Imagine if building the perfect neural network didn’t demand years of experience or endless trial and error. Neural Architecture Search is making that idea real. It automates the way machine learning models are designed. Instead of manually adjusting layers, connections, and hyperparameters, NAS explores thousands of possible architectures on its own. The goal is simple: find the best design for a specific task.

For a long time, neural network design has been both an art and a science. Engineers relied heavily on intuition, experience, and repeated experiments. However, as models became deeper and systems more demanding, this manual process started to fall short. At this point, NAS steps in and changes the approach entirely. It treats network design as an optimization problem—one that machines can systematically solve.

This shift marks a major milestone in the evolution of AutoML. By automating one of the hardest parts of model development, NAS lowers the barrier to advanced machine learning. As a result, more people and organizations can build powerful models faster. Whether the goal is higher accuracy, faster inference, or better efficiency on edge devices, NAS provides a clear and structured path forward.

The benefits go far beyond saving time. In fact, NAS has already produced architectures that outperform human-designed models on benchmarks like ImageNet. Even more impressive, many of these models use fewer parameters and run faster. By exploring design combinations humans might never think of, NAS doesn’t just replicate expert knowledge—it often pushes past it.

Neural Architecture Search Core Concepts Explained

Understanding neural architecture search starts with three core components that work together to automate model design. These elements act as the foundation of every NAS algorithm. No matter the method, each approach builds on these same basics.

Search Space: Defining Architectural Possibilities

The search space defines which architectures NAS is allowed to explore. Think of it like a vocabulary. NAS uses this vocabulary to build neural networks, just like words form sentences. If the search space is too small, creativity suffers. New and better designs get missed. On the other hand, if it’s too large, the search quickly becomes expensive and slow. So, a good search space finds the sweet spot. It stays expressive, yet manageable.

Primitives are the basic building blocks inside this space. These blocks tell NAS what it can use while designing a network. Common primitives include convolution layers with different kernel sizes, pooling layers, skip connections, and attention modules. Today’s search spaces go even further. They often include advanced operations like depthwise separable convolutions and inverted residual blocks. These choices matter because they are already proven to work well in manually designed models.

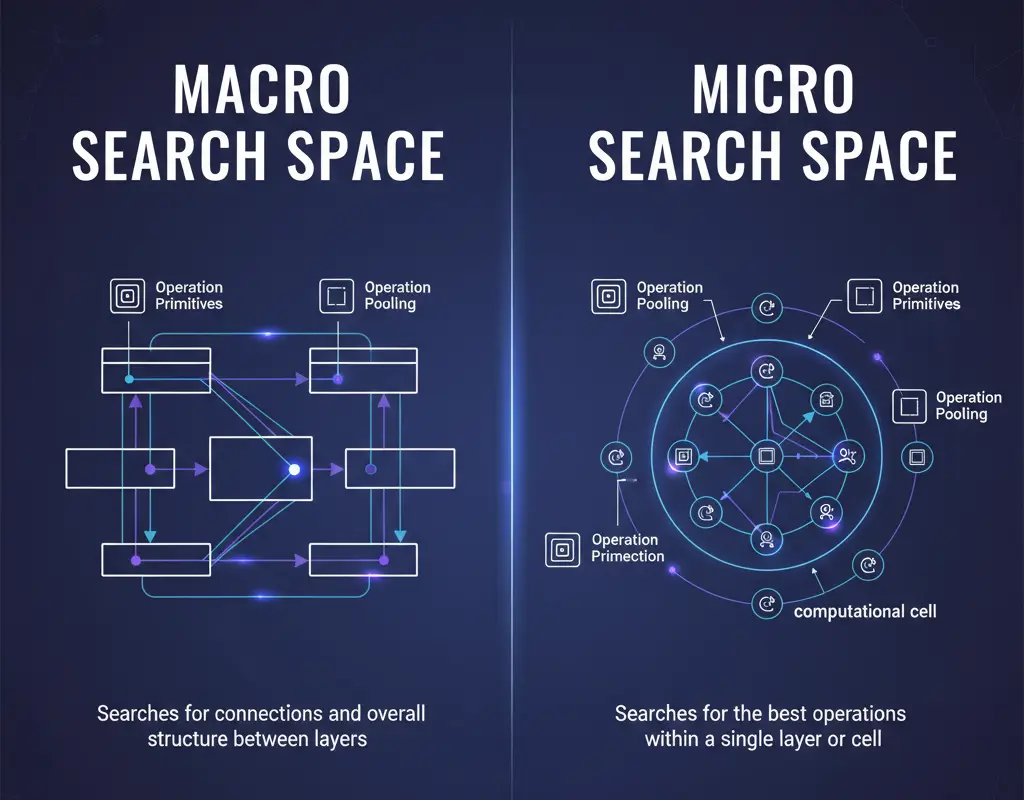

Search spaces can be divided into macro and micro levels. The macro search space looks at the big picture. It decides how many layers the network should have, how blocks connect, and how information flows overall. In contrast, the micro search space zooms in. It focuses on designing small units, called cells, that are repeated again and again across the network.

This cell-based idea became popular with models like NASNet. It works well because NAS searches a smaller space first. Then, it reuses the best cell design to build larger networks. As a result, you still get diverse architectures without exploding the search cost.

In practice, a macro search might allow anywhere from 5 to 20 layers with flexible connection patterns. A micro search, however, finds one strong cell and stacks it multiple times using fixed rules. Both strategies have clear trade-offs. Macro search gives more freedom but grows exponentially harder to explore. Micro search is faster and more efficient, but it limits variety due to repetition.

