 1970s and 1980s correctly predicted the warming we see today. Modern models project continued warming if greenhouse gas emissions persist, along with rising seas, shifting rainfall patterns, extreme weather, and ecosystem changes. These predictions guide climate policy and adaptation strategies worldwide.

ESMs also explore tipping points and abrupt changes. They can test scenarios: What happens if the Amazon reaches critical deforestation? How will Atlantic Ocean circulation respond to melting ice? Could feedback loops accelerate warming beyond current predictions? Simulating these scenarios helps identify risks and guide decisions.

Leading research centers run ESMs, including NCAR, NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, and the UK Met Office Hadley Centre. The Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) coordinates global model experiments, allowing scientists to compare results and measure uncertainty across multiple models.

Humans as a Component of Earth Systems

For most of Earth’s 4.5-billion-year history, natural forces shaped the planet. But in the last few centuries, humans have become a powerful force, reshaping Earth’s systems. Our influence is so profound that many scientists say we’ve entered a new geological epoch: the Anthropocene, the age of humans.

The anthroposphere is the sum of human presence and impact. It includes cities, farms, factories, transport networks, and the pollution we create. Unlike natural spheres that evolved slowly over billions of years, the anthroposphere has grown rapidly in just a few centuries, especially since the Industrial Revolution.

Human actions affect all biogeochemical cycles. For example, we’ve increased atmospheric CO2 by 50% since pre-industrial times through burning fossil fuels and clearing forests. This surge in carbon triggers global warming, ocean acidification, and shifting rainfall patterns that affect billions of people.

We’ve also doubled the amount of reactive nitrogen in the environment through fertilizers. While this boosts food production, it also creates dead zones in oceans, pollutes the air, and disrupts ecosystems. The phosphorus cycle is similarly disturbed, with mining and agriculture moving more phosphorus in decades than nature moves in millennia.

Land use changes add another layer of impact. Forests, grasslands, and wetlands are being converted into farms, cities, and roads. About 75% of ice-free land shows human alteration. These changes affect local climates, disrupt water cycles, drive species extinctions, and alter natural feedback loops. When forests are replaced with crops or pavement, less water evaporates, surfaces bounce more sunlight, and carbon storage drops.

Water systems face huge human pressures. We’ve dammed rivers, drained aquifers, and redirected flows for irrigation, industry, and drinking. Some rivers no longer reach the ocean. Groundwater depletion in major farming regions threatens food security and can cause land to sink.

Plastic pollution shows how human-made materials now move through Earth’s systems. Microplastics appear everywhere—from deep oceans to Arctic snow to human blood. They interact with air, water, and soil, affect organisms, may even influence clouds, and can last for centuries.

The challenge of sustainability is understanding these interactions. Can we meet human needs while keeping Earth’s systems healthy? We must recognize feedback loops. Some are worrying: warming permafrost releases methane, forest loss reduces rainfall, ocean warming slows CO2 absorption. Others offer hope: renewable energy cuts emissions, reforestation captures carbon, regenerative farming improves soil health.

Earth system science helps us see these connections. It shows how energy choices change oceans, how farming alters the atmosphere, and how urban design affects local climate. Understanding these links is key to solutions that work with Earth’s systems, not against them.

Theoretical Perspectives and Historical Foundations

Earth system science didn’t appear out of nowhere. It grew from centuries of scientific exploration. Key ideas and visionary thinkers shaped this exploration. They laid the foundation for our modern understanding of the planet as a connected whole.

In the 1970s, James Lovelock and microbiologist Lynn Margulis proposed the Gaia hypothesis. This idea was bold and controversial. It suggested that Earth acts as a self-regulating system, with life actively maintaining conditions that support life. Named after the Greek Earth goddess, Gaia highlighted that organisms don’t just adapt to their environment—they modify it to keep the planet habitable.

For instance, ocean algae release dimethyl sulfide (DMS), which helps form clouds. More clouds reflect sunlight, cooling the Earth’s surface. Similarly, life has maintained atmospheric oxygen at about 21% for hundreds of millions of years. This level is high enough for complex life. It is also low enough to avoid runaway fires. The idea of Earth as a conscious organism is still debated. However, the central insight—that life shapes planetary conditions—is now a cornerstone of earth system science.

Long before Gaia, other thinkers set the stage for this systems perspective. In the early 20th century, Russian scientist Vladimir Vernadsky introduced the concept of the biosphere. He realized that life wasn’t separate from geology or chemistry but played a crucial role in shaping Earth’s surface and atmosphere.