In short, the choice between macro and micro search depends on your goals. Do you want maximum flexibility, or faster and cheaper discovery? The right answer often lies somewhere in between.

Search Strategies: How Algorithms Explore Architecture Space

Once you know what can be built, the next step is figuring out how to search that space smartly. This is where NAS methods really start to differ. Each approach follows a unique strategy and demands a different level of computational power.

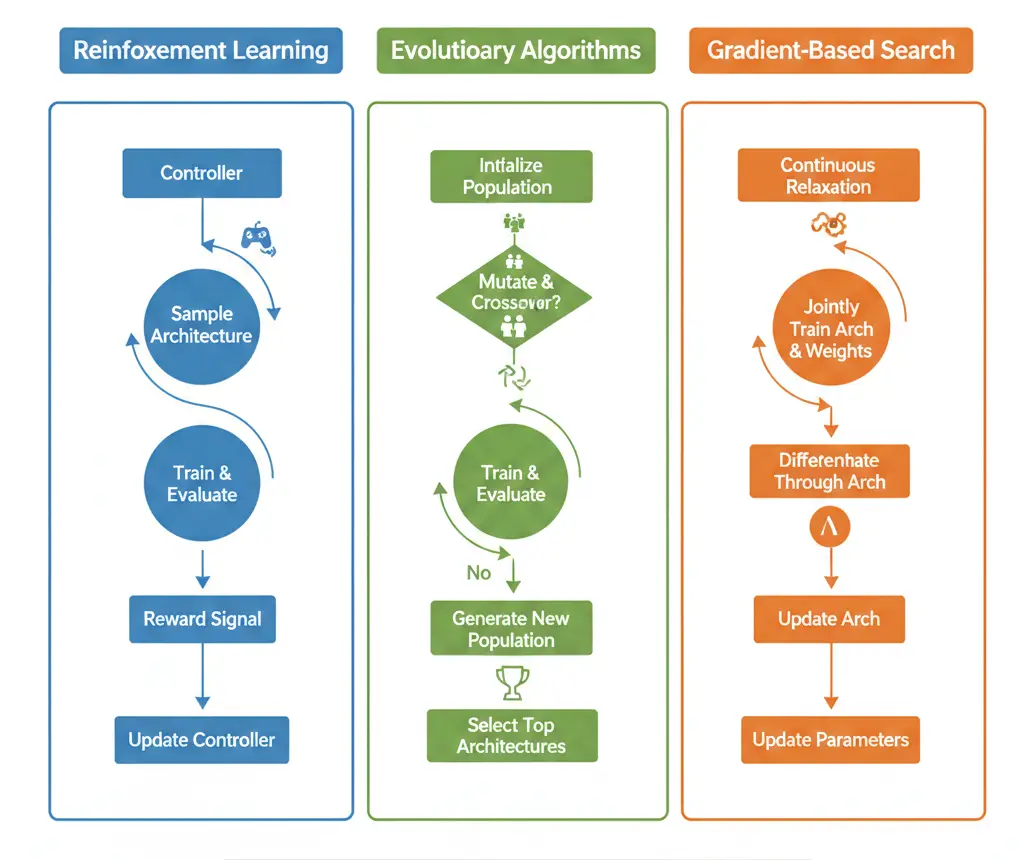

Reinforcement learning–based NAS frames architecture search as a step-by-step decision process. Here, an agent—often a recurrent neural network—builds a model layer by layer. After generating an architecture, the model is trained and evaluated. Its validation performance then becomes a reward signal. Over time, the agent learns which design choices lead to better results. Google’s original NAS work followed this path, using a controller RNN to predict layers and connections. Although this method is effective, it comes at a high cost. Thousands of candidate networks must be fully trained, which makes it extremely resource-intensive.

Evolutionary approaches borrow ideas from natural selection. Instead of a single agent, they work with a population of architectures. Each one is evaluated for performance, and the strongest candidates are kept. New architectures are then created through mutations and crossovers. For example, a mutation might change a layer type or add a skip connection, while crossover mixes parts of two strong models. Methods like AmoebaNet have produced impressive results. However, they still rely on heavy computation to explore the search space.

Gradient-based NAS marks a major shift toward efficiency. Rather than making hard, discrete choices, these methods turn the search space into a continuous one. Techniques like DARTS assign learnable weights to all possible operations. During training, gradient descent naturally increases the importance of useful operations and suppresses weaker ones. Because this process uses standard backpropagation, it dramatically cuts search time. What once took thousands of GPU days can now be done in just a few. In the end, the final architecture is formed by selecting the operations with the highest learned weights.

Overall, the key difference between these NAS strategies lies in how they balance search power and efficiency. Some aim for maximum flexibility, while others focus on speed and practicality.

Performance Estimation: Evaluating Architectures Efficiently

The most expensive part of Neural Architecture Search is figuring out how good each candidate model really is. Training every architecture from scratch on a full dataset would take way too much time and compute. That’s why performance estimation techniques exist. They give faster, smarter ways to judge model quality without full training.

Weight sharing is one of the biggest efficiency boosters in NAS. Instead of training each architecture separately, a single supernet is trained that contains all possible architectures in the search space. Individual models, often called child architectures, reuse the supernet’s weights. This lets us estimate performance quickly, without starting from zero every time. One-shot NAS pushes this idea even further. The supernet is trained only once, and many architectures are sampled and evaluated using the same shared weights.

Another popular speed-up strategy is using proxy tasks. Rather than training on the full dataset for many epochs, architectures are tested on smaller datasets, trained for fewer epochs, or evaluated using lower-resolution images. The key assumption here is simple: if one architecture performs better than another on the proxy task, it will likely do the same on the full task. This isn’t always perfect, but the massive reduction in compute often makes the trade-off worth it.

Performance predictors take an even more radical approach. They skip training altogether. Instead, a machine learning model is trained to predict how well an architecture will perform based on its structure. After fully evaluating a small set of architectures, this predictor learns patterns from them. Models like graph neural networks can even treat architectures as graphs and estimate their performance directly. While this approach is promising, it must be used carefully. Without proper validation, predictors can overfit to quirks in the search space rather than true performance signals.

Overall, these techniques make NAS practical at scale. They trade a bit of precision for massive gains in speed, and in most cases, that’s a smart deal.

Popular NAS Techniques & How They Work

The field has moved fast. Each new technique builds on the last and fixes what didn’t work before. As a result, progress keeps accelerating. By understanding these methods, you can clearly see how automated architecture design has become smarter, faster, and more efficient over time.

Reinforcement Learning NAS

Google’s landmark 2017 NAS paper changed how researchers thought about model design. It was one of the first to apply reinforcement learning to neural architecture search, and it set the blueprint for many methods that followed.

At the core of this approach is a controller network, built using an LSTM. Its job is simple but powerful: generate neural network architectures as a sequence of tokens. Each token represents one design choice.

The process unfolds step by step. First, the controller selects the operation for layer one. Next, it chooses the layer’s parameters. Then it decides whether to add a skip connection. This continues until a full architecture is defined. Once complete, the architecture is built and trained on the target task until it converges.

After training, the model’s validation accuracy is measured. This score becomes the reward signal. The controller then updates itself using the REINFORCE policy gradient algorithm. In other words, better architectures lead to stronger rewards, and the controller learns from them.

Over thousands of iterations, clear patterns start to emerge. In the early stages, the controller explores almost randomly. But as learning progresses, it shifts toward exploitation. It begins favoring proven ideas, such as skip connections or effective layer sequences. As a result, the generated architectures grow more refined and more powerful.

This strategy led to the discovery of NASNet, which achieved state-of-the-art performance on ImageNet. However, there was a catch. The computational cost was massive. The original search consumed around 800 GPUs for several weeks. Because of this, researchers quickly turned their attention to finding faster and more efficient NAS alternatives.

Evolutionary NAS

Evolution-based methods bring genetic algorithm principles to architecture search. AmoebaNet demonstrated that evolutionary approaches could match reinforcement learning’s performance while offering simpler implementation and better parallelization.

The process begins with a population of randomly initialized architectures. Each generation evaluates all architectures in the population on the target task. The top performers survive to the next generation, while lower-performing architectures are discarded. New architectures are created through mutations of survivors.

Mutations might include changing a layer type (convolution to pooling), altering kernel sizes, adding or removing connections, or adjusting the number of filters. Some implementations also use crossover, combining components from two parent architectures to create offspring that inherit features from both.

The key advantage over reinforcement learning is simplicity—no controller to train, just survival of the fittest. The parallel nature also scales well across compute clusters. However, evolution still requires training many candidate networks, limiting efficiency gains.