Back in the 1800s, Alexander von Humboldt explored South America and noticed how climate, vegetation, and geography were interconnected. He saw nature as a web of relationships rather than isolated pieces. His holistic vision was ahead of its time and foreshadowed the integrated approach of modern earth system science.

The mid-20th century brought systems theory, giving scientists tools to study complex interactions mathematically and conceptually. Ideas like feedback loops, steady states, and dynamic equilibrium helped researchers see Earth not as separate parts, but as a single, interconnected system.

The space age accelerated this shift. Satellites gave us a global view, showing atmospheric circulation, ocean currents, ice coverage, and vegetation patterns all at once. The iconic “Earthrise” photo from Apollo 8 in 1968 captured a planet without borders—a single, dynamic system. This image mirrored the emerging scientific perspective.

By the 1980s, NASA formalized earth system science with its Earth System Sciences Committee. The goal was clear: understanding Earth required linking formerly separate disciplines. Climate scientists collaborated with biologists, oceanographers with geochemists. The committee emphasized global observations and computer modeling to grasp the planet’s complexity.

The discovery of the ozone hole in the 1980s showcased the power of this approach. Scientists found that human-made chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were destroying the stratospheric ozone layer, increasing UV radiation at the surface. This problem spanned chemistry, biology, and atmospheric science. The Montreal Protocol, which phased out CFCs, proved that understanding Earth’s interconnected systems can guide effective global policy.

Today, earth system science keeps expanding. It now includes social sciences, recognizing that human choices drive many planetary changes. Complexity science helps study how small actions can trigger large shifts. Advanced models use ever-growing data from satellites, ocean buoys, and ground stations. This data reveals our planet’s intricate, living system more clearly than ever.

Conclusion

Earth system science reveals a planet of stunning complexity and seamless connection. The atmosphere, hydrosphere, geosphere, and biosphere aren’t separate—they are deeply linked. Energy and matter flow continuously between them, shaping the dynamic, habitable world we live in.

We’ve seen how feedback loops can amplify or dampen changes and how biogeochemical cycles tie the living and non-living together. Events in one sphere ripple through the others. Volcanic eruptions can cool the planet. Ocean currents steer continental climates. Forests can even make their own rain. Each example shows the hidden dynamics that only appear when we study Earth as a whole system.

Earth system models help us explore these complex interactions. They let us simulate changes, test ideas, and predict future outcomes. While uncertainty remains, these tools are essential for understanding climate change and guiding action. As models improve and observations grow, we gain more power to foresee how Earth behaves.

Humans have become a planetary force, touching every sphere through our activities. This brings both responsibility and opportunity. Climate change, ecosystem loss, and resource pressures are real challenges. Yet, seeing Earth as a system also points us toward solutions. We can spot leverage points where small actions trigger positive effects. We can work with nature instead of against it.

The greatest lesson of Earth system science is interconnection. Nothing exists alone. Decisions about energy affect not just the atmosphere but oceans, ice, ecosystems, and communities. Understanding these links is the first step toward sustainability and responsible stewardship of our shared planet.

Our journey to understand Earth continues. Every satellite launched, every dataset collected, every model refined adds to our knowledge. As you move forward, notice the connections around you—how weather shapes vegetation, how land use changes local climates, how human choices ripple through systems. You’re not just observing Earth; you’re part of its vast, interconnected dance.

Recommended Resources for Curious Minds

Ready to explore Earth system science in depth? These handpicked resources will boost your understanding and give you practical, hands-on learning experiences.

1. Earth System Science: A Very Short Introduction

This accessible book by Tim Lenton provides a comprehensive yet concise overview of earth system science, perfect for students and anyone seeking a solid foundation in how our planet’s spheres interact and influence global processes.

Excellent for: Beginners wanting clear explanations without overwhelming technical detail

2. The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision

Fritjof Capra and Pier Luigi Luisi explore systems thinking applied to life and Earth, bridging biology, ecology, and earth science. This book deepens understanding of how interconnected systems function at multiple scales.

Excellent for: Readers interested in the philosophical and scientific foundations of systems thinking

3. Earth Science Lab Kit for Students

Hands-on learning brings earth system concepts to life. This lab kit includes materials for experiments on rock cycles, water filtration, weathering, and more, making abstract concepts tangible for students and hobbyists.

Excellent for: Educators, parents, and students wanting practical earth science exploration

4. This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate

Naomi Klein examines the human dimensions of earth system changes, exploring how social, economic, and political systems interact with planetary processes and what it means for addressing climate challenges.

Excellent for: Understanding the intersection of human systems and Earth system science

Transparency note: The links above are affiliate links. If you purchase through them, we may earn a small commission at no additional cost to you. We only recommend resources we genuinely believe enhance learning about earth system science.