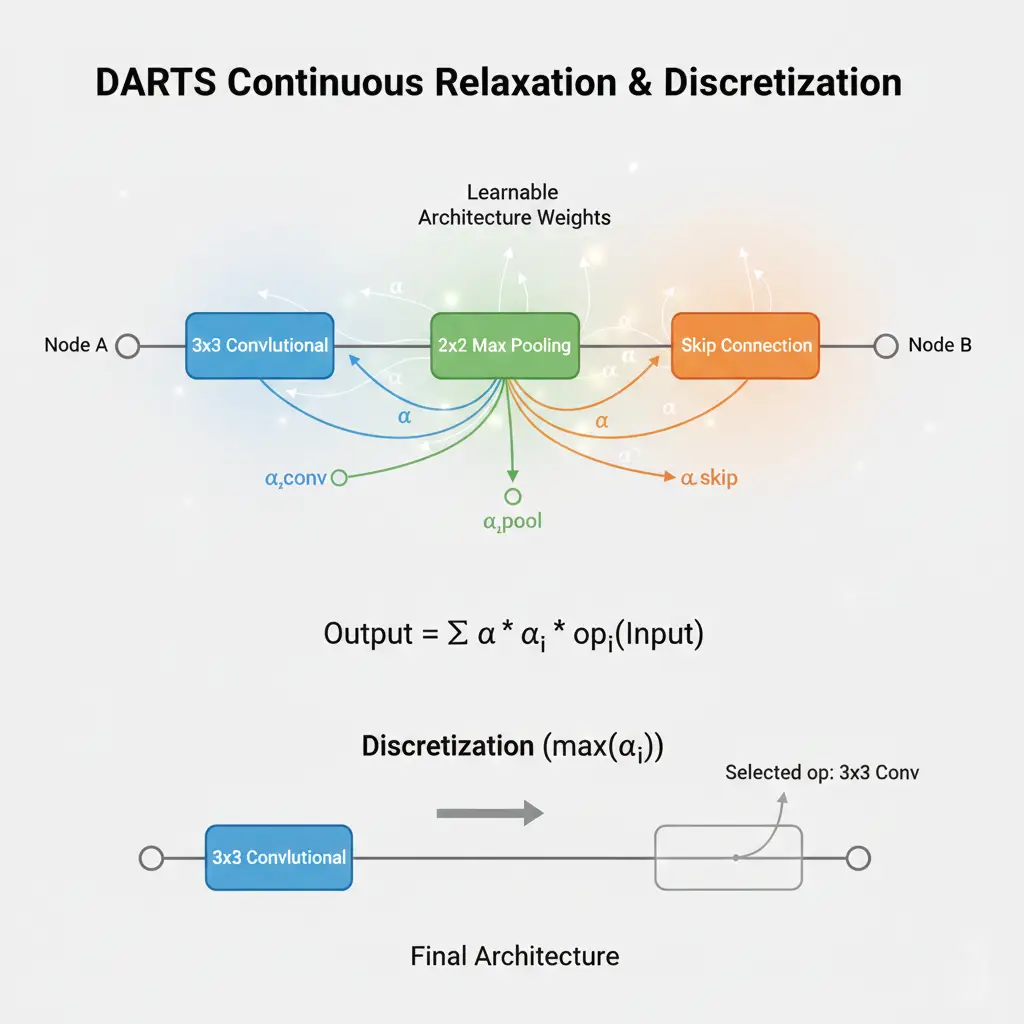

Differentiable NAS (DARTS)

DARTS (Differentiable Architecture Search) represents a paradigm shift in NAS efficiency. By making architecture search differentiable, it reduces search costs from thousands of GPU days to just a few GPU days—a 1000x speedup.

The core insight is treating architecture search as a continuous optimization problem. Instead of discrete choices (use convolution OR pooling), DARTS creates a mixed operation that’s a weighted combination of all possible operations. Each edge in the computational graph computes:

o(x) = Σ (exp(α_i) / Σexp(α_j)) * operation_i(x)

The architecture parameters α determine the mixing weights via softmax. During search, both network weights and architecture parameters are optimized jointly through gradient descent. Architecture parameters learn which operations are most beneficial, while network weights learn how to use those operations effectively.

After search completes, the discrete architecture is derived by selecting the operation with the highest weight on each edge. This discretization step introduces some performance gap—the continuous relaxation doesn’t perfectly match the discrete architecture—but the efficiency gains far outweigh this limitation.

DARTS has inspired numerous variants addressing its limitations, like PC-DARTS (partial channel connections for memory efficiency) and GDAS (sampling instead of softmax mixing). The differentiable approach has become one of the most popular NAS paradigms.

One-Shot and Weight Sharing Models

One-shot NAS takes weight sharing to its logical extreme: train a single supernet that contains all possible architectures as subnetworks, then derive child architectures by sampling from this supernet without additional training.

The supernet acts as a universal architecture representation. During training, you randomly sample different paths through the supernet, ensuring all operations receive gradient updates. After supernet training completes, you can instantly evaluate any architecture in the search space by inheriting the corresponding weights.

ENAS (Efficient Neural Architecture Search) pioneered this direction, sharing weights between child models to reduce search costs dramatically. Single-Path One-Shot NAS refined the approach by training the supernet with uniform path sampling and using evolutionary search over the trained supernet to find optimal architectures.

The critical assumption is that weights trained in the supernet context transfer well to standalone architectures. While not perfectly accurate—weight coupling effects can mislead rankings—one-shot methods achieve remarkable efficiency. Search times drop from days to hours, making NAS accessible to researchers without massive compute budgets.

Zero-Cost and Training-Free Scoring

The newest frontier in NAS efficiency eliminates training entirely during search. Zero-cost proxies evaluate architecture quality using metrics computed from the randomly initialized network, before any training occurs.

These proxies analyze properties like gradient flow, activation patterns, or expressivity at initialization. For example, one metric measures how well gradients propagate through the network by checking if the gradient norm remains stable across layers. Another examines the linear regions created by the network’s activation functions—more expressivity at initialization may indicate better learning capacity.

Methods like TE-NAS and ZiCo demonstrate that carefully chosen zero-cost proxies can rank architectures surprisingly well, correlating strongly with post-training performance. A single forward and backward pass through each candidate—taking milliseconds—provides enough signal to identify promising architectures.

The computational savings are extraordinary: full NAS searches can complete in minutes rather than days. However, zero-cost methods remain an active research area. The proxies don’t always generalize across different search spaces or tasks, and their theoretical foundations are still being established. When they work well, though, they represent the ultimate in NAS efficiency.

Essential Tools & Frameworks for Implementing Neural Architecture Search

Putting NAS into practice requires robust software infrastructure. Several frameworks have emerged to make neural architecture search accessible to practitioners.

NASLib (PyTorch)

NASLib provides a modular, research-friendly framework for implementing and comparing NAS algorithms. Built on PyTorch, it separates search spaces, search strategies, and performance estimation into independent components you can mix and match.

The library includes implementations of popular search spaces like DARTS, NAS-Bench-201, and custom macro spaces. Search strategies range from random search and evolution to differentiable methods and one-shot approaches. This modularity lets researchers test new ideas without reimplementing everything from scratch.

NASLib particularly excels at reproducibility. It integrates with NAS benchmark datasets, ensuring fair comparisons across methods. The codebase emphasizes clean abstractions—you can add a new search strategy by implementing a single class that inherits from the base SearchStrategy template.

For practitioners, NASLib offers pre-trained supernets and quick-start guides for common scenarios. You can run DARTS search on your custom dataset with just a few lines of configuration. The framework handles the complexity of weight sharing, architecture encoding, and performance tracking behind the scenes.

NNI (Microsoft)

Neural Network Intelligence from Microsoft takes a more production-oriented approach. NNI provides a comprehensive AutoML toolkit that includes NAS alongside hyperparameter optimization, feature engineering, and model compression.

The framework’s strength lies in its flexibility and distributed training support. You can run NAS experiments across multiple GPUs or even multiple machines using various search algorithms. Built-in support for popular methods like ENAS, DARTS, and SPOS makes it easy to get started.

NNI uses a trainer-advisor architecture. The trainer executes actual model training and evaluation, while the advisor implements the search strategy that generates new architecture candidates. This separation allows mixing trainers (PyTorch, TensorFlow, or custom) with different advisors without code conflicts.

The web UI provides real-time monitoring of search progress, showing performance metrics for all tried architectures. You can pause, resume, or adjust search parameters mid-run. For practitioners managing multiple experiments, this visibility proves invaluable.

AutoKeras and SageMaker Autopilot

For users seeking maximum simplicity, higher-level AutoML platforms abstract NAS details entirely. AutoKeras wraps NAS into a scikit-learn-like API where you call fit() and the library handles architecture search automatically.

AutoKeras is ideal for rapid prototyping. With minimal code, you can search for optimal architectures for image classification, text classification, or structured data tasks. The library makes reasonable default choices for search spaces and strategies, letting you focus on problem formulation rather than NAS mechanics.

AWS SageMaker Autopilot provides similar convenience at enterprise scale. It automatically performs NAS and hyperparameter optimization on your dataset, handling infrastructure provisioning and distributed training. While you sacrifice control over the search process, you gain integration with AWS’s ML ecosystem and professional support.

These platforms democratize NAS by removing barriers to entry. A data scientist unfamiliar with architecture search can still leverage its benefits. The trade-off is less customization—you can’t easily implement novel search strategies or spaces—but for many applications, the built-in capabilities suffice.

Standard Benchmarks and Evaluation Strategies in Neural Architecture Search

As NAS research exploded, comparing methods became challenging. Different papers used different search spaces, datasets, and evaluation protocols, making apples-to-apples comparisons nearly impossible. Benchmark datasets emerged to solve this reproducibility crisis.

NAS-Bench-101 and Beyond

NAS-Bench-101, released by Google Research, pre-computed the performance of 423,624 unique neural network architectures trained on CIFAR-10. Each architecture in the benchmark has been trained multiple times with different random seeds, and the results are tabulated in a queryable database.

This changes the game for NAS research. Instead of training each candidate architecture—the most expensive part of NAS—you simply look up its performance in the benchmark. A NAS algorithm that previously required days to evaluate can now be tested in minutes. Researchers can iterate on search strategies rapidly, confident that performance comparisons are fair.

The benchmark defines a specific search space of convolutional architectures with a maximum of 9 operations. While this limits the diversity of architectures, it provides a controlled environment for studying search algorithms themselves. You can isolate the effectiveness of a search strategy from other factors like search space design or training procedures.

NAS-Bench-201 expanded the concept with a different search space and multiple datasets (CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and ImageNet-16-120). It includes 6,466 unique architectures, each trained 3 times per dataset with different seeds. This multi-dataset evaluation reveals how well search strategies generalize across tasks.

Other benchmarks have emerged for specific domains: TransNAS-Bench for transformer architectures, NAS-Bench-NLP for language models, and hardware-aware benchmarks that include latency and energy consumption metrics alongside accuracy.

How Benchmarks Improve Research Comparisons

Beyond efficiency, benchmarks ensure reproducibility and fair comparison. Too often, NAS papers reported impressive results that others couldn’t replicate due to subtle differences in training procedures, data augmentation, or even random seeds.

Benchmarks eliminate these confounding variables. When everyone queries the same database, the only difference between methods is the search algorithm itself. This clarity accelerates progress by letting researchers identify what actually works.

The benchmarks also enable meta-analysis of NAS methods. Researchers have used them to study questions like: How much does search budget matter? Do more complex search strategies outperform random search? What makes certain search spaces easier to optimize than others?

One surprising finding from benchmark studies is that simple random search often performs better than expected, especially with limited search budgets. This highlights the importance of search space design—a well-designed space lets even naive search strategies find good architectures. The interaction between search space and strategy proves more subtle than initially assumed.

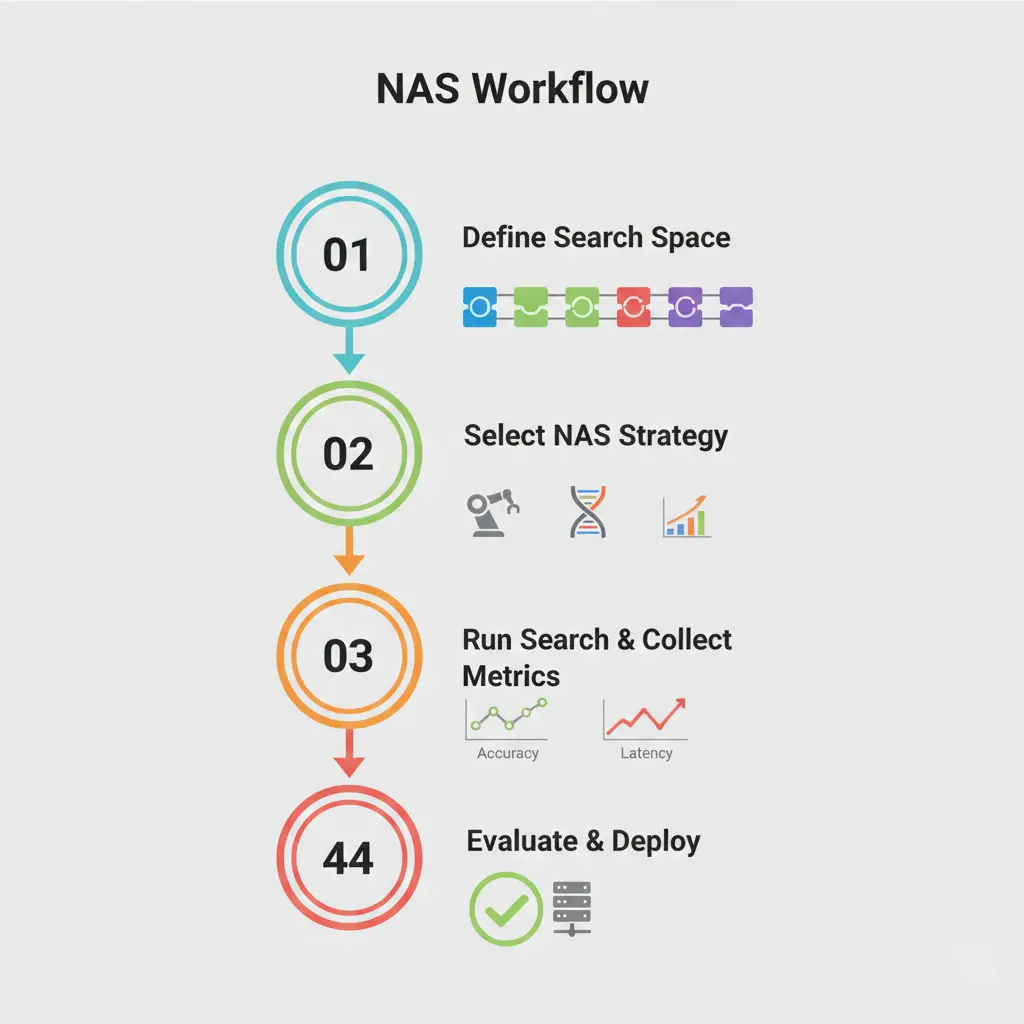

Practical Workflow for Neural Architecture Search

Moving from theory to practice requires a systematic approach. Here’s a step-by-step workflow for applying NAS to your machine learning problem.

Step 1: Define Your Search Space

Start by deciding what architectural choices matter for your problem. Are you working with images, text, or structured data? What operations are candidates—standard convolutions, depth-wise separable convolutions, attention mechanisms?

Consider both macro and micro design. If compute is limited, a micro search space with cell-based repetition provides efficiency. If you need maximum flexibility for a novel task, a macro space might be worth the extra cost.

Include domain knowledge in your search space design. For image classification, include operations proven effective in computer vision like skip connections and batch normalization. For sequence modeling, ensure recurrent or attention-based components are available.

Balance between expressiveness and tractability. A search space with 10^20 possible architectures might contain the perfect solution, but you’ll never find it. Constraint the space to architectures that make structural sense—ensure proper tensor shape compatibility, avoid dead-end paths, and enforce reasonable parameter budgets.

Step 2: Select Your NAS Strategy

Your choice of search strategy should align with your computational budget and timeline. If you have access to significant compute resources and need state-of-the-art results, reinforcement learning or evolutionary methods remain competitive despite higher costs.

For most practical applications, differentiable NAS or one-shot methods offer the best balance. DARTS-based approaches work well when you can afford a few GPU days for search. One-shot methods shine when you need results faster or are working with limited hardware.

Zero-cost proxies merit consideration for rapid prototyping or when searching repeatedly on similar tasks. They’re particularly useful for ablation studies where you’re testing many variations of your search space or objective.

Consider your familiarity with the methods. DARTS has more published research and debugging resources than newer techniques. Starting with well-established methods reduces implementation headaches, even if cutting-edge approaches promise better theoretical properties.

Step 3: Run Search and Collect Metrics

Execute your NAS algorithm with careful monitoring. Track not just accuracy but also the diversity of explored architectures. If your search keeps proposing similar networks, you might be stuck in a local optimum or your search space might be too constrained.

Log comprehensive metrics during search: validation accuracy, training time per architecture, parameter counts, and FLOPs (floating-point operations). These secondary metrics help you understand trade-offs. The highest-accuracy architecture might have 10x more parameters than the second-best, making it impractical for deployment.

Be prepared for the search to take time, even with efficient methods. A DARTS search might take 4-8 GPU days; evolutionary or RL-based searches can take weeks. Plan your timeline accordingly and start with smaller proxy tasks to debug your setup before committing to full-scale search.

Consider early stopping criteria. You don’t always need to exhaust your search budget. If architecture performance plateaus—no improvement in the best architecture for many iterations—you can stop early and proceed to evaluation.

Step 4: Evaluate and Deploy the Best Architecture

Once search completes, train the discovered architecture from scratch on your full dataset. This step is critical—performance during search (especially with weight sharing) doesn’t perfectly predict standalone performance.

Train multiple runs with different random seeds to assess stability. The best architecture should consistently outperform baselines, not just succeed due to lucky initialization. Standard deviations give you confidence intervals for the improvement.

Compare against human-designed baselines appropriate for your task. If NAS found an architecture only marginally better than ResNet-50, question whether the search was worth the effort. Substantial improvements (3-5+ percentage points on accuracy, or 2x speedups at similar accuracy) justify the NAS investment.

Consider post-search optimization. You might apply neural architecture optimization techniques like pruning or quantization to the discovered architecture. Sometimes NAS finds architectures that are particularly amenable to compression, achieving even better efficiency after post-processing.

Finally, document your discovered architecture thoroughly. Visualize it, describe its key features, and preserve the configuration for reproducibility. Future projects might benefit from using your architecture as a starting point rather than searching from scratch.

Neural Architecture Search in Action: Case Studies of Automated Model Design

Real-world applications demonstrate NAS’s transformative potential across different domains and constraints.

NAS in Computer Vision

The ImageNet classification benchmark has been the proving ground for NAS methods since the beginning. Google’s original NASNet achieved state-of-the-art accuracy while using fewer parameters than hand-designed networks, marking a watershed moment for automated design.

EfficientNet took this further by jointly optimizing for accuracy and efficiency. Using NAS to determine optimal network depth, width, and resolution simultaneously, it discovered architectures that significantly outperformed previous models across the entire efficiency spectrum. The scaling rules learned from NAS transferred across different compute budgets, making EfficientNet-B0 through B7 the go-to architectures for practitioners with varying resource constraints.

In object detection and segmentation, NAS has proven equally transformative. NAS-FPN discovered feature pyramid network architectures for object detection that outperformed hand-designed alternatives. Auto-DeepLab applied NAS to semantic segmentation, searching over both the network backbone and the decoder structure simultaneously.

These vision successes share common themes: NAS excels at discovering intricate patterns of layer connections and operation sequences that humans might miss. Skip connections at unexpected network depths, asymmetric encoder-decoder structures, and novel feature fusion patterns emerge from automated search.

NAS for NLP and Transformer Architectures

Natural language processing presents different challenges than vision. Transformers dominate the field, but their architecture contains many design choices: number of layers, attention heads, hidden dimensions, and even whether to share parameters across layers.

Evolved Transformer used evolution-based NAS to improve upon the original Transformer architecture, discovering modifications that enhanced translation quality. The search found benefits in architectural details like where to place normalization layers, how to structure feed-forward networks, and optimal attention patterns.

More recently, NAS has tackled language model efficiency. As models scale to billions of parameters, architecture choices dramatically impact training cost and inference speed. NAS methods have discovered compressed architectures that maintain performance while reducing parameters or using more efficient attention patterns.

Hardware-aware NAS proves particularly valuable for deploying NLP models on edge devices. Searching jointly for accuracy and latency on target hardware (like smartphones or embedded systems) yields architectures that maintain quality while meeting strict inference time budgets. These hardware-aware approaches consider device-specific factors like memory bandwidth and CPU cache sizes during search.

Hardware-Aware NAS: Optimizing for Real-World Deployment

Accuracy alone doesn’t determine success in production systems. Latency, energy consumption, and memory footprint often matter just as much. Hardware-aware NAS incorporates these metrics directly into the search objective.

ProxylessNAS demonstrated this approach by searching for efficient architectures specifically for mobile deployment. Rather than optimizing accuracy alone, it balanced accuracy against latency measured on actual mobile devices. The resulting architectures achieved better accuracy-latency trade-offs than models designed purely for accuracy.

Once for All took hardware-awareness further by training a single supernet that supports diverse deployment scenarios. From this supernet, you can extract sub-networks optimized for different hardware platforms—high-end GPUs, mobile phones, or microcontrollers—without additional training. This “train once, deploy anywhere” paradigm dramatically reduces the cost of supporting multiple deployment targets.

Energy-aware NAS addresses sustainability concerns. Training and running neural networks consumes significant energy, contributing to carbon emissions. By incorporating energy consumption into the search objective, NAS can discover architectures that maintain performance while reducing computational demands. Some methods have achieved 50% energy reductions compared to baseline architectures with minimal accuracy loss.

Technical Challenges and Practical Limitations of Neural Architecture Search

Despite remarkable progress, NAS faces several persistent challenges that temper its adoption and effectiveness.

Computational Cost and Environmental Impact

While modern NAS methods are far more efficient than early approaches, the computational requirements remain substantial. Even DARTS requires multiple GPUs running for days. For organizations without significant compute infrastructure, this creates a barrier to entry.

The environmental impact deserves serious consideration. Training thousands of neural networks during architecture search consumes enormous energy. One study estimated that NAS searches can produce carbon emissions equivalent to several transcontinental flights. As climate concerns intensify, the ML community must weigh the benefits of automated design against its ecological footprint.

Some argue that NAS’s one-time search cost pays dividends when the discovered architecture is deployed millions of times. If an efficient architecture saves energy on every inference, the upfront search cost amortizes. However, this logic only applies when the discovered architecture sees widespread use, not for project-specific searches.

Efficiency research aims to reduce these costs further. Zero-cost proxies, when reliable, drop search costs by orders of magnitude. Transfer learning approaches let you start from architectures discovered on similar tasks rather than searching from scratch. These directions help make NAS more sustainable.

Security Vulnerabilities

Recent research has highlighted worrying security risks in NAS. Architectures found through automated searches can hide vulnerabilities that human designers would usually avoid.

For example, one study revealed that NAS-generated networks can be more vulnerable to adversarial attacks than hand-crafted models. While NAS focuses on maximizing accuracy with clean data, it often ignores robustness against subtle perturbations. This means attackers could craft inputs that look normal but trick the model into making wrong predictions.

Backdoor attacks are another serious concern. If attackers manipulate the training data used in NAS, they could push the search toward architectures with hidden weaknesses. These backdoors stay dormant under normal conditions but activate when triggered by specific inputs.

The field is now taking steps to address these issues. Researchers are exploring robust NAS methods that include adversarial training or robustness metrics in the search process. Yet, fully understanding and mitigating these security risks will take more work. Until then, deploying NAS in critical systems requires caution.

Reproducibility Challenges

Despite benchmark datasets, reproducibility remains problematic in NAS research. Subtle implementation details significantly impact results, yet papers often omit these details due to space constraints.

Random seeds affect outcomes more than typically acknowledged. The same NAS algorithm with different random initializations can discover architectures with performance varying by several percentage points. Published results often report the best run from multiple trials, creating an optimistic bias.

Hyperparameters for the NAS algorithm itself—learning rates for architecture parameters, temperature in evolutionary selection, exploration bonuses in RL—require careful tuning but rarely receive detailed documentation. Reproducing published results without access to the original code becomes difficult or impossible.

The community is addressing this through better code sharing practices and standardized evaluation protocols. Many researchers now publish full implementations alongside papers. Benchmark datasets provide controlled environments where reproducibility is guaranteed. These practices help, but NAS reproducibility still lags behind other ML areas.

Future Trends in Neural Architecture Search

The field continues evolving rapidly, with several promising directions emerging.

Joint NAS and Hyperparameter Optimization

Current NAS methods usually keep hyperparameters—like learning rate, batch size, and augmentation strategies—fixed during the architecture search. This can cause a mismatch: the architecture is tested with hyperparameters that might not suit it.

Joint optimization methods solve this by searching for both architecture and hyperparameters at the same time. This approach recognizes that what works for one architecture might fail for another. Early studies show that joint optimization often finds better architecture-hyperparameter pairs than sequential methods.

The main challenge is the bigger search space. Adding hyperparameters makes the search more complex and costly. To handle this, researchers use smart strategies. Multi-fidelity optimization, for example, gives more resources to promising configurations. Transfer learning can also help by sharing knowledge across the combined search space.

Zero-Cost Methods and Training-Free Search

Zero-cost proxies are opening up one of the most exciting efficiency frontiers in NAS. If we can reliably rank architectures without any training, the whole process becomes almost instant. Instead of waiting weeks, researchers could evaluate thousands of models in just minutes.

Right now, these methods work well in specific scenarios. However, they still struggle across diverse tasks and search spaces. Because of this, their reliability is inconsistent. The community is actively exploring why certain proxies succeed in some cases and fail in others. At the same time, researchers are looking for ways to design metrics that remain stable across broader settings.

This is where theory really matters. Most zero-cost proxies were discovered through experimentation, not solid theoretical grounding. As a result, we don’t fully understand why they work. Building strong theoretical foundations would help identify which initialization properties truly predict trainability and final performance. In turn, this would lead to more dependable proxy designs.

Meanwhile, ensemble approaches are showing strong potential. By combining multiple zero-cost proxies with learned weights, these methods consistently outperform any single metric. Even more promising, meta-learning techniques can train these proxy ensembles on past NAS tasks and then transfer them to new searches. The result is better generalization and more reliable performance across different problems.

AutoML Meets Large Language Models

The rise of large language models is opening fresh doors for Neural Architecture Search. These models already carry massive knowledge about neural network design. They learn it from research papers, codebases, and deep technical discussions. That makes them surprisingly good design partners.

One exciting idea is prompt-based NAS. Here, you simply ask an LLM to design a network using natural language. For example, you might say, “Create a fast convolutional network for mobile image classification, where speed matters more than accuracy.” In response, the model generates a clear architecture description. You can then build it, train it, and test it in practice.

Beyond generation, LLMs can also speed up the search itself. Instead of exploring blindly, they analyze past architectures and performance results. Based on that context, they suggest promising areas to explore next. As a result, the search becomes smarter. This creates a human-in-the-loop workflow where automated search, LLM intuition, and human expertise work together.

Evolutionary NAS also benefits strongly from LLM guidance. Traditional evolution relies on random mutations, which can be inefficient. In contrast, an LLM proposes meaningful architectural changes based on design principles. These semanitic mutations often lead to better models with far fewer evaluations.

Looking ahead, the link between NAS and LLMs will only grow stronger. As these models improve, the line between fully automated design and AI-assisted design will fade. Ultimately, humans and machines may collaborate seamlessly to create neural architectures faster, smarter, and with more creativity than ever before.

Conclusion

Neural Architecture Search represents a major shift in how machine learning models are designed. Instead of relying on intuition, NAS treats architecture design as an optimization problem. This approach has made advanced model development more accessible and has accelerated innovation across many domains.

The progress has been dramatic. Early NAS methods required thousands of GPU days, making them impractical for most researchers. Today, efficient and zero-cost techniques can produce useful results in minutes. Because of this, automated architecture discovery is no longer limited to large organizations. Individual researchers and small teams can now use NAS effectively.

Several key lessons stand out. A well-designed search space is just as important as the search algorithm itself. Efficiency techniques like weight sharing and differentiable search are critical for real-world use. In addition, benchmarks and reproducible evaluations are essential for measuring meaningful progress.

For practitioners, a practical mindset matters. Start with established methods such as DARTS or one-shot NAS. Validate your setup on benchmark datasets before applying it to custom tasks. Choose methods that match your compute budget, and always retrain final architectures from scratch before drawing conclusions.

Looking ahead, NAS will continue to evolve. Its integration with hyperparameter optimization, improvements in zero-cost proxies, and growing focus on hardware-aware design will make automated model discovery even more powerful and practical.

Neural architecture search does not replace human expertise. Instead, it enhances it. By automating exploration and revealing non-obvious design patterns, NAS allows researchers to focus on higher-level decisions—what problems to solve and how to deploy solutions responsibly